BY: DOUG LIPMAN, M.A.

Imagine you are choosing a nursing home for an aging relative. You have narrowed your choice to two that offer similar programs and meet your basic requirements. One of them describes itself this way:

We provide the highest quality health care. Our residents benefit from both personal attention and professional expertise in the state-of-the-art surroundings of our facility. We offer a library, classes, and, of course, the latest technology, which helps our highly trained staff monitor our residents' health needs and well-being and offer care with a personal touch.

Suppose that the other place has an equivalent description, but also offers this story by a care provider:

During the early hours of one morning, I attended to the needs of a terminally ill gentleman and mentioned to him that it had started to snow. In a very weak voice he said, "I would so like to touch the snow once more."

The snow continued to fall during the night. At 4:30 a.m., I took a tray outside, collected a mound of snow and took it to his room. He was awake, and when I told him I had brought him snow to touch, he smiled. I covered the bed linen and placed the tray on his bed. He reached into the snow, picked up a handful and slowly rubbed it across his face, neck, forehead and lips. He then closed his hand and held the snow until it melted.

I stood and watched; there was such a sense of peace about him. I felt very happy that I was able to fulfill his wish.

Less than two days later, he passed away. I believe that in the future, whenever it snows, the memory of him holding snow in his hand will come to me.1

Which nursing home would you prefer to live in? Which one do you feel most confident would offer "care with a personal touch"?

If you chose the second one, you have experienced the power of stories.

CONCEPT-TALK VS. STORY-TALK

The first nursing home description relies entirely on what I call "concept-talk," the abstract, bullet-point type of talk that businesses have favored for generations, using important, targeted phrases like these to make its point:

"personal attention"

"professional expertise"

"the latest technology"

"care with a personal touch"

Such concept-talk is excellent at conveying abstractions clearly and quickly. But abstraction requires leaving some things out, especially the sensory, the individual (the specific actions and reactions that make up moment-to-moment human experience) and the contextual (under what circumstances is the attention at the nursing home "personal"? What happens when "personal" seems to conflict with "professional"? How does staff negotiate such judgment calls?)

In short, the efficiency and clarity of concept-talk tends to leave out the human dimension, a critical component for communicating mission in health care. Concept-talk can't do the job alone. You need stories on your side both to inspire and to transform your organization's mission and value statements into living documents.

Stories will convey your organization's spiritual dimension; they will show the way people are treated with compassion and dignity in everyday encounters — in short, they will demonstrate the power of what drives Catholic health care.

When you are talking about what you do, what you value and what you believe, you need to include stories.

THE ESSENCE OF STORY

The essence of story-talk is the particular: At one moment, in one place, one person took one action. That's how life happens — in specific moments and actions. Story, therefore, is the language of living experience. It begins by enticing your listeners or readers to imagine the concrete events of the story.

For example, in the story above, think of the tray of snow. In your mind, what color was the tray? What material was it made of? How large was it?

Some people might imagine a cafeteria tray. Others might imagine a detachable bed tray — still others, a medicine tray or even a surgical tray. Each reader imagines the story in unique ways, using a unique, personal collection of experiences and predilections.

Why is this imagination-based process of story-listening important? Because it underlies some of the vital properties of stories.

Stories invite participation. Listeners or readers are actively involved in the creation of images.

One story can stimulate an infinite variety of mental images, each arising from a particular listener's background and preferences. Further, each listener creates a unique version of the story's meaning that is compatible with his or her mental framework.

Stories are made of images, not words. The important story is not the one on the page, but the one that lives in the mind of a reader or listener.

As listeners or readers, we get a chance to view our world with empathy for those we may never meet, because stories show us events from the point of view of particular characters. For example, we mentally experience the touch of snow by the "terminally ill gentleman." We experience the caregiver's happiness at seeing the gentleman's sense of peace.

So the power of using stories in mission work is two-fold:

- Stories allow us to make our mission come alive in others' minds

- By its very nature, listening to a story tends to encourage empathy and personal involvement

CONNECTING STORIES TO VALUES

If stories are so useful, which stories are most important to tell? When I work with groups of leaders, I ask them each to think of a current, urgent problem that their institution faces. Let's suppose it is culture conflict stemming from a new acquisition of another hospital.

Then I would ask them, "What is a value, like cooperation or compassion or constancy of purpose, which you believe will play a key role in helping navigate to the solution?"

One leader might decide that putting the good of the whole institution above individual or departmental concerns could be a key to solving the culture conflict.

Then I would ask that leader, "What happened in your life to teach you the importance of putting the larger community above individuals in certain circumstances? Think of experiences during any point in your life, from early childhood to last week."

If I have made it safe enough, the leaders will begin recalling experiences about the values they chose. I will encourage everyone to tell them to me or to a partner. I will say, "Tell whatever experiences come to mind, whether they seem related to this topic or not." (Many incidents that don't seem relevant at first turn out to be highly relevant once told in their entirety.)

In time, I'll ask someone to choose one of those experiences for telling to people in the course of solving the problem. Here is an example:

As a teen, I fought to be elected president of a club. The opposing candidate was my archrival. Our intense rivalry nearly caused a rift among the members until my opponent volunteered to cede the election, for the good of the club. This left me admiring my opponent.

I will then help the leader shape the story to include all the incidents, and only those incidents, required to help listeners experience the chosen value in action: putting the good of a whole group above individuals.

Now the leader has a "value story" to tell that makes the value concrete and human. The leader will have a seed to plant in the minds of others, to help them, too, experience for themselves the value in action.

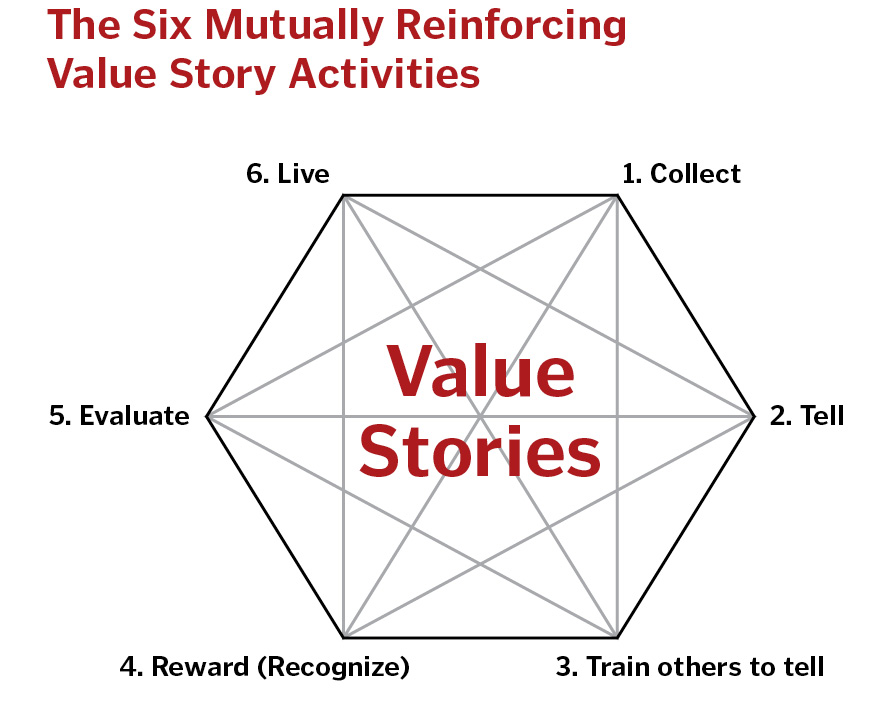

THE SIX MUTUALLY REINFORCING VALUE STORY ACTIONS

At this point, you know what a value story is, as well as why it can be so influential. Now you can learn how to integrate the telling of value stories into the life of your organization.

There are six key actions that create a value-story organization. Each of these actions reinforces the other. In fact, once you've established all six actions as standard practices in your institution, they can become nearly self-sustaining.

There are six key actions that create a value-story organization. Each of these actions reinforces the other. In fact, once you've established all six actions as standard practices in your institution, they can become nearly self-sustaining.

Establishing any one of the six practices without the others, however, is difficult. At the start, you need to work on all six fronts nearly simultaneously.

Action 1: Collect Value Stories

Your executive team and senior managers need to go through a process similar to the one described above. They will each move from a current problem to a value important to solving it — and then to a personal experience story showing how the teller discovered the importance of the value.

But it doesn't stop there. To help transform the organization, you also need to collect the experience — stories of people at every level of your organization — managers, support staff, front-line staff (both medical and non-medical), health care providers, patients and their family members.

You want two kinds of stories: Those that demonstrate values in action and those that demonstrate the violation of values. The simplest way to collect them is to ask for them in ordinary conversation. For example, ask a patient or family member, "What was it like to be a patient here? Did anything especially good or bad happen during your stay?" Ask a fellow employee, "What's happened lately to make you proud of working here? What's happened lately that put you in a difficult position?"

You don't have to do the asking yourself. You can delegate the finding of stories to individual work groups, buildings, or departments. Or you can have contests for "value story of the month," etc.

Story-gathering tips:

Figure out a method for keeping track. Perhaps you keep an informal notebook where you jot down the date, the teller's name and key points about a story you heard. Perhaps you send an employee with a video camera to record the story you just heard.

Jot down possible values that each story might illustrate. If you do this as you collect the stories, it will be invaluable for later reference. Please note that any story can illustrate multiple values. The snow story, for example, could illustrate many ideas, ranging from "the smallest favors can have the greatest impact" to "patient needs can take many forms, and so can meeting them."

No list of the values conveyed by a particular story will be complete. But the exercise of creating such a list can make you aware of multiple situations in which a story might be appropriate later on.

Action 2: Tell the Stories Everywhere

Nothing can replace the power a story gains when told by one person to another in the context of a respectful relationship. You lend your personal outlook and authority to the stories you tell. In return, the best stories amplify the impact and authority of those who tell them.

Look for ways to include stories in all these situations:

- Speeches

- Supervision

- Informal conversation

- Publicity materials and ads

- Meetings

Meetings are particularly easy times for stories, because you can institute a policy of beginning each meeting with a story. If you already begin with prayer, the story can follow the prayer. If you begin with a meditation, the story can become part of it or even replace it.

It is easy to think, "I don't have time to tell stories in meetings or speeches; I have too much information I need to get across." The fallacy in that thinking lies in assuming all your information currently is both getting across and being retained.

In fact, the most important point of any speech or meeting deserves a boost from a story. Some people will understand fully from hearing your concept-talk. Others will understand fully only from hearing a story. Most people will understand best from a mix of both. Stories aid in understanding; the snow story, for example, clarifies one aspect of the broad concept of "personal attention."

If it is vital that your staff remember a point, tie it to a story. This principle applies doubly to external communications. Out in the world beyond your walls, you need the extra help that stories give for involving listeners as well as for communicating commandingly, clearly and memorably.

Human brains seem to be built with a special ability to remember stories. If you grew up in the U.S., for example, how many facts do you recall from elementary school about the life of George Washington? Still, I bet you can tell the cherry tree "I cannot tell a lie" story.

Action 3: Train Others

If you just say, "Tell stories!" without demonstrating, you may very well get behavior you don't want, ranging from irrelevant jokes to inappropriately long tales.

However, if you are collecting stories and telling them yourself at meetings and elsewhere, you already have begun training others. You have helped them discover their own stories, and you have modeled effective storytelling behavior.

After you have spent, say, six months telling a story at every monthly meeting, start signing up others to tell "the lead story" at subsequent meetings. This will both give them a chance to practice telling and motivate them to search for stories to tell.

When others tell a story — especially the first few times — be sure to offer a few words of appreciation. Even if the story had glaring faults, find a few of its strengths to mention: What was good about the story itself? About the way it was told? About its effect on you?

When you train people to tell stories, don't overlook the special needs of those speaking to the public, whether in ads, informational videos for your website or as expert commentators about matters of public interest. These people are the most public face of your organization, so equipping them with great stories and good storytelling skills will pay off many times over.

Action 4: Reward (Recognize) the Stories

Because stories are important to furthering your mission, it is important to recognize those who are engaging in this vital behavior. Even more importantly, you want to recognize those who are living the stories that embody your core values. You can do both at once by recognizing and rewarding value-oriented stories within your organization.

Try some or all of the following:

- Post written and/or recorded stories on your website and intranet

- Feature them in meetings, newsletters, ads, corporate reports, speeches and even memos

- Post them in your physical plant on posters, bulletin boards, in elevators, even printed onto cafeteria placemats

- Have a "story of the week" or "story of the month" award for your whole institution or for parts of it (departments, etc.), and display the winning stories prominently

- Create a "wall of values," featuring one (or all) of your core values, surrounded by written stories collected in your institution that illustrate them

- Reward and recognize those who contribute the stories and those who are featured in the stories by including their photos next to the written or recorded versions of their stories

- Give each person "caught doing something right" in a story a framed copy of the story, signed by you

- Have a handful of people tell their pre-selected value stories at celebrations, staff parties, etc.

- Create designations such as "story hero" and "story finder" and post lists of those who have been featured in or contributed usable value stories

- Have a senior manager visit each such story hero and thank her or him2

Action 5: Evaluate the Stories

Every project as important or as far-reaching as integrating value stories into your organization needs to be evaluated. Is it effective? Is it complete?

Track your noticed successes. Log them for later review. Collect stories of story successes — stories of how a story had a positive impact on a particular person or situation.

Notice any overall effects on attitudes. Are employees more motivated and more willing to cope with difficulties? Has their morale improved? Has the tenor of break-room conversation changed at all? Expect such results to appear only after many months, but notice them if they do appear.

Most of your evaluation for something as complex as stories will need to be qualitative. Nonetheless, you might notice how your quantitative measures proceed: Are you noticing fewer patient complaints, smaller staff turnover, more new patients from targeted neighborhoods? It may be difficult to determine how much each of your various efforts contributes to improvements in those measures, but when these measures are combined with qualitative and anecdotal results, you will be able to estimate the effectiveness of your value story program.

Evaluate your growing collection of stories about the values being lived in your organization. Are there stories that are missing? In particular, do you lack stories for a particular category, such as:

Values. What values do you espouse that aren't yet well represented by stories?

Roles. Are there too few stories from people in certain roles in your organization, such as physicians or maintenance workers or families of patients?

Demographics. Are there too few stories from, for instance, a particular gender, race, income group or age group? Are there stories from able-bodied employees and patients but too few from those with disabilities?

Contexts. Are there too few stories from certain departments or locations? Are there plenty of stories from inpatients but too few from outpatients?

For each lack you notice, try to determine: Do you lack those stories because you haven't found the stories that exist, or because certain values aren't being lived out by certain groups of people?

If the problem is that you haven't found the stories, what's the roadblock to finding them? Are you asking the wrong people? Requesting stories from employees may not yield many patient stories, for example.

Are you asking the wrong way? Requesting stories via memo may yield many fewer stories than asking in person. Further, different cultural groups may react differently to requests for personal stories and therefore need to be approached differently. Asking for written stories in English from speakers of other languages, too, may not produce as many stories as you would hear with in-person interviews assisted by translators.

If the stories don't seem to exist, this may mean that you're not living out some values that you espouse, or that you're not reaching certain populations, or that you're treating some populations in a way that they consider dismissive or disrespectful. In this case, your story collection becomes a diagnostic tool for identifying larger issues in your organization, and a future increase in certain stories can be a partial confirmation of having dealt successfully with such an issue.

Action 6: Live the Stories

This is both the most natural and the most difficult of the value story actions. Just as the living of your organization's values gives birth to stories, the stories themselves can stimulate the enacting of values in daily life.

Periodically, take stock of the value stories that seem most salient to you. Ask yourself, "Am I living up to these stories? Where could I act more like someone about whom these stories would be told?"

Once you succeed in implementing the six value-story actions, you will have made your organization's mission and value statements into living documents. You will have made your staff into living carriers of transformative stories. And you will have provided everyone in your sphere of influence with concrete ways to understand what sets your organization apart.

DOUG LIPMAN is a storytelling coach and author of four books, including the award-winning The Storytelling Coach: How to Listen, Praise, and Bring Out People's Best. He is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and holds an M.A. in writing from Hollins College, Roanoke, Va. In addition to onsite trainings in the applications of storytelling, he teaches online courses from his home office in Marshfield, Mass., where he also creates his free, monthly storytelling newsletter, "eTips from the Storytelling Coach."

Author's Note:

The author wishes to thank Linda Borodkin, Karen Dietz, Pam McGrath, Noa Baum and Jay O'Callahan for their help with the writing and editing of this article.

NOTES

- Sandra Greggo, "Whenever It Snows, The Memory of Him Comes to Me," in Sacred Stories, 1st ed., (reprinted with permission from Catholic Health Initiatives), 16. http://bur-ms-sm6-04a.medseek.com/websitefiles/chinational58533/body.cfm?id=38797.

- Ideas for recognizing employees and validating their stories, see: David Armstrong, Managing by Storying Around: A New Method of Leadership (New York: Doubleday, 1992); James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, Encouraging the Heart: A Leader's Guide to Rewarding and Recognizing Others (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003); Evelyn Clark, Around the Corporate Campfire: How Great Leaders Use Stories to Inspire Success (Sevierville, TN: Insight Publishing Company, 2004); Lori L. Silverman, Wake Me Up When the Data Is Over: How Organizations Use Stories to Drive Results (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006).

TEACHING OTHERS TO TELL STORIES

There are two primary tools for training others to tell stories. First, have them tell a story several times to willing listeners — I call that the Rachel Method. Second, have them appreciate stories told by others.

Rachel is a law professor who supervises law students who are arguing real cases for indigent clients.* The stakes are high, and the students are nervous. So Rachel trains her students to practice their opening statements as though they are stories. She schedules an hour or so and starts by asking the student to come into her office and give the opening statement, that is, tell the "story." Generally, the performance is terrible. But Rachel offers a few words of appreciation about whatever worked in the story, its performance or its effects.

Then she takes the student into the hallways and stops the first person to come by, perhaps a custodian. Rachel asks the custodian if he or she can listen to a three-minute story and just give a few appreciative comments at the end.

Rachel repeats the process for the entire hour. She says that by about the fifth retelling, the story starts to make sense. By the 10th telling, the student is giving the opening statement with confidence. By the 12th or 15th telling, the story is solid and impactful.

Create your own version of this method. Use it with a half-dozen managers, and assign them each to teach it to six more.

The second key tool for training others in storytelling is to have people practice appreciating the stories of others. Why? In order to give words of appreciation, people need to pay attention to what works in the stories they hear. That's the fastest way to learn what will work in your own stories.

Select employees to form "storytelling triads" to practice telling, listening and giving appreciation. Such storytelling training can strengthen a culture of appreciation and cooperation in your organization.

*Rachel's real name and institutional affiliation have been withheld at her request.

STORIES OF YOUR INSTITUTIONAL HISTORY

In addition to your personal value stories and stories that show values in action in your organization, it can be invaluable to collect the stories of your institutional history.

A particularly rich source of such stories is oral history interviews with founders and significant later leaders — and with those who remember them. Such interviews are worth recording. Consider audio or, even better, video recording. Consider, too, transcribing the results and then annotating stories that might be retellable, as well as the values and meanings such stories might be seen to contain.

If your hospital was founded by an order of women religious but is now run largely by lay people, for example, you can interview people who might know:

- What was special about the way the sisters behaved? What was sure to happen (or not to happen) when they were around?

- What stories did people tell about the sisters?

- When you arrived here, what did they tell you about how this place was run?