Confronting Racism by Achieving Health Equity

Racism within any context is an affront to the core values of Catholic social teaching, which acknowledges the inherent dignity of each person, calls for the furthering of the common good and seeks justice through solidarity. Catholic health care recognizes the profound effect racism has on the health and well-being of individuals and communities and is committed to addressing the systemic causes of health disparities among underserved and vulnerable populations. As such, we are committed to working with partners who share these convictions to implement wide-sweeping change and eliminate the racial inequities in our marginalized communities.

Health Equity Stories

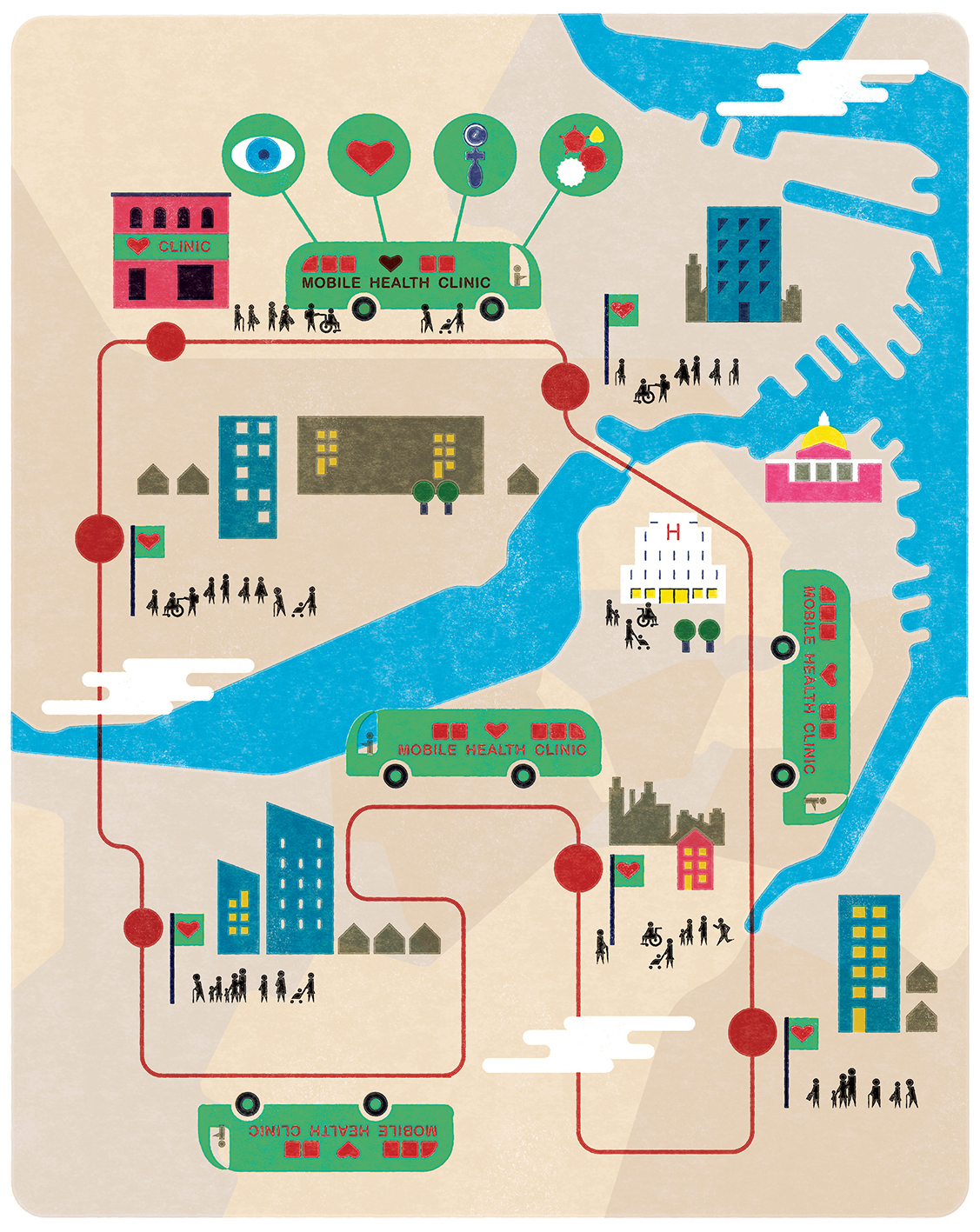

Season 4: Episode 2 - Roadmaps to Health Equity

– Pope Francis