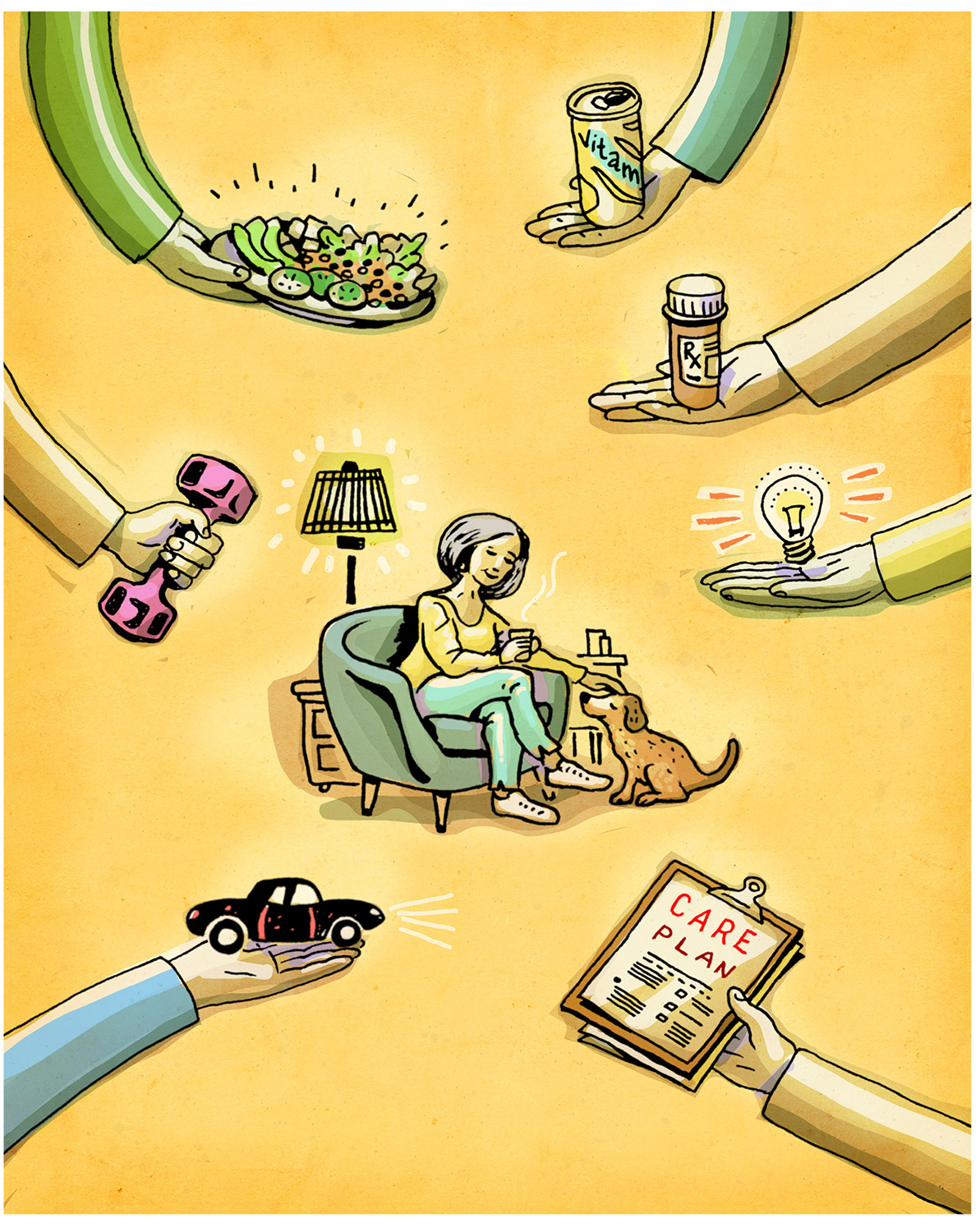

As leaders in well-being, the Catholic health ministry is called to foster an environment of healing where patients, co-workers and the local community may flourish. Together, we represent a community of over 700,000 associates, united by the healing ministry of Jesus and the enduring vision of our founders, dedicated to advancing human flourishing.

Renew: Rhythms for Well-being

The Renew resources have been designed with your team huddle or department meeting in mind. Introduce these concepts by discussing the key questions provided for each day, engage in dialogue and explore how purposeful days can promote well-being and abundant living. May the podcasts, video reflections, articles and prayer resources support you to integrate well-being practices into your daily life and encourage your colleagues to do the same.

CHA Podcasts

Season 5: Episode 15 - Using AI to Protect Caregiver Well-Being

Technological advances are nothing new for caregivers, who have been saturated with new tools to "help" them for decades. But are those tools actually helping? And what can the latest innovations do to alleviate the burden caregivers face on a day-to-day basis?

Dr. Heather Schmidt, System Medical Director, Healthy Work and Wellness at SSM Health, and Dr. Ann Cappellari, Chief Medical Information Officer and System Vice President at SSM Health, join the show to discuss their findings on how artificial intelligence can assist caregivers in their well-being. They discuss how technology has often added to the administrative burden caregivers face, offer insight into tools that help caregivers connect with their patients, and share how AI can help with the workforce shortages that American health care faces.

Season 3: Episode 15 - A Fresh Approach to Well-being in Health Care

Maintaining our own well-being can be a challenge in a world where we’re constantly bombarded with new ideas, challenges, and tasks. When everything feels so urgent, how do we re-orient our minds and take the time to slow down? In a Health Calls special, Diarmuid Rooney, CHA’s Interim Vice President of Sponsorship and Mission Services, and Jill Fisk, CHA’s Director of Mission Services, host an intentional, meditative conversation on well-being and its roots in Catholic health ministry. They discuss the Christian history of meditative practice as well as the benefits of mindfulness and meditation before Diarmuid leads listeners in a simple exercise that will refresh your spirit.

Resources:

Season 3: Episode 16 - Well-being for Busy Health Care Leaders

Increased mindfulness is vital to our well-being, but it requires a significant time commitment. For those with full schedules, how do we begin to build these practices into our busy lives?

In a Health Calls special, Diarmuid Rooney, CHA's Interim Vice President of Sponsorship and Mission Services, and Jill Fisk, CHA's Director of Mission Services, discuss the benefits and importance of incorporating mindfulness exercises into our every day lives. They suggest a few easy ways to get started before Diarmuid leads listeners in a simple exercise that will refresh your spirit.

Resources:

- A Fresh Approach to Well-being in Health Care: A Health Calls Special Episode

- Visit CHA's ReNew Year page to explore a new foundational approach to Well-being in Catholic Health Care.

- "Be Still" Meditative Video

- "Peace in Anxiety" Meditative Video

- Read Sarah Reddin's recent Health Progress article, "Flourishing Through Formation: Catholic Identity Is Reinforced With Thoughtful Approaches"

- Contemplative Outreach, a spiritual network committed to living the contemplative dimension of the Gospel

- Read Margaret J. Wheatley's article, "Can We Reclaim Time to Think?"