BY: MICHAEL ROMANO

After conducting a survey of local residents, the coalition finally settled upon a unique strategy: Build a soccer field for the kids.

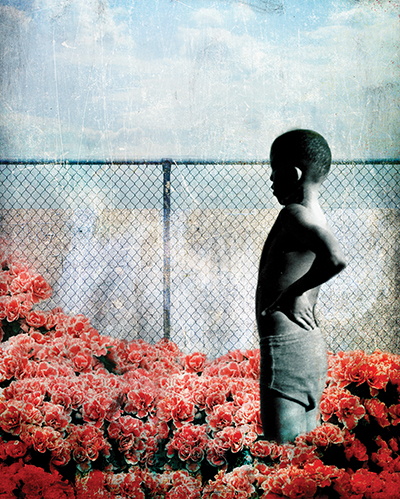

To most observers, transforming a garbage-strewn, weed-covered lot into a soccer field doesn't necessarily fit the typical formula for addressing violence and anti-social behavior among teens. Yet this simple, slightly unconventional approach to the neighborhood's deep-seated problems has had a significant and enduring impact, creating a healthy oasis where youths gather every day to channel their energy rather than their anger.

"Building a new soccer field to prevent youth violence is definitely not a traditional approach," acknowledges Doug Baxter, the violence-prevention coordinator for CHI Franciscan Health in Tacoma, a co-sponsor of the soccer-field initiative and a wide array of other community programs serving hundreds of families across the region. "When most people think of violence prevention among youth, they think of outreach to members of street gangs, anti-bullying programs in schools or job programs for teens.

"But these kinds of programs are designed to deal with an existing problem — they represent an intervention after the fact. The creation of this soccer field, on the other hand, is designed to prevent the problem from happening in the first place by identifying issues and possible solutions 'upstream' rather than downstream, after they have already occurred."

Indeed, the soccer field — once an unused lot behind the community center in Westway, a neighborhood where Habitat for Humanity has been busy building or renovating homes — embodies several of the important protective factors that experts say help shield youths from bad outcomes. It provides kids with a safe place for healthy recreation, helps them develop skills around cooperation and teamwork and exposes them to positive, caring adults, among other affirmative outcomes.

SOCCER FIELD SUCCESS

The results have been dramatic for a project whose intent was to reduce suspensions and expulsions for violent behavior among neighborhood youth, a contributing factor to a wide array of socioeconomic issues. Since the soccer field opened about three and a half years ago, the number of expulsions and suspensions has decreased significantly each year. In the 2014-2015 school year, expulsions and suspensions dropped by 43 percent from a baseline number three years earlier — an indication that the broad approach to healthy living, embodied in part by a modest soccer field, is having an impact that may last for many years.

"We think it's been a huge success," Baxter says. "The response has been greater than we ever expected."

This upstream approach identifies at-risk youth and provides strategies to mitigate the problem long before it becomes widespread. It represents the bedrock principle of a national violence prevention campaign launched in 2008 by Englewood, Colo.-based Catholic Health Initiatives, which operates Tacoma-based CHI Franciscan Health.

With its mission to create healthier communities, CHI has focused on aspects of violence prevention since its formation in 1996, when it created an in-house grant program called the Mission and Ministry Fund to support local efforts to improve communities' overall well-being. It turned out that many proposals for grants large and small involved some aspect of violence prevention — a seemingly inevitable outcome, considering that hospital emergency departments see the direct result of violence in their communities almost every day.

"At one point, we found that about half of the programs CHI was supporting through the Mission and Ministry Fund involved some aspect of violence," said Kevin E. Lofton, CHI's CEO and the champion of the violence-prevention project. "It ranged from gang violence and youth violence to elder abuse and domestic violence. So we decided it might be more effective to truly focus our efforts on a national effort to address all of these areas of violence. So we intensified our efforts — and our financial investment — on identifying the best projects and replicating them."

When CHI was formed, the vision statement identified three key areas of emphasis: Promoting healthy communities; expanding the expression of the health care ministry by growing and evolving to meet emerging needs and opportunities; and using the organization's size and scope to create systemic change, especially by being a voice and an advocate for persons who are poor and vulnerable. Those three areas converged as something of a call to address the growing epidemic of violence.

"In health care, our focus has always been on trying to deal with illness," says Sr. Peggy Martin, OP, JCL, CHI's senior vice president for sponsorship and governance. "Working to prevent violence is a different way of dealing with this vital issue — we're focused on bringing about wellness and providing for the health of entire populations — not just the patients who come into our facilities."

'UNITED AGAINST VIOLENCE'

Since it was unveiled in 2008, CHI's "United Against Violence" campaign — the only such nationwide program of its kind created by a health system — has grown steadily across the far-reaching footprint of the organization, which operates 103 hospitals and hundreds of other health care facilities in 19 states.

CHI's Mission and Ministry Fund has provided more than $15 million in support to the program, which has blossomed to include 43 separate violence-prevention programs in every CHI community. Each works in partnership with community, civic and governmental groups on programs designed to meet the particular needs of the local population, whether the focus is on domestic violence or child abuse, bullying or human trafficking.

"We've always been focused on violence prevention — it's part of our DNA," says Colleen Scanlon, CHI's senior vice president and chief advocacy officer. "But we felt we needed a broader, more intense effort focused on preventing violence, knowing that we would simultaneously continue to respond to the victims of violence in our communities.

"We decided to put more structure around it and develop a concrete plan to engage the entire CHI community across the country. Now, after lots of work with community partners and stakeholders, we can say that we have violence prevention programs in place in each of the many communities served by CHI."

Diane Jones, CHI's vice president for healthy communities, adds, "We're not finished — not by any stretch of the imagination. We've made significant progress in many of our communities, but we are in it — and they are in it — for the long term. This kind of work takes time to be truly successful — and sustainable."

VAST PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

Each year, more than 56,000 deaths by violence occur in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which describes the issue as a "public health problem of vast proportions."

Highlighting the urgent need for upstream programs, the CDC's National Center for Injury Prevention and Control adds this context: "Violence erodes the very fabric of our communities. Fear associated with violence can cause people to spend less time outdoors being active, socializing with others and investing in the community. Violence also lowers our productivity, disrupting important public and social services and decreasing the value of our homes and businesses."

Other disturbing statistics:

- There were about 702,000 victims of child abuse and neglect reported to child protective services in 2014, according to the CDC. The youngest children are the most vulnerable, with about 27 percent of reported victims being under the age of 3, the federal agency said.

- Every day, 13 young people between the ages of 10 and 24 are killed in this country, making homicide the third leading cause of death in this age group, according to the CDC.

- 1 in 5 women and nearly 1 in 59 men has experienced an attempted or completed rape in their lifetime, the CDC says.

- Every nine seconds in the U.S., a woman is assaulted or beaten, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, which also says that 1 in 3 women — and 1 in 4 men — has been the victim of some form of physical violence by an intimate partner within their lifetime. On average, the organization adds, nearly 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner in this country. In a full year, this equates to more than 10 million women and men.

Says Sr. Martin: "Violence is very clearly a problem of epidemic proportion in this country. It's stunning how many lives are affected — and how many lives are destroyed. When CHI started this work, our goal was that eventually every local entity sponsored by the organization would be involved in violence prevention in some way. We've had a wonderful connection between the CHI health entity and the community it serves. We consider this the foundation of our long-term goals in preventing and eradicating violence."

To Lofton, the focus on violence prevention is part of CHI's systemic effort to not only improve the overall health of the communities it serves, but also to deal with another vexing problem: the ever-escalating cost of health care.

"When you look at the overall picture," Lofton says, "so much of the high cost of health care is associated with treating people in emergency departments. And, at the same time, consider how much of that cost can be eliminated when we reduce violence?"

In fact, according to the CDC, violence-related death and injury cost the U.S. in excess of $107 billion in medical care and lost productivity annually.

COMMUNITYWIDE APPROACH

CHI's violence prevention model, which was developed in conjunction with the Oakland, Calif.-based Prevention Institute, relies on a public health approach that emphasizes communitywide solutions to problems of violence — or primary prevention. The most effective strategies, in fact, focus on dealing with entire populations, a policy that aligns perfectly with the goal of health systems such as CHI to treat illness more effectively by concentrating on populations and developing an approach rooted in public health and prevention.

"When we started this, we weren't experts in violence prevention," Jones notes. "We formed a strong partnership with the Prevention Institute to work on an evidence-based primary prevention model — the kind of a model that has worked so effectively over the years. When you look at major improvements in community health and health status over the last 50 years or so, it hasn't so much been clinical interventions as public-health interventions that have made a huge difference in issues such as seat belts, smoking, car seats for children and dangers around lead paint in homes."

Jones says there are four principle reasons that violence is a public health issue: It is a leading cause of disability and premature death; it represents a significant health disparity that disproportionately affects young people and people of color; it increases the risk of poor health outcomes through adverse childhood experiences (ACES); and the fact that most violence is preventable, for it is a learned behavior that can be addressed through collaboration, coordinated communication efforts and an emphasis on primary prevention.

Since receiving an initial grant of $14,700 in 2009, the first year in which violence prevention funding was available through the Mission and Ministry Fund, Tacoma's wide-ranging program has received three additional CHI grants that will help to underwrite community initiatives through 2017. The most recent grant, awarded in 2014, amounted to almost $470,000. In addition to providing considerable direct financial support to community organizations, CHI Franciscan Health has sponsored dozens of in-school programs while expanding the scope of its work to middle schools across the Washington communities of Key Peninsula, Des Moines and Federal Way, where more than 22,000 youths are involved in some aspect of the violence prevention program.

SUCCESSFUL STRATEGIES

In fact, CHI Franciscan and a broad coalition of partners in the community have developed about a dozen strategies in recent years to mitigate violence. These include:

- Working with Westway feeder schools on expanded Second Step curricula. Second Step is a program designed to reduce aggressive behavior in children and adolescents by increasing their social competence skills. It includes lessons for students through the eighth grade in areas such as empathy, problem-solving skills and anger management techniques.

- Creating a community garden at a local elementary school to boost parental involvement.

- Helping the community successfully advocate for safe walking and biking trails out of the neighborhood to mass transit, shopping and local secondary schools.

- Providing multiple training programs to local educators and nonprofit staff around adverse childhood experiences.

- Offering classes in English as a Second Language for parents in the Westway neighborhood.

"No one strategy is entirely responsible," Baxter says. "It's the variety, depth and breadth of the strategies that have made these efforts collectively successful."

Still, back in 2012, with the program largely in the developmental stage, it took some time for the idea of a simple soccer field to take hold among the coalition of groups working in and around Federal Way, a Tacoma suburb along Interstate 5 that is pockmarked by economically depressed neighborhoods wracked by poverty and high crime rates.

The idea of the soccer field, Baxter says, bubbled up after a neighborhood survey demonstrated that a place for kids to play soccer was a No. 1 priority around the Westway neighborhood, where the coalition was coordinating its efforts. The field was built with about $50,000 in funding from several sources, including the Franciscan Foundation, and is now self-sustaining, with a local homeowners' association maintaining the property. Today, hundreds of elementary school children have free access to soccer leagues provided by the Boys & Girls Club.

"With this soccer field, we've helped to build community resilience," says Baxter.

NORMAL AND NOT

In Nebraska City, Nebraska, a town of about 7,300 in the easternmost part of the state along the Missouri River, CHI Health St. Mary's and a broad-based community coalition have worked since 2009 to reduce reports of bullying and assaults among youths ages 10 to 17. Alarmed by the increase in the number of juvenile arrests in recent years, the coalition — the county attorney's office, schools, law-enforcement agencies and the local tourism office, among others — created an expansive community awareness effort that included billboards, yard signs, wrist bands, note cards and banners. The tag line: "Anger is Normal. Violence is Not."

"We wanted the kids to hear the message that it's OK to get upset about some things — but the important thing is how you deal with that when it happens," says Traci Reuter, who directs the hospital's Healthy Communities efforts and also serves as foundation coordinator.

In addition, the Nebraska City coalition — like its counterparts in Tacoma — has relied heavily on Second Step, taught year-round to approximately 1,800 children in grades K-8 in four school districts. Meantime, financial support from CHI has underwritten a number of new extracurricular activities for school children in Nebraska City and surrounding Otoe County, fostering a growing participation by youths in positive activities sponsored by supportive adults.

The coalition's goal was to reduce reports of bullying and assaults by 10 percent by 2014 and to decrease the percentage by as much as 20 percent by 2020. By 2014, however, reports of physical aggression among youths between the ages of 10-17 fell by 63 percent according to the Nebraska Risk and Protective Factor Student Survey. The survey also reported that juvenile arrests for assault — a principal motivator of the coalition from the start — fell by 51 percent, and incidents of school violence dropped by 73 percent.

The violence prevention effort extends well past Otoe County schools. Indeed, the walls of some local taverns now are adorned with the same placards found in elementary schools: "Anger is Normal. Violence is Not."

"The coalition has done a good job of increasing community awareness and changing the norms of what is acceptable behavior," Reuter says. "Before we started this work, many residents — even in such a small community as this one — were not really aware that youth violence and bullying existed in our community unless it personally affected them or someone they knew.

"We're all very excited to see how the culture here will evolve over the next 10 or 20 years."

For Sr. Martin, the key to the future is sustainability — or survivability, which also means shared accountability and collective leadership among the many and diverse programs. Although CHI's grants have laid a national foundation for an effective program, the organization, which cannot support every program indefinitely, is working with local leaders and other stakeholders to identify other potential sources of funding in the future.

"Violence prevention is definitely an ongoing process — and these programs will always need some help financially," says Sr. Martin. "So, the idea of sustainability is the key. We will continue to work with all of the programs to help them succeed. We certainly need outside help to support these for the long term."

Violence prevention programs like Nebraska City's — big and small, well-developed and just beginning — are now helping thousands of individuals across the country. Among them:

- In Omaha, CHI Health, Creighton University and the Women's Center for Advancement have teamed up to reduce intimate partner violence and sexual assault among college students. A 2012 survey of Creighton students found that about 16 percent experienced some form of partner violence, while almost 9 percent were victims of sexual assault. Since the 2015 fall semester, more than 2,575 students — about half of the total undergraduate population — have heard violence prevention messages as part of the program sponsored by the coalition. In that same period, about 185 students and 70 staff members have been certified via "Green Dot," a program that teaches "active-bystander skills" to provide tools to help individuals safely intervene in potential acts of violence. In all, more than 600 students have been trained in the program during the last three years. The coalition's goal: Reduce incidents of sexual assault and intimate partner violence by 20 percent by 2020.

- In Columbus, Ohio, the Dominican Sisters of Peace and the Franklin County Coalition have focused on the pervasive violence affecting a single trailer park community that serves as home to more than 250 families — about 90 percent of which have experienced some form of violence in recent years. That includes gun and gang violence, domestic violence and bullying. The coalition, working with scores of families, created a curriculum of positive programs that elevated leadership skills, self-esteem, health and wellness for members of these low-income families. Workshops included the development of positive police-community relations and seminars on immigration rights. Within three years of the program's debut, the coalition says, about 80 percent of residents noted a reduction in experiencing violence, including gang and gun violence. Youth bullying has been reduced by 72 percent, leaders say.

- In Roseburg, Oregon, the Mercy Foundation (part of CHI Mercy Health) and the Douglas County Community Coalition have worked with a coalition of about 30 individuals and groups to significantly decrease child abuse and neglect. The foundation and the coalition work directly with youth and deliver their educational messages at local schools. When the group began its work in 2010, the goal was to reduce cases of confirmed child abuse by 5 percent in five years. In fact, confirmed cases have decreased by 24 percent over that five-year span.

"We can now very happily say that we have a partnership — a real collaboration — in at least one community in every market we serve, to address violence," says Scanlon. "It's rewarding to follow a journey that is so intrinsic to the culture and purpose of CHI. Since we started this, we know that, externally, others are recognizing that a commitment to violence prevention should be a key part of the work of any health system if we are really about building healthy communities."

GOING UPSTREAM

As part of its upstream approach to primary prevention, CHI recognizes violence as a treatable, curable public health epidemic instigated by a whole host of risk factors that contribute to long-term problems, including violence, drug use and alcoholism.

Primary prevention is aptly described by the Prevention Institute in a book titled, Prevention is Primary: Strategies for Community Well-Being. The tale goes like this:

"While walking along the banks of a river, a passerby notices that someone in the water is drowning," one passage reads. "After pulling the person ashore, the rescuer notices another person in the river in need of help. Before long, the river is filled with drowning people, and more rescuers are required to assist the initial rescuer. Unfortunately, some people are not saved, and some victims fall back into the river after they have been pulled ashore. At this time, one of the rescuers starts walking upstream.

"'Where are you going?' the other rescuers ask, disconcerted.

"'I'm going upstream to see why so many people keep falling into the river.'

"As it turns out, the bridge leading across the river upstream has a hole through which people are falling. The upstream rescuer realizes that fixing the hole in the bridge will prevent many people from ever falling into the river in the first place."

As it focuses on primary prevention, CHI consistently has emphasized one integral strategy over almost any other factor in its focus on violence prevention: Community collaboration.

"We see ourselves as a partner in communities with many, many stakeholders who share similar interests," says Scanlon. "It's out of a rich community discourse on key issues that the focus and activities around violence prevention emerge. It's always been the members of the community who decide what they think are the most pressing issues — or the area of violence that they want to focus on. We want to work closely with our communities to help identify, develop, design and implement violence-prevention efforts."

Says Lofton: "As an organization, CHI has been blessed with wonderful, caring people who work across the ministry. So many have given so much to our efforts to reduce or eliminate violence in our communities. We've had some great success, but there's a lot more work to do.

"Fortunately, the people who work here -- along with the hundreds of community leaders and volunteers who have joined them on this journey -- truly believe in what we're doing and have poured their hearts into it.

"That's become a true hallmark of this effort."

MICHAEL ROMANO is national director, media relations, at Catholic Health Initiatives, Englewood, Colorado.