BY: JAMES HIGGINS, M.B.A.

New Needs Represent New Opportunities for Catholic Health Care

Mr. Higgins is CEO, Bon Secours New York Health System in Riverdale, N.Y., and Bon Secours St. Petersburg Health System in St. Petersburg, Fla. He is also thought leader for senior services, Bon Secours Health System, Inc., Marriottsville, Md.

As Catholic ministries, the call to the elderly is unquestionable. With the possible exception of the mentally challenged, there may be no group more poor or marginalized than the elderly members of the U.S. population. In 2005, over half of those over the age of 65 lived at or below 300 percent of the poverty line — an income level that places them at risk of need and public assistance — and nearly 40 percent of those over 75 years old live alone. Ironically, we are serving a generation that created a great industrial nation, fought in two World Wars and lived through the Great Depression, yet is often seen as a burden on society and a drain on the federal budget.

Our responsibility to provide a dignified and respectful death is likewise unquestionable. Only 15 percent of the 85 and older population die at home (40 percent die in a nursing home or other form of long-term care; another 30 percent die in a hospital), despite the fact that 85 percent of Americans say they would prefer to die at home regardless of their age.1

For people in the field of Catholic health care, these needs and challenges are good news. They present a tremendous opportunity for Catholic health care to lead the way, transforming institutional care to holistic person-centered care, helping seniors to maintain their independence by placing them in the least restrictive settings necessary, and advocating for the resources needed to effectively meet their wants and needs. Above all, Catholic health care needs to manage the care of seniors across a complicated health care delivery system in ways that offer choices, uphold dignity and ensure compassion and respect.

The Demographic Imperative

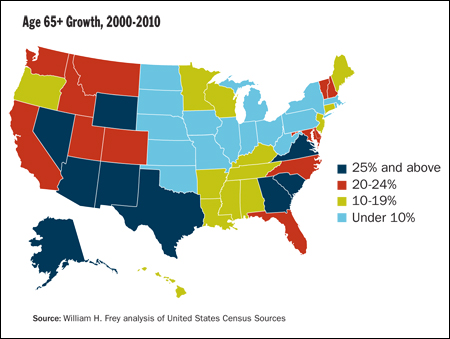

Each generation presents demographic challenges, albeit of different natures. For the baby boomers, their sheer numbers will produce unprecedented demand for health care services. On January 1, 2011, the date at which baby boomers begin to celebrate their 65th birthdays, 10,000 people will turn 65 every day — and this turnover will continue virtually every day for two decades.2 It is startling to compare the rate at which people will enter their senior years to just 10 years ago, when 6,000 people turned 65 every day.3 In other words, the baby boomer effect on the aggregate number of seniors will be roughly an additional 4,000 people per day.

By 2030, the number of people over the age of 65 will double to 70 million. As importantly, the number of seniors over the age of 100 will increase six-fold to 381,000. Additionally, more than 35 million seniors will be living with multiple chronic diseases, placing increasing burdens on the health care system, particularly hospitals and long-term care facilities. More individuals will be cared for at home or in another less restrictive setting, partly because of technological and pharmaceutical advances and partly because of the associated cost savings.

The boomers' children face challenges of their own. This generation, commonly referred to as the echo boom, faces the challenge of funding the care demanded by their baby boomer parents. For the echo boomers, a much smaller group, their lack of numbers present problems, especially as it relates to the beneficiary-to-worker ratios that determine the tax revenues on which most health care funding relies. According to the most recent estimates, the Social Security trust fund will be exhausted in 2037, just about the same time the echo boomers begin to reach retirement age.

Leaders should understand the profound impact these changes will have on our national health care system: on how we are reimbursed for care and where these services are delivered. It is critically important to constantly probe new and better ways of service to people in all of our settings, remembering that growth and innovation can be programmatic, person-centered and achieved through organizational culture change. Not all change requires a capital infusion. Longer term, however, senior services and home care must be "rightsized": reinvented and delivered in physical spaces dramatically different from what we have now.

Crafting a Vision of a Future Delivery System for Seniors

Leaders have an obligation to two basic tenets of senior care: 1) to provide a demonstrated level of quality care and an exceptional individual experience for those currently being cared for and 2) moving organizations to provide the same result for a new generation, in a new funding environment, in a very different way.

In a vision of the future, two basic sets of information are needed: 1) anecdotal or experiential learning and 2) assumptions about the future.

Anecdotal Information

In the 1970s, the frail-but-well elderly populated many nursing homes. For example, one New York City senior service organization displayed a picture of nursing home residents from the '70s and early '80s, dressed in dresses or in jackets and ties in front of a fireplace. They were frail but neither debilitated nor de-conditioned. They would sometimes frequent a local bar and some even slept in bunk beds. Since then, such facilities have cared for seniors who are more physically and mentally compromised. This trend, which has been incremental, is likely to continue, driven mostly by cost as seniors leave hospitals after shorter stays and, often, more physically compromised. This is an important assumption in planning for the future.

Here is an illustration: In 1975, when John was 65, he went to live in a nursing home. Although increasingly frail, he was independent, needing only minor help with his activities of daily living. At the nursing home, he played cards, dressed in a suit and often visited a local pub.

Today, John is 99 years old. He still lives in the same nursing home. But it is a very different place. The nursing home has undergone dramatic changes. For example, most of his fellow residents are now severely compromised in terms of mobility, medical condition and dependency. In 1975, these people would have been hospital patients rather than nursing home residents. John has congestive heart failure and takes 12 medications daily. Professional nurses, specialists and therapists — experts rarely seen in the nursing home when he entered almost three decades ago — provide his care.

Assumptions

In order to plan and prepare our ministries for the future, pictures, scenes and mental models must be based upon these assumptions; that is, on what we believe to be true, however improbable it might be.

At Bon Secours, we have used the following major assumptions to craft a vision of the future for seniors:

- Longevity will continue to increase (381,000 centenarians by 2030); people will live longer and better with chronic diseases.

- As the tax base in the United States decreases and the number of retired seniors increases, government funding will not be enough. Co-pay, deductibles and private pay will increase as payments to providers decrease.

- Pay for performance will eventually separate quality providers from non-quality providers, and funding will be redistributed.

- The availability of information and the Internet will further differentiate providers of care.

- The health care system, in order to save overall cost, will shift the location of service to the one that is the least costly and least restrictive. For example, seniors currently being cared for in hospitals will be cared for at home or in facilities outside hospitals, such as long-term care facilities.

- "Money follows the person" — capitated payments, bundled care and the like — will be the reimbursement systems of the future as government shifts the financial risk to providers.

- As people are asked to spend more of their own money on care, they will become significantly more discerning relative to demonstrated clinical outcomes, length of stay, quality of life issues and personal experience.

- Technology will play an increasingly important role in determining the location, cost and quality of care.

- Seniors' disabilities, chronic care onset or management can be delayed or prevented by a program of information, wellness and prevention.

- Many of the real issues that lead to a senior's entry into the health care system will continue to be non-medical (e.g., isolation, lack of transportation, home safety, etc.).

- A formal care management system will become imperative to provider survival, senior satisfaction and cost reduction.

Taking assumptions for the future and combining them with experiences in the past and present leads to a likely future scenario for the delivery of senior services. Whether from public or private sources, providers of care will be put at risk with a bundled or capitated payment based upon a variety of demographic factors. Providers will collaborate and control the location, type, timing — and thereby the cost — of care. To keep providers honest and to provide a safety net for the poor, government must play a role in assuring access and a level of demonstrated quality for the most vulnerable. Prevention, wellness and care management will be fully funded.

Baby boomers will be better off financially than the generation health care now serves. They will generally be more discerning consumers of health care, willing to spend more for demonstrated quality, for a dignified physical environment reflective of the special needs of the elderly, and for amenities that meet individual choices and address the frailty that comes inevitably with the aging process. This environment will be diametrically opposed to what is currently found in many long-term care facilities, assisted living, and home care programs. Currently providers "follow the money." The assumption that government currently funds what best drives quality, satisfies need, prevents unnecessary health care events, and keeps seniors in the least-restrictive and least-costly environment is simply not true.

If done right, attaching reimbursement to people instead of events could result in a spectacular senior service system that keeps seniors in the least costly setting longer, maximizes the use of technology, funds prevention and wellness and drives overall national costs lower. It will be in stark contrast to today's reactive, perverse and cost-based system, which drives costs higher.

Hospitals of the Future

To become a respectful, person-centered health care system, Catholic hospitals must change — adding senior-specific and senior-friendly programs that target older adults, as well as required gerontological training for staff. Life expectancy has increased from 50 years in 1900 to 78 years in 2003 and is expected to increase significantly as biotechnological advances and healthy-living standards increase. Due in part to this increased life expectancy, hospital admissions of seniors will increase significantly throughout the nation over the next few years: In 2004, 38 percent of hospital beds were filled by patients over 65 years old; by 2030, the percentage is expected to increase to 62 percent.4

Many studies clearly show the health of 85-year-olds admitted to a hospital is inversely proportional to the amount of time they spend there. There are several reasons for this. One is the lack of a geriatric, gerontological expertise that focuses on factors of aging as well and as much as the particular medical event that necessitated admission. Another is the understanding that confining frail elderly people to beds can lead to rapid de-conditioning and exacerbation of other chronic conditions.

These problems related to hospital care and the elderly have far-reaching implications in terms of quality, mission and business performance of Catholic hospitals and local systems that include long-term care facilities or provide home care. It is clear that these poor quality outcomes and length-of-stay issues are indicative of perverse incentives, as well as of the lack of advocacy-based care management and the absence of geriatric expertise as seniors move through health care systems.

Given the proportion of hospitalized older adults, the aging of the population and the increased risks of hospitalization to the health of older adults, it is imperative that Catholic health organizations incorporate geriatric expertise into practices. Several models designed to address issues for hospitalized older adults have been developed and evaluated. Such models range from a focus on staff development to creation of geriatric units to coordination of care.

Health care organizations will need to reorganize the hospital around the special needs of seniors and reconfigure part of the acute care delivery system into senior-specific systems. Hospitals will continue to discharge faster, and care related to exacerbation of chronic conditions will be treated more often in other settings, including long-term care facilities. Fewer seniors will be cared for in hospitals due to cost, care, treatment advances, and the availability of alternative settings, including retrofitted long-term care facilities, same-day surgery centers and outpatient clinics.

Traditional Senior Services of the Future

The nursing home of the future will more closely resemble the hospital of the present. Although most acute care procedures will continue to take place in the hospital or, more likely, a specialized care center, outpatient center, or physician office, long-term care facilities will be smaller and more medicalized. The current readmission rate to hospitals from long-term care facilities will be dramatically reduced by 24-hour physician coverage, on-site diagnostic capabilities and availability of more specialists and sub-specialists.

The sad fact is that readmissions to hospitals today come primarily from post-acute care facilities where on-call physicians create a revolving door for older patients — again due to a perverse fee-for-service payment system. Bundled payments will give providers incentive to treat the elderly in a more traditional, cost-effective setting. Combined with an infusion of geriatric-trained practitioners, this will create value both in terms of cost and quality.

Traditional assisted living programs, of which many flavors are already available, will provide specialized memory-loss programs, while others will capture a frail, debilitated population, including many people with chronic disabilities. Much of this population currently resides in long-term care facilities.

Independent living will explode into a model that offers safe physical spaces and a variety of wellness-related options, offered on an as-needed basis, such as medication reminders, care management coordination, housekeeping, transportation and lifelines.

Home-Based Services of the Future

Home care will transform the delivery system, and not only with medical monitoring through technology. Already the use of technology — along with the Internet and physician incentives for home visits — is allowing seniors to stay home longer or return home faster after a hospital or nursing home stay. Although infirmities and chronic conditions once treated in institutions are now often effectively cared for at home, the most significant home-care transformation in the near future will be to the smart house. (See related article in this issue, Homes Get Smarter, by Mark Crawford.)

Already drawing great interest from the private sector, smart homes will incorporate continuous, real-time monitoring devices to instantaneously detect changes — not only in the environment, but in the people who live in them. For instance, microphones will pick up changes in the voice that could indicate the onset of Parkinson's Disease. Sensors under the floor will detect shifts in balance. Beds will be wired to monitor weight fluctuations. Sensors will detect ice on a sidewalk and relay that information to a centralized monitoring station. Smart homes will also incorporate devices already on the market, such as remote-controlled lights and voice-activated electronics.

As wellness becomes a part of a national health care system, common sense and inexpensive technology will save costs and keep seniors happier and healthier longer. This will benefit not only seniors themselves, but also the national health care system as overall care-related costs are reduced. All in all, every component of health care will begin to meet seniors where they are or keep them in the more costly parts of our health care system for the shortest possible periods of time.

Care Management — The Linchpin

The health care system is often referred to as a maze. For many seniors, the complexity of the system is incomprehensible. Ironically, seniors usually interact with this complex system during their most vulnerable times — when they are sick or experiencing a health-related emergency. At a point when patients and their families are facing a major life challenge, perhaps the greatest of their lives, they must navigate and manage one of the most complex health care systems in the world.

Compounding the problem is the shift to outpatient and home-based care. Although these options allow people to spend more time in a comforting environment, they can place a heavy burden on patients and families. Patients are going home sicker, often without the resources needed to adequately address their physical needs or to manage the competing roles of parent, child, partner and employee. Where poor care management and coordination follows, the results can include more visits to emergency rooms, greater numbers of hospital admissions, longer hospital stays, high health care costs and a rise in numbers of life-threatening situations.

Because of the highly regulatory nature of the health care system, most of its complexity cannot simply be removed. But it can be made navigable for those it serves. Care management must be at the center of the future senior services delivery system. While it will not solve all the dilemmas of the modern health care system, it can address many of the barriers that prevent access to timely screening, follow-up and treatment and help to assure delivery of true person-centered, mission-driven, values-based care — right time, right place, right reason.

A care management program has the potential to:

- Follow people across the system, develop relationships with patients and families and advocate for their care.

- Fulfill CHA's Vision for U.S. Health Care and its core values of human dignity, concern for the poor and vulnerable, justice, common good, stewardship and pluralism.5

- Help large systems remove perverse reimbursement incentives, inappropriate transfers and so forth outside of the decision-making process.

- Help move health systems further away from institutional care and more toward the community (where health care in general is going anyway), based upon the assumption that most people would prefer to have care rendered in the least restrictive, most convenient location.

- Have the authority locally to help, transfer or advocate for all patients based upon a predefined process including business, mission and advocacy criteria.

While bundled payments will be an incentive for wellness, prevention and early intervention, the money, and therefore the setting, must not be controlled by the hospital. The care management program that will work for seniors will be independent of the components of a local system and be guided by advocacy, individuality and choice.

If payment is constructed properly, the provider system will do everything possible to keep covered individuals out of the health care system for the longest possible time. Properly constructed payments, for instance, will help prevent many chronic diseases and promote education and home safety, reducing the number of falls and the need for institutional care.

The new care management programs under a capitated or bundled payment system should extend to the at-risk frail vulnerable seniors not in the health care system. After all, health care should not be sick care. Prevention, wellness and early intervention through an advocacy-based care management program will serve us all. Currently almost three-fourths of every dollar spent on health care in the United States goes to people with at least one chronic disability.6 That money should be redirected to prevention-focused care management to the benefit of our country's economic well-being and those Catholic health care serves.

As Catholic health care providers advocate for and anticipate change, it is vital to remember that seniors are cared for in virtually all of the settings along the continuum, often accessing many in a short period of time. Traditionally, people categorize health care services by provider or payer type. When they think of health care services for seniors, they typically think of traditional senior service settings, such as long-term care facilities and home health agencies, or the de facto reimbursement source for seniors: Medicare. But seniors do not fit into such neat categories.

As Catholic health care professionals, we should embrace and support this vision of the future. It is respectful, compassionate, and dignified. Equally important, it is affordable.

Gerry Ibay, J.D,. contributed to this article. Mr. Ibay is strategic performance manager, Bon Secours New York Health System, Riverdale, N.Y.

NOTES

- Business Innovation Factory, "Nursing Home of the Future," www.businessinnovationfactory.com/nhf/files/Aging-in-America.pdf, page 29.

- Alliance for Aging Research, www.silverbook.org/browse.php?id=57.

- Alliance for Aging Research, Independence for Older Americans: An Investment for Our Nation's Future, (Washington, D.C.: Alliance for Aging Research, 1999), www.agingresearch.org/content/article/detail/695.

- FCG projections based on National Center for Health Statistics, National Hospital Discharge Survey 2004, May 2006.

- Catholic Health Association, Our Vision for U.S. Health Care, www.catholichealthcare.us/OurVision/principles/overview.htm.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm, (modified: November 20, 2008.)

HEALTH CARE REFORM AND THE ELDERLY

The health care system in the United States is about to go through profound and transformational change. The status quo is clearly unsustainable. The economic reality is that continuing health care market-basket increases that double or triple the Consumer Price Index, combined with a declining tax base as more people retire, will cause the system to implode. Even worse, knee-jerk political reaction to one part of the health care system — such as reduced provider payments — will inevitably lead to higher costs, poor quality outcomes, increased fragmentation, and a declining ability to adequately deliver care at the right time, for the right reason, and in the right place.

As the national debate focuses on details, provisions, special interests and components of the various bills, we are rapidly losing the big picture. We need to go back to the beginning. All Americans should be given health care that is of measurable quality and affordable — both individually and on a national basis. Sound impossible?

It is not.

Nationally, we should redefine health care as not only for people who fall ill, but also for those who are at risk for falling ill or developing chronic conditions. Health care reform must shift dollars to wellness, prevention and early intervention programs that keep people out of our costly health care system in the first place.

Most people with chronic disabilities are elderly. In 2004, 38 percent of hospital beds were filled by patients over 65 years old; by 2030, the percentage is expected to increase to 62 percent. These chronic conditions often develop after costly and inhibiting conditions like bedsores, nosocomial infections and deconditioning, leading to other costly medical interventions. If we fund the information, resources, and assistance they need, they can live happier, healthier, more productive lives outside of the health care system. After all, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, high blood pressure and other chronic conditions can all be prevented or controlled.

Our current system gives providers — including physicians — incentives to treat chronic disabilities, but not to prevent them. We live in a great country but we spend more per capita on health care than any other country in the world. Unfortunately, we lag behind some others in longevity, as well as in many quality of life measures.

If we do not demand that wellness, prevention, education, personal responsibility and early intervention be the basis of health care reform, it will fail. Incrementally improving the existing system is analogous to building a new house on a flawed foundation. True transformation changes an existing entity into something completely different. It leaves the old for the new.

Let us not forget that almost 2 million seniors die in nursing homes, hospitals, and home care programs every year.1 Catholic health care providers are all in the ministry of providing a respectful and dignified death for those they serve. Advance directives, surrogates, proxies and the like must be part of health care reform.

Health care reform is really about our seniors. They are poorly informed, access the system frequently, and often have multiple chronic conditions that add tremendous cost. We do have an opportunity, however, to make it right. Let us keep them well, improve their lives and reduce the cost of health care and at the same time invest in wellness, prevention and early intervention.

— James Higgins

NOTE

- National Center for Health Statistics, Deaths by Place of Death, Age, Race, and Sex: United States, 1999-2005.