BY: FR. THOMAS NAIRN, OFM, PhD

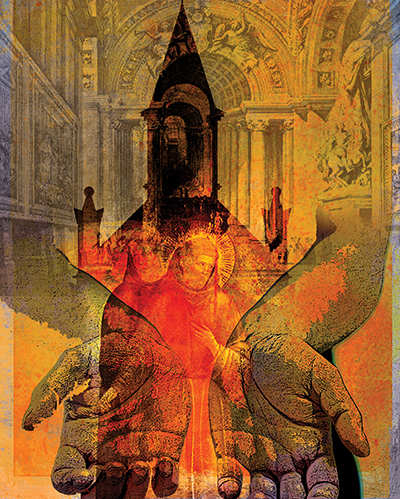

Roy Scott

The period from the 11th to 13th centuries witnessed the rise of a money economy in Europe. Cities grew and multiplied; more and more land was cultivated, increasing the wealth of landowners; and a new-sprung merchant class made it possible for those who were not part of the aristocracy to accumulate wealth.1

Partly in reaction to these changes in the larger society, a new form of religious life emerged in the early 13th century — the so-called mendicant orders.2 These religious communities were different from the great monastic orders such as the Benedictines or Cistercians, which were founded hundreds of years earlier. Members of the monastic orders devoted themselves to prayer, learning and manual labor while living and working together within the walls of the monastery. Although individual monks took the vow of poverty, monastic communities owned land and goods. Over the centuries, the monasteries became powerful centers of education, the healing arts and the preservation of culture, often accumulating great wealth.

In contrast, members of mendicant orders were itinerant preachers, moving from town to town to preach the Gospel. Consciously modeling themselves on the disciples of Jesus, they went about two by two and were to "take nothing for the journey, neither knapsack, nor purse, nor bread, nor money nor walking stick."3 The form of poverty embraced by these religious communities involved the renunciation of all ownership of goods, communal as well as individual. To survive, the mendicant friars asked for alms as they preached, traveled and worked along the way.

Giacomo Todeschini, professor of medieval history at the University of Trieste, Italy, described the mendicant orders' absolute poverty this way: "The choice to be poor was realized in a series of gestures: abandonment of one's paternal house, a wandering life, ragged appearance and clothes, manual work as scullery-man and mason, and begging without shame."4

The dedication of the mendicant orders to "begging without shame" produced a different dynamic from that of monastic orders. Voluntary absolute poverty created an institutional dependency. The mendicant communities relied on contributions — in other words, they needed donors — in order to survive. Thus, early forms of philanthropy are what made it possible for mendicant communities' work to go forward. A mutual relationship evolved between the mendicant orders and those who supported them.

MEDIEVAL CONTROVERSY

St. Francis of Assisi explained to his followers that the spiritual motivation for begging was to follow the example of the poor and humble Christ:

"Let all the brothers strive to follow the humility and the poverty of our Lord Jesus Christ and let them remember that we should have nothing else in the whole world except, as the Apostle says, having food and clothing, we are content with these. … When it is necessary, they may beg for alms. Let them not be ashamed and remember, moreover, that our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of the all-powerful living God, set His face like flint and was not ashamed. He was poor and a stranger and lived on alms — He, the Blessed Virgin, and His disciples."5

Many in the church objected, however, to the radical poverty embraced by the mendicant orders, in part because of its similarity to what was being espoused by some itinerant groups considered heretical,6 but also because begging was considered unseemly for members of religious orders.

In the early 1250s, fewer than 50 years after the founding of the Franciscan Order, one of the masters of theology at the University of Paris, William of St. Amour, offered several arguments against the style of religious life that the mendicant orders developed. He claimed that their unwillingness to appropriate anything for themselves was not an indication of grace but an occasion of sin, because it placed the life and health of friars in jeopardy. He maintained that "the common property of monks was morally superior to the dangerous innovation of absolute poverty."7 He especially objected to the fact that friars begged for alms.

"It is true that if a person is unable to work or maintain himself in any other way, he begs without sinning," he wrote. "But if a person can obtain his food by working, if that person begs, he is not one who is poor in spirit. Rather he wants his poverty to be profitable. And if he is a religious, he displays his holiness as venality. … Thus this person is not perfect, but a sinner."8

Such criticism called for response. St. Bonaventure of Bagnorea, the medieval Franciscan theologian and doctor of the church, wrote two book-length treatises on the subject, the Disputed Questions on Evangelical Perfection (1255) and Defense of the Mendicants (1269).9 In the first work, St. Bonaventure refuted William of St. Amour's criticism, indicating that there are three different forms of begging: In the first, a person begs because he or she is poor. St. Bonaventure explained that this form of begging is unfortunate for the person but endurable if borne with patience. In describing the second form of begging, St. Bonaventure accepted, in part, William's critique. In this form, according to the saint, a person begs "either to foster a life of ease or to amass money, or both." He added that this form of begging "arises from the corruption of sin" and that those who beg in this manner should be reproved. Finally, there is a form of begging that "occurs when someone begs as a way of imitating Christ or proclaiming the Gospel of Christ or both." He insisted that when one begs in the name of Christ, that person is not a sinner but, rather, "edifies his neighbor."10

BEGGING AS SPIRITUAL PRACTICE

In explaining the third form of begging, St. Bonaventure articulated a spirituality that is at the heart of the mendicant orders' embrace of radical poverty. This spirituality has two dimensions, a vertical dimension uniting the mendicant community with God in imitation of the poor and humble Christ, and a horizontal dimension in relation to the neighbor, establishing a "fellowship of friends, free, equal, and loving."11

The vertical dimension refers back to the words of St. Francis himself when he encouraged his followers to "strive to follow the humility and the poverty of Christ." Franciscan theologian Zachary Hayes explains that these attributes were not accidental to the person of Christ: "In the humility and poverty of the incarnate Word is the historical manifestation of the Son who is pure receptiveness of being and the full loving response to the Father. Thus the incarnation in its concrete form reveals the authentic truth of the human situation."12

In this sense, voluntary poverty does not signify any absence or deprivation. Rather, it is an acknowledgement of the person's radical dependence upon God and openness toward God. Poverty arises from the recognition that everything one has is a gift from God. Reversing the argument of William of St. Amour, St. Bonaventure maintained that voluntary poverty is not a sin. Rather, he asserted, the true sin is claiming ownership and dominion over what is essentially a gift and to desire for one's private use that which is given by God for the good of all.13

GIFTS BETWEEN FRIENDS

The last element of a mendicant spirituality moves the discussion to a horizontal dimension, and it has concrete consequences for the giver of alms, as well as for the one who begs. In a particularly poignant passage in Disputed Questions on Evangelical Perfection, St. Bonaventure explained this dimension as a relationship between friends.

"When a friend asks for a gift from a friend, he violates no law; neither the first friend by his asking, nor the second friend by his giving, nor again the first by his accepting," he wrote. "But the law of charity and divine love involves a greater exchange than the law of society. Therefore, should someone ask that something be given him for the love of God, he commits no offense, nor does he in any way withdraw from the path of perfection."14

Todeschini explains that in return for giving alms, the donor receives "God's love, and all things of the world, even those from Heaven, are nothing compared to it."15

This is not, however, some sort of crude exchange, although it implies a sort of commerce that did not exist for the monks. The friars provided services that people supported by alms. Thus begging "for the love of God" implies interdependence between the giver of alms and the mendicant friar and invites both to a different, more inclusive, vision of society, "one marked at its very beginning by the sharing of all things in common and by the equality of each person in a community of loving relationships."16

For the mendicant orders, such sharing recalled not only the early Christian community,17 but even more especially, humankind in innocence before the Fall,18 by placing the idea of "gift" and giftedness at the center of their spirituality. Sharing in solidarity, St. Bonaventure maintained, is God's original desire for all people.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TODAY

Often philanthropy and fundraising in the context of Catholic health care have been expressed in terms of the donor's sharing in the contributions that health care makes to the community or to society at large. Sometimes religious language also is used, such as "participation in the healing ministry of Christ."

However, if one takes mendicant spirituality seriously, it challenges Catholic health care to understand giving in a more theological way. Whether the challenge is expressly articulated or not, this spirituality encourages donors to recognize that all they have is a gift from God, and, as such, it cannot be hoarded but must be shared.19

It becomes an invitation that the best way to acknowledge one's giftedness is to use one's wealth to help satisfy the needs of others. Such philanthropy is not beneficence or charity, but is, rather, what is owed in justice to one's less fortunate sisters and brothers in a society of friends. Giving is not one-sided; it creates interdependence between the "friend who asks" and "friend who gives." With this in mind, Catholic health care thus can continue the mendicant tradition — and a spirituality — of begging "in the name of the Lord" without shame.

FR. THOMAS NAIRN, OFM, is senior director, theology and ethics, the Catholic Health Association, St. Louis.

NOTES

- See, for example, Giacomo Todeschini, Franciscan Wealth: From Voluntary Poverty to Market Society (St. Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2009), 11-28. See also Lester K. Little, Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy in Medieval Europe (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1978).

- The significant mendicant orders that continue to exist today are the Dominicans, Carmelites, Augustinians, Servites and Franciscans. The term "mendicant" comes from the Latin, mendicare, which means "to ask for alms" or "to beg." Members of these communities are called friars (meaning "brothers") rather than monks. Although in this paper I am writing from a specifically Franciscan perspective, much of what I say can be applied to the medieval mendicant orders in general.

- Francis of Assisi, "Earlier Rule" (Regula Non-Bullata), in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents: Volume I – The Saint, ed. Regis J. Armstrong, J.A. Wayne Hellmann and William J. Short (New York: New City Press, 1999), Chapter 14. See Matthew 10:9-15, Mark 6:7-13, Luke 9:1-6.

- Todeschini, Franciscan Wealth, 61.

- Francis of Assisi, "Earlier Rule," Chapter 9.

- For example, in the 12th century, the Waldensian movement spread through Europe. Its followers were characterized by a strict reading of the Gospels, itinerant preaching and voluntary poverty. The movement condemned the wealth of the Catholic Church and ecclesiastical power. The Fourth Lateran Council denounced the group as heretical in 1215, a time that coincided with the rise of the mendicant orders.

- See Kelly S. Johnson, The Fear of Beggars: Stewardship and Poverty in Christian Ethics (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2007), 53.

- William of St. Amour, The Question of Mendicity, Resp. 4, in the appendix of Bonaventure, Disputed Questions on Evangelical Perfection, trans. Thomas Reist and Robert Karris, (St. Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2008), 290.

- Bonaventure, "Defense of the Mendicants," in Works of St. Bonaventure, vol. 15, trans. José de Vinck and Robert Karris (St. Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2010). Bonaventure wrote this volume in response to a new polemic begun by Gerard of Abbeville.

- Bonaventure, Disputed Questions on Evangelical Perfection, Question II, Article 2, Conclusion: 106-109.

- Joseph Chinnici, "Framing Our Engagement with Society," in The Franciscan Moral Vision: Responding to God's Love, ed. Thomas A. Nairn (St. Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2013), 241.

- Zachary Hayes, The Hidden Center: Spirituality and Speculative Christology in St. Bonaventure (St. Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute Publications, 1992), 142.

- See Chinnici, "Framing Our Engagement," 245.

- Bonaventure, Disputed Questions on Evangelical Perfection, Question II, Article 2, par 36: 105.

- Todeschini, Franciscan Wealth, 70.

- Chinnici, "Framing Our Engagement," 234.

- See Acts 4:32-37.

- For St. Bonaventure, God's original intention for humanity was that all be held in common. Private property was the result of the Fall: "If indeed man had not sinned, there would not have been a division of lands but all would have been in common." See Bonaventure, "Collations on the Six Days," in José de Vinck, The Works of Bonaventure, vol. 5 (Paterson, New Jersey: St. Anthony Guild Press, 1970), 270.

- See Matthew 10:8.