BY: GARY SLUTKIN, MD

— Thomas S. Kuhn, American physicist, historian and philosopher of science

In many cities across the United States, we see a familiar scene unfold virtually every weekend — dozens of youth between the ages of 15 and 24, most of whom are black or Hispanic, are injured or killed in major cities including Baltimore, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans and Detroit. Outcries spread through neighborhoods and the nation; most are focused on the "senseless violence."

Mothers lose children daily to "senseless violence." Youth and adults are in prison, some for their entire lives, due to "senseless violence." But why do we believe violence is senseless? Is it because we believe that the people committing the violence are doing so for no reason? Do we think they have no sense? Or could it be that violence is occurring for reasons that make no sense to us? In other words, if we think of something as senseless, maybe we just don't understand it sufficiently.

For example, when 17th-century scientist Galileo Galilei was able to observe and track the moons of Jupiter through a rudimentary telescope, he saw the moons were not behaving in the way people at the time understood and explained the heavens. To explain what he saw, Galileo revised the accepted beliefs of the day — that the Earth was the center of the cosmos, and the heavens rotated around the Earth.

Galileo's observations and conclusions challenged the moral authority and scientific paradigms of his era. As his conclusions were affirmed, society was able to better understand the way the stars and planets move and make fundamental adjustments in thinking and teaching. Thus by searching for reasons to explain why his scientific observations didn't fit the prevailing beliefs, Galileo helped us make sense of and better explain our world and design new ways to advance science.

MAKING SENSE OF VIOLENCE

The issue of lethal violence in the U.S. is a much more specific issue than gun control policy, law enforcement or providing mental health services to populations traumatized by repeated and long-standing exposure to violence. Recent advancements in neuroscience, behavioral science and epidemiology give us an understanding that violence is transmitted and how people exposed to violence process what they have witnessed or been exposed to, and then behave toward others.

Science has proven for more than 50 years that people acquire behavior through imitation — scientists and educators sometimes call this "social learning." The advantages of doing what parents, older siblings, other relatives and peers do by imitating them are obvious. Yet because people copy behavior, it means behavior witnessed over time is contagious.

It also is well established that individuals adopt violent behaviors through the unconscious modeling of observed behaviors. The additional physiological effects from both witnessing violence and from trauma accelerate the contagion.

In short, violence is transmissible. It behaves like all epidemics. It has the exact characteristics of a contagious disease. Violence as a public health problem is not merely a metaphor, it is scientific fact.

THE PANEL

Three years ago, a panel of scientists from multiple disciplines, including epidemiology, infectious diseases, neuroscience and social psychology, convened to explore the scientific evidence for violence behaving like a contagious disease. The 2012 Forum on Violence Prevention, sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences' Institute of Medicine, reviewed dozens of studies spread throughout these and other social and health science disciplines and a host of measures ranging from observational studies to functional MRI studies to pilot testing of new approaches to violence prevention.

In the way scientists Galileo (and then Johannes Kepler) and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (and then Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch) drew on the new instruments of telescopes and microscopes to learn and understand, those gathered at the IOM meeting drew on scientific evidence, connected dots and explored the mechanisms — the "how to" side. They concluded that the brain processes violent input — observing violence or experiencing trauma by violence — in the same way the lung processes tuberculosis by producing more tuberculosis, or the intestines process cholera by producing more cholera. The brain processes violence by producing more violence, just like an infectious disease.

THE CURE VIOLENCE MODEL

I am a physician and epidemiologist by training. I moved to Somalia in 1985 to work to reverse tuberculosis and cholera epidemics, and I joined the World Health Organization in 1987 on a seven-year effort that was successful in reversing the AIDS epidemic in Uganda and other countries.

My WHO work provided me extensive experience in the use of disease control techniques to reverse such epidemics. Since 1995, I have been applying these techniques to the issue of lethal urban violence. I founded Cure Violence — originally launched as CeaseFire Chicago — in 2000, using a science-based methodology to understand human violent behavior and successfully interrupt and prevent its spread.

When I began this work, the problem of violence was stuck. Policy leaders throughout the United States were focused solely on law enforcement, which has mixed results and does little to prevent violence. Yet science has proved that the greatest predictor of violence is a preceding case of violence, just as a case of flu is known to have been preceded by another case of flu. As a physician and epidemiologist, I wondered if there could be a connection: Could a health epidemic perspective on escalating violence in urban communities interrupt and prevent violence from spreading? It may seem counterintuitive, but if violence is transmissible, just like a contagious disease, that might be good news, because public health has an incredibly strong and proven track record of successfully reversing epidemics. Could the methods of changing behavior and social norms that physicians use to reverse epidemics work in addressing violence?

The answer is yes.

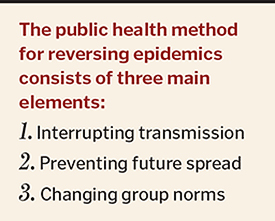

To detect and interrupt violence, the Cure Violence model deploys new types of workers, called violence interrupters, who are highly trained to locate potentially lethal, ongoing conflicts in a community and interrupt and respond with a variety of mediation techniques. The goal is to prevent imminent violence and to begin changing the social norms around the perceived need to use violence.

Violence interrupters are culturally appropriate workers who live in the affected community and are well known to those at high risk of engaging in an act of violence. The interrupters may have a high-risk background themselves, they may have been in prison, but they have made positive changes in their behaviors that have been in place for some time. Interrupters receive specific training on methods for detecting potential shooting events, mediating conflicts and remaining safe in dangerous situations.

By interrupting conflict that can lead to violence before it becomes lethal, the interrupter immediately cuts off a chain of violent events commonly referred to as retaliations. Interruption also prevents other people from being exposed to a potentially violent act, thus inhibiting transmission of the behavior and perpetuation of the norm.

OUTREACH WORKERS

To help prevent future spread, Cure Violence also employs a strong outreach component to identify and change the thinking of the highest risk youth. Outreach workers work side-by-side with violence interrupters, acting as mentors, working with each client multiple times per week, conveying a message that reinforces rejection of the use of violence and assisting clients in obtaining new skills and individually identified services, such as job training, drug abuse counseling, anger management counseling and trauma support.

Outreach workers develop risk reduction plans focused on moving each high-risk participant from accepting the use of violence. Outreach workers also are available to their clients during critical moments — when a client needs someone to help him or her avoid a relapse into violent behavior. What particularly sets the Cure Violence model apart is the participants' level of risk: The model calls for working with those at highest risk for involvement in violence.

To change group norms in the community, Cure Violence uses public education campaigns, community events, community responses to every shooting and act of violence and community mobilization to change group and community norms related to the use of firearms.

SOCIAL NORMS

In most high-violence communities in the U.S., the social norms youths encounter virtually require them to respond violently to petty grievances, acts of disrespect and small financial problems. Yet, if new norms rejecting the use of violence or existing norms opposing violence are communicated repeatedly to everyone in a community, these new norms gradually begin to create a barrier to violent behavior that becomes difficult to overcome.

In the language of vaccination against infectious disease, when new norms rejecting violence are established in a community, these new norms often are referred to as "herd immunity" to violence.

Multiple independent evaluations by organizations including the Centers for Disease Control, the U.S. Justice Department, Northwestern University and the University of Chicago have confirmed the effects of the Cure Violence health model, showing up to 73 percent reductions in shootings and killings.

International adaptations of the Cure Violence model have demonstrated large reductions in violence in cities from Cape Town, South Africa, to Juarez, Mexico. In three communities in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, the most violent city in the world, program implementation has coincided with 73 percent to 86 percent reductions in shootings and killings. In the target area in Cape Town, South Africa, there has been a reduction of 52 percent in gang-related killings. In Loiza, Puerto Rico, there was a 50 percent reduction in killings associated with first year of implementation. In Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, after implementation of Cure Violence, killings dropped by 24 percent.

Furthermore, currently dozens of programs are based on this understanding of violence as a contagious health problem, including several city and state health departments effectively preventing violent events through a Cure Violence approach. In fact, there is a growing network of hospital programs that prevent shootings — or "relapses."1

PUBLIC POLICY

U.S. policymakers are just beginning to understand the contagion of violence model and apply it to analyzing behavior in other fields. Just as we have discovered it is more effective to treat drug addiction as a health issue than to punish it, it likewise makes more sense to prevent violent events, provide treatment to people at high risk and change social norms.

Like all potentially harmful behaviors — drug addiction, smoking, eating too much, exercising too little and risky sexual behavior — violent behavior can be understood, diagnosed and successfully treated using a health approach. Although violence involves harm to others and at times, even self, the same techniques that prevent the spread of cholera, tuberculosis, avian flu and the Zika virus can be used to change behaviors.

Scientists' understanding of violence and its causes continues to evolve. It will require constant assessment and re-evaluation, just as Galileo's work was refined by Kepler and countless others. Science has shown policymakers enough, however, to begin to change and implement the health model to reduce violence and save lives now.

Public health epidemiologic methods add to law enforcement efforts, which still are needed and complementary. But if law enforcement, gun control policy and other traditional responses represent the limit of the national response to violence, the transmission of violence in the United States will continue, leading to more high-profile and devastating events, as well as leaving unchanged social norms that will perpetuate the contagion.

A truly comprehensive and effective solution to the epidemic of violence must include a scientifically grounded public health strategy based on the essential principles used to fundamentally reverse other epidemics.

Science has shown that understanding violent behavior as contagious, indeed, as an actual epidemic, and treating the epidemic using a public health approach, has significant impact and saves lives. To truly care for people and communities, society must move beyond the antiquated notion that violence is committed by "bad people" to recognize that violence is committed by people who have been exposed to violence.

We must forge new health policies and practices that reflect this reality. Equipped with the knowledge that it is a contagious human behavior, health sector professionals can help reverse the problem of violence by serving as visible advocates for change and helping shift fundamental thinking among both policymakers and the general public. Just as the Cure Violence model uses violence interrupters to stop the spread of violence in high-risk communities, health professionals also can serve as credible messengers among peers and policymakers to build awareness around this new scientific fact, confirmed by the Institute of Medicine: Violence is a health epidemic.

GARY SLUTKIN is the founder and CEO of Cure Violence and professor of epidemiology and international health at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health. For more information about the Cure Violence health approach, see www.cureviolence.org.

NOTE

- See the National Network of Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs (www.nnhvip.org) website for a list of participating hospitals.