BY: MARK KUCZEWSKI, PhD, JOHANA MEJIAS-BECK, MD, AMY BLAIR, MD, and MATTHEW FITZ, MD

Many Catholics grew up hearing the medieval theological lore about limbo, a place where unbaptized babies go to spend eternity. Because the babies lacked initiation into the Christian community, they were denied the fullness of salvation including a spot in heaven. While we often think of limbo as nothingness and neutral, it is also sometimes theologically postulated as the outer ring of hell. After all, we are created for union with God and others.

Imagining the souls of babies and children existing in isolation and going uncomforted is heartbreaking. Moreover, our sense of justice is offended by the seeming unfairness of this sentence. As they lived their brief lives as children, they cannot be responsible for their unbaptized state. They made no choices that have caused this situation. Yet, they suffer the consequences.

Undocumented youth live in limbo in the United States. Harvard sociologist Roberto Gonzales first articulated this reality in his book, Lives in Limbo.1 Gonzales dubbed being an undocumented immigrant a "master status" because it affects virtually everything one does. There is no life apart from that status. Being undocumented determines a person's prospects for employment, a driver's license, health insurance, a higher education degree, and many other opportunities often taken for granted. Depending on a number of factors, most or all of these things may be virtually impossible. As a result, many undocumented youth spend years just getting by while remaining hopeful that our government will reward their contributions to our economy and society with legislation that will create a pathway to citizenship. They behave as if they are implicitly "earning citizenship."2 Unfortunately, while such legislation that would create a pathway to citizenship has come close to passage on several occasions since 1986, none has become law.

We will outline the challenges undocumented young people face and their unique vulnerabilities. In particular, we will make a case that they are denied opportunities to fulfill their potential as members of the community and relegated to daily uncertainty. We will suggest ways that health care professionals and institutions, in general, and those in Catholic health care in particular, can advocate for them.

STRESS, UNCERTAINTY AND TRUNCATED OPPORTUNITIES

It has always seemed especially unfair that undocumented youth cannot fully participate in our community. Sometimes called "Dreamers," after the never-passed legislation known as the DREAM Act, they were brought to the U.S. as minors. Thus, they have not committed any crime in entering unlawfully or by overstaying a visa. Segregated from equal opportunity, undocumented youths live in a new "Jim Crow" landscape that resembles African-Americans' struggle prior to the civil rights movement.3

President Barack Obama instituted the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program, often called DACA, in an effort to mitigate the biases and unequal environment. DACA provides a two-year, renewable stay of action on their immigration status and provides an Employment Authorization Document or EAD, colloquially known as a "work permit." Those who received DACA are able to work lawfully which, unsurprisingly, greatly increased the range of employment opportunities and their wages. All states grant driver's licenses to DACA recipients and educational achievement has significantly increased with DACA recipients entering colleges at a rate close to their citizen peers.4

Nevertheless, members of this population have significant barriers to full participation in their communities, including ineligibility for federal "benefits" such as student loans, provisions of the Affordable Care Act and Social Security benefits. Thus, they remain at risk for diminished quality of life.

DACA has provided more stability than these young people had previously and opened more educational and work opportunities. DACA excluded significant numbers of young persons, however, as some were "too old" as they had to be under the age of 31 at the time of implementation in 2012. As an example, journalist Jose Antonio Vargas who was 31 years old in 2012 did not qualify despite having lived in the United States since the age of 12. Similarly, the earliest one could apply for DACA was at age 16. Thus, some young persons could only "age into" DACA eligibility over time. However, under the terms of President Obama's executive memorandum, no young person who arrived in the U.S. after June 15, 2007, is eligible for DACA. As a result, there are now many young adults or people approaching adulthood in the United States who will never reap the benefits of DACA. Absent a legislative intervention, they will always remain fully undocumented with all the associated problems, including the risk of being detained and deported.

Furthermore, the undeniable context of the lives of undocumented youth is uncertainty. Although undocumented youth in general and DACA recipients in particular are sometimes characterized as the rock stars of the immigration reform movement, because they are often described in terms of their achievements and do not carry the stigma of having violated immigration laws by their actions, they have never had the comfort of well-founded expectations regarding their future. On a number of occasions over the last 15 years, they have watched the DREAM Act and comprehensive immigration reform gather momentum only to fall short of passage.5 The creation of DACA enabled more than 700,000 undocumented youth to gain a degree of predictability regarding their situation for a period of time. Unfortunately, even this small concession to normalcy has been undermined.

On September 5, 2017, President Donald Trump rescinded DACA. As DACA was created by a presidential memorandum, the chief executive of the United States may choose to do away with it as well. Several district and circuit courts have held that the Trump administration did not meet certain process and rationale requirements for rescinding the program. These federal judges have ordered that the program remain open for current DACA recipients to renew their work permits while the cases make their way through the judicial system. Unfortunately, the DACA program was closed to new applications, thereby preventing anyone from aging into the program. So, most undocumented youth do not have the protections and opportunities afforded through DACA. And those who do, live with the uncertainty about whether DACA will be ended with a court decision in the foreseeable future.

SANCTUARY DOCTORING

The overwhelming uncertainty and denial of opportunity are extremely stress-producing for undocumented immigrants and place young people at particular risk. For this reason, the American Academy of Pediatrics has created an extensive online toolkit for physicians treating this population.6

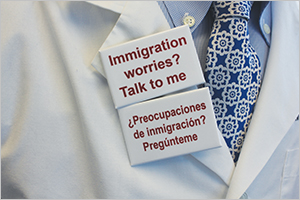

As an additional resource, the authors of this article previously created the Sanctuary Doctoring website7 to provide an easy-to-use and systematic approach for health care providers.8 Because of the unique needs of undocumented youth, we devoted a significant portion of the materials to addressing their needs.

In general, the Sanctuary Doctoring approach has four aims: to open a dialogue; to provide reassurance; to provide resources; and to begin to develop an emergency plan. In general, this approach empowers undocumented patients to raise the issue of stresses and problems arising from their immigration status. Modeled on other public health campaigns such as domestic violence awareness, the Sanctuary Doctoring approach normalizes such concerns. Physicians and other health-care professionals can wear buttons that encourage patients to talk to them about immigration-related concerns; the Sanctuary Doctoring flier tells patients that they can open such a discussion simply by handing the flier to their doctor.

This approach is meant to avoid frightening patients who might misinterpret being asked about their immigration status. However, physicians who have a rapport with their young patients or their parents may consider opening a dialogue more directly when there are signs or symptoms of social stress. For example, physicians may say that they have information that can be very helpful to young people who have difficulties related to immigration status and ask if they would like these materials for themselves or their friends and family.

Reassuring the patient takes two forms. First, physicians should reassure patients that their immigration status will not be written in their medical record. This is especially important for patients who do not have the protections of DACA.9 Second, physicians should reassure patients that many young people are currently facing these issues and injustices. While some undocumented youth are very well-networked, many may be isolated and wrestling with their struggle in isolation. This increases anxiety.

As a result, we have created a Sanctuary Doctoring template flier that can be customized by adding regional resources to help these patients. The template provides links to national legal resources and encourages clinicians to add local resources, such as immigrant advocacy groups that offer assistance with DACA renewals or can refer them to reputable attorneys who may provide services on a sliding scale or pro bono basis, if necessary. The links to Dreamer advocacy organizations can help patients stay informed on the latest developments related to DACA and proposed legislation. With this information, Dreamers may be able to plan their renewals and maximize the amount of time they are protected by DACA should the U.S. Supreme Court take up any of the district or circuit court decisions and strike down the program. The flier also refers them to several organizations that highlight scholarships for which undocumented students are eligible. We encourage local clinics to research educational resources in their area and add them to the template. The information helps undocumented youth to build networks and support their development in spite of their systemic separation from opportunity.

Finally, the Sanctuary Doctoring materials encourage patients and families to develop an emergency plan for a worst case scenario, such as the detention and/or deportation of one or more family members. It is beyond the scope of a clinician to make a full emergency plan with the patient and their family. However, there are some practical recommendations physicians can make. First, the physician or other health care professional should suggest that parents update the emergency contacts form at their child's school. It is important that the child will be picked up by the family member or person of choice should the parent be detained. Similarly, the child should be advised to memorize at least two phone numbers — their parent's and one other trusted adult who will assist if the family is detained as a unit. It is important that young people be able to reach out for help in the event that they are separated from their electronically recorded contacts.

THE COMMUNION OF SAINTS

What should Catholic health care do for immigrants in political limbo, and why should it be done? It is unjust to penalize young people who have broken no law, and, in addition to that, Catholic social teaching contributes to our understanding of the situation and makes action by Catholic institutions imperative. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has been a leading voice for compassionate immigration reform for two decades.10 Catholic social teaching sees undocumented migrants as reluctant migrants who typically leave their homes owing to unacceptable social and economic conditions.11 As a result, there is a natural right to migrate or at least a presupposition in favor of welcoming the stranger. As human beings also contribute to creation through their labor, work has inherent dignity. It is by nature unjust for a community to share in the benefits of the labor of others and to deny those laborers participation in its fruits.12 The imperative to advocate for justice for immigrants is made all the stronger through the current vilification of immigrants in the political discourse. The message of the Gospel is very straightforward. Christians stand with those who are marginalized and outcast.13 In such a climate, the agenda for Catholic health care should contain several elements.

Catholic health systems can make an effort to support these young people, whether as patients, students or employees. As we've said, health care professionals can use the materials from the Sanctuary Doctoring site or similar materials in a structured way with patients to be enormously helpful to this at-risk population. The needs of these patients are immediate.

Second, Catholic health care institutions can partner with local educational institutions to foster educational and employment opportunities for undocumented youth. A notable example of this is Trinity Health's investment in student loans for medical students who are DACA recipients at the Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine.14 Such an investment creates opportunity and empowers these young people, providing them with an education and the chance to become stronger advocates for themselves and others as members of the medical profession. Catholic health care institutions can echo this approach by creating or donating to scholarship funds for undocumented students at local colleges and universities. Furthermore, employing DACA recipients further embeds these young people within the fabric of the community. And, health care systems may be able to create short-term internship opportunities with local colleges and universities that are available even to youths who lack a work permit.

Third, Catholic health care must take on a greater public role in advocating for these at-risk youth. Catholic colleges and universities have been constant and eloquent advocates for the equitable treatment of undocumented youth because as students, they are constituents. Catholic health care institutions have sometimes advocated on behalf of these populations. However, advocacy for undocumented populations has often been a relatively low priority because of the need to focus on other health policy concerns such as preserving the Affordable Care Act. The equitable treatment of undocumented immigrants can seem to be less clearly a health care issue. Furthermore, Catholic health systems located in states that are more electorally conservative may fear alienating their elected representatives and other members of the community. It is important that Catholic health systems use their influence to help recast the narrative in these locales. Lack of a permanent and lawful immigration status impacts health and causes our health system to function less efficiently for all.15

Catholic health care systems can advocate for their employees who are DACA recipients and undocumented youth who are their patients. This is even more important in states in which the political climate is less hospitable. Catholic health care institutions can work with their representatives to come to share a mutual understanding that undocumented youth in their communities need their representation to further enable their contributions to those communities.

A moral imperative for Catholic health care is to end the chasm that separates us from the limbo in which these youth live. Catholic health care must proclaim prophetically that these young people are us, and we are them. We must be in communion with them in the fullest sense — their struggles must become our struggles. We can no longer think of "them" as an "issue" that is related but marginal to the mission of Catholic health care. In recognizing their long-standing plight, we are called to accompany them as neighbor, as brother and as sister. To end the social and political limbo undocumented youth are in, we must proclaim the Kingdom of God and live it together.

MARK G. KUCZEWSKI, PhD, is the Fr. Michael I. English, SJ, professor of medical ethics and the director of the Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics at the Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine.

JOHANA MEJIAS-BECK, MD, is a resident (post graduate – year one) in the internal medicine and pediatrics (Med-Peds) program at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, Truman Medical Center. A former DACA recipient, she plans to dedicate her career to underserved patients, especially immigrant populations.

AMY BLAIR, MD, is an associate professor of family medicine at the Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, and director of the Center for Community and Global Health.

MATTHEW FITZ, MD, is a professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine where he directs the Internal Medicine clerkship. He also directs the Loyola Access to Care Clinic, a primary care safety net clinic in Maywood, Ill.

NOTES

- Roberto G. Gonzales, Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016).

- Jose Antonio Vargas, Dear America: Notes of An Undocumented Citizen (New York: Harper Collins, 2018), 71.

- Mark Kuczewski, "The Really New Jim Crow: Why Bioethicists Must Ally with Undocumented Immigrants," American Journal of Bioethics 16, no. 4 (2016): 21-23.

- Randy Capps, Michael Fix, Jie Zong, "The Education and Work Profiles of the DACA Population," Issue Brief, Migration Policy Institute, August 2017, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/education-and-work-profiles-daca-population.

- Michael Bowman, "Comprehensive US Immigration Reform Remains Elusive After Years of Failed Plans," Voice of America, April 4, 2018. https://www.voanews.com/a/comprehensive-us-immigration-reform-elusive/4332393.html.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Immigrant Child Health Toolkit, https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Immigrant-Child-Health-Toolkit/Pages/Immigrant-Child-Health-Toolkit.aspx.

- Resources on Treating Fear: Sanctuary Doctoring at https://LUC.edu/sanctuarydoctor.

- Mark G. Kuczewski, Johana Mejias-Beck, Amy Blair, "Good Sanctuary Doctoring for Undocumented Patients," AMA Journal of Ethics 21, no. 1 (2019): E78-85. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/good-sanctuary-doctoring-undocumented-patients/2019-01.

- Grace Kim, Uriel Sanchez Molina and Altaf Saadi. "Should Immigration Status Information Be Included in a Patient's Health Record?," AMA Journal of Ethics 21, no. 1 (2019):8-16.

- National Conference of Catholic Bishops/United States Catholic Conference, "Welcoming the Stranger Among Us: Unity in Diversity," 2000, http://www.usccb.org/issues-and-action/cultural-diversity/pastoral-care-of-migrants-refugees-and-travelers/resources/welcoming-the-stranger-among-us-unity-in-diversity.cfm.

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Justice for Immigrants, "Root Causes of Migration," 2017. https://justiceforimmigrants.org/what-we-are-working-on/immigration/root-causes-of-migration.

- Mark Kuczewski, "Here's What We Are Supposed to Believe About Immigration as Catholics," America, September 29, 2017, https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2017/09/29/heres-what-we-are-supposed-believe-about-immigration-catholics.

- Mark G. Kuczewski, "DACA and Institutional Solidarity," in M. Therese Lysaught and Michael McCarthy (eds.), Catholic Bioethics & Social Justice, (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018).

- Betsy Taylor, "Trinity Health Funds Medical School Loans for Undocumented Immigrants," Catholic Health World, October 1, 2015, https://www.chausa.org/publications/catholic-health-world/archives/issues/october-1-2015-chw/trinity-health-funds-student-loans-for-undocumented-immigrants-medical-students.

- Mark G. Kuczewski, "How Medicine May Save the Life of US Immigration Policy: From Clinical and Educational Encounters to Ethical Public Policy," AMA Journal of Ethics 19, no. 3 (2017):221-233, http://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/2017/03/peer1-1703.html.