BY: ALFRED W. NORWOOD, M.B.A. and Sr. M. PETER LILLIAN DiMARIA, O.CARM., L.N.H.A.

Age affects us all — and it affects each of us differently. Age affects both our physical and mental abilities; therefore, in any group of elders we are likely to see a wide range of memory, cognitive ability and physical ability. In long-term care we tend to see seniors with decreased abilities and consequently reduced capacity to meet their own needs. Increasingly, we also are seeing elders with a reduced capacity to express and communicate their needs.

An increase in the proportion of these residents in long-term care facilities has resulted in a need to re-evaluate care strategies and reposition and retrain care staff. Along with an increasing proportion of residents with moderate and late-stage dementia, there is an increase in unwanted resident behaviors. Unfortunately this increase in behaviors is concurrent with research findings indicating that managing behavior with medication is ineffective, expensive and can even be toxic; and that decreases in long-term care funding lead to lower staffing levels and less clinician time per resident. It is our experience, however, that introducing proactive behavior management and person-centered care can help any facility overcome these constraints while providing enhanced and improved quality care.

Our Foundress, Mother Mary Angeline Teresa McCrory, lived the Gospel message by her example which inspired a great love for the aged and infirm. As we develop relationships with one another that are deeply rooted in our sense of the holy, we understand the meaning of Mother Angeline's words, "Our apostolate is not only to operate up-to-date homes for the aged. As religious, we bring Christ to every person in our care. Bringing Christ means giving people his compassion, his interest, his loving care — his warmth, morning, noon and night. Bringing Christ also means inspiring the lay people who work with us to give the same type of loving care."

With this philosophy, the Avila Institute of Gerontology, the education arm of the Carmelite Sisters for the Aged and Infirm, along with Alfred Norwood, founder of Behavior Science Inc., Rochester, N.Y., have developed a behavior management program that truly has each person at the center of care; it answers the needs of each person within the context of his or her

specific needs.

Largely due to their progressive loss of abilities, long-term care residents can become easily frustrated, anxious and agitated, leading to problem behaviors. This is especially true for residents suffering from some form of dementia. For them in particular, confusion from over- and/or under-stimulation leads to agitation which, if unresolved, leads to stress, and the automatic production of adrenaline. Adrenaline redirects blood to the muscles, increases blood pressure and heart rate, and induces a "flight or fight" response — which impels the stressed resident to express a behavior. The resident's dementia-impaired conscious processing (memory and cognition), plus disinhibition (due to neural brain loss), impels "fight" (aggression such as yelling, striking out, resisting care etc.) or flight (withdrawal, such as apathy, escape or declining care etc.). This sequence is often summarized as "the progressively lowered stress threshold."1

Because we are living longer, the proportion of older residents in long-term care facilities is increasing. Since the incidence of dementia increases dramatically with age from "5 percent of those aged 71 to 79 to 37.4 percent of those aged 90 and older,"2 the proportion of residents with dementia is also increasing.

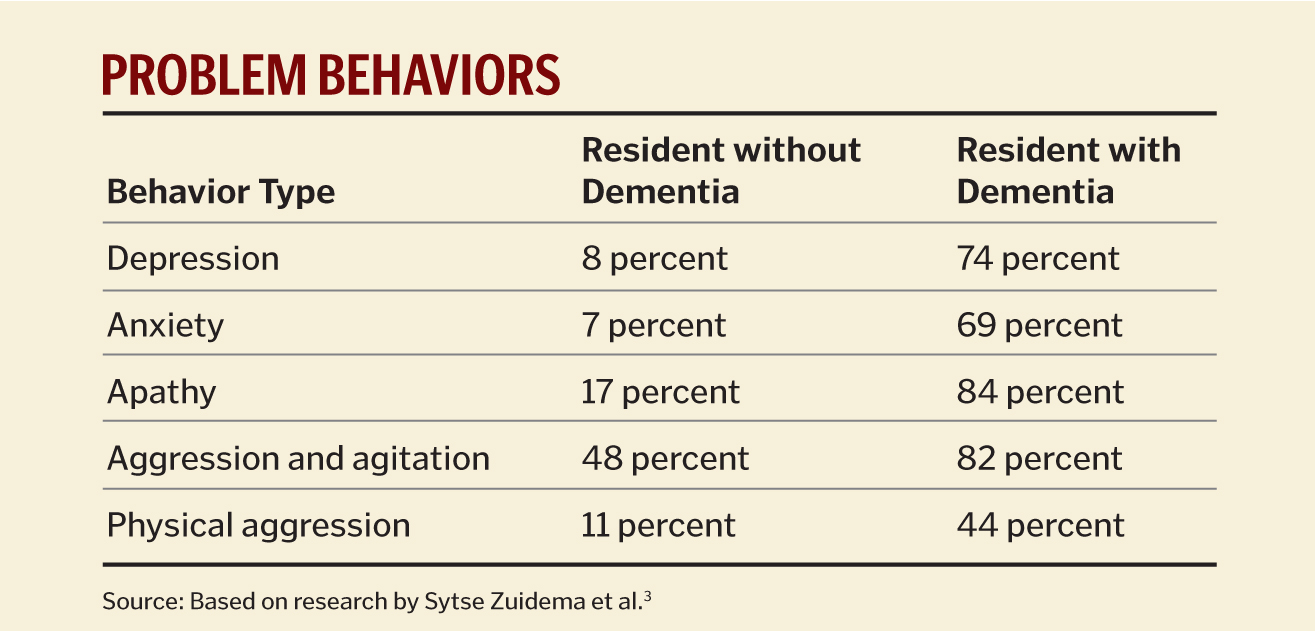

For virtually all long-term care facilities, a by-product of dementia is problem behaviors. While over 80 percent of long-term care residents exhibit such behaviors, residents with dementia often have higher problem-behavior frequency, duration and intensity.3

Although reported infrequently, dementia residents also have episodes of lucidity. A study of dementia residents in long-term care facilities in Sweden indicated that 57 percent had episodes of lucidity, and the study documented that the residents who exhibited lucid episodes were those who had close contact with their caregivers.4

Proactive behavior management techniques grounded in person-centered care make it possible to reduce the frequency, duration and intensity of dementia residents' behavior problems and to increase their periods of lucidity and contentment.

Person-centered caregivers understand each resident well enough to anticipate and avoid an environment that triggers problem behavior. Person-centered care provides caregivers the map for becoming proactive; it allows them to stop behaviors before they start (as opposed to reacting to behaviors after they begin).

Reviewing a page from behavioral psychology helps: We all have behaviors. Behaviors are anything we do. All behaviors are learned; we tend to repeat behaviors for which there is a reward and avoid behaviors for which there is no reward or, worse, which result in something we dislike.

To identify why any behavior occurs, we have to ask, "What was the reward?" In people who have full mental capacity, pinpointing the answer to this question can be difficult. In dementia patients, the answer tends to be more obvious. As dementia progresses, conscious processing (thinking) becomes more difficult, and our residents become more reliant on habits (always showering at 5 p.m.) or over-learned behaviors (turning on a room light with a wall switch). Because they are in a new environment and can't remember what just happened, they have difficulty anticipating what will happen next. Most residents with dementia live in an increasingly unpredictable environment, and that makes them fearful and stressed and on the verge of an unwanted reactionary behavior.

For all of us, unpredictability or novelty is one of the prime triggers of stress. For people with moderate dementia, chronic novelty keeps them at a stress level that autonomically generates adrenaline preparing them for action, that is, "fight or flight." As dementia progresses, it takes only a small change in the environment to trigger stress and stress-related behaviors.5

The key to avoiding problem behaviors is to understand them, attempt to diagnose what caused the resident to get stressed, as well as to identify what "reward" the problem behavior achieved. Through observation that includes knowledge of the resident, the surrounding environment and the resident's background, the caregivers can develop successful behavioral interventions.

For example, suppose Mary, a resident with Alzheimer's disease, yells at mealtimes, disrupting and distressing everyone within earshot. "Yelling at mealtimes" is a brief description of a problem behavior, and though it is accurate, it is insufficient to act upon; it doesn't give staff much information to help figure out a way to resolve it. However, after several observations and some thought, the behavior might be better described this way: "It appears that when Mary is at the dinner table and someone else is served before she is, Mary yells. When this happens, staff stop what they are doing and immediately bring Mary her dinner."

A complete analysis of Mary's behavior could lead staff to understand two things: It seems that for Mary, it is stressful and anxiety-producing to be given no food at the dinner table while she can see other people being served. Her reaction is to yell, and that behavior brings a "reward" — her food, right away — so she will likely continue to yell at mealtimes with increased frequency and intensity.

The more detailed description of Mary's mealtime yelling therefore gives staff members clues towards what might be triggering the behavior and what "rewards" Mary perceives. Based on those observations, her caregivers can talk about interventions that might take the stress out of Mary's mealtime so she never starts yelling at all. For example: 1) Do not bring Mary to the table until her food is ready to be served, or 2) Bring Mary to the table, but always serve her first, or 3) Provide Mary with a distractive activity to do at the table until her meal can be served.

Person-Centered Care

We have found that all behavior is communication. Notice that focusing on deciphering the specific circumstances and trigger for Mary's problem behavior helps her caregivers figure out a proactive intervention. They seek to address Mary's personal need — that is, to prevent or minimize the stress that results in her mealtime yelling before stress starts to build.

Person-centered care is a team sport; without sharing, it doesn't work. For example, a resident we'll call Margaret yelled at bedtime every night. Upon examination, it turned out that she yelled every night but Friday. We discovered that on Friday nights a relief staffer worked with Margaret. When asked why Friday bedtimes were different, Margaret's regular aide said she had never met the other caregiver; they worked completely different shifts. We suggested that the Friday caregiver knew something critical to optimum care for Margaret that regular staff did not know. After a scheduled meeting, the regular staff found that because of arthritis in her left hip, it was painful for Margaret to be lifted into bed in a way that put weight on her left side — the way regular staff had been transferring for years. The Friday caregiver also had figured out that Margaret hated having lotion applied to her skin and preferred powder.

It turned out that simply sharing information was the answer for eliminating Margaret's yelling behaviors and improving her care. Once everyone knew how to keep Margaret comfortable — careful of the bad hip, and the use of powder, not lotion — Margaret's yelling at bedtime stopped.

Mary's and Margaret's stories exemplify ways that knowledge, proactive techniques and innovative strategies can help staff identify behavioral triggers and resolve or eliminate challenging behaviors. Learning and using such proactive behavior management skills is particularly important and effective in cases of dementia, a diagnosis that affects 80 percent of the aging population within long-term care facilities.6 Since many problem behaviors such as wandering or hoarding are common among such residents and cannot be addressed pharmaceutically, proactive behavioral options need to be explored.

It takes education, training and practice for staff members to understand the clinical progress of dementia and to apply that knowledge for the benefit of each person with some type of dementia who is in their care. Presently there are over 60 recognized dementia types and causes — Alzheimer's is only one — and each type of dementia brings with it many different, complicated changes in the brain and different modes of behavior. Gaining and understanding a valid diagnosis, then, is the initial step to understanding the origins of behavior problems and identifying triggers.

In proactive behavior management that is person-centered, effective behavior or mood management is everyone's job. It may be implemented only when all staff understand:

- The difference between age-associated and diagnosed dementia-related decline

- How this decline impacts residents' functional ability, needs and communication

- How behaviors may be observed and defined in terms that suggest alternative interventions

- How to select the best interventions and include them in a plan of care

- Why and how to document and track behavior, interventions and intervention results

- That residents change over time, which can warrant changes in their care plans and interventions

- The importance of knowing the resident and developing a relationship that builds a partnership for care

- That caring for the aged is a privilege and a vocation (a call) to the healing ministry and mission of Jesus

The Behavior Management Team

Establishing a behavior management team is the best way to begin using behavior management techniques. The behavior management team is responsible for assessing the educational needs of the staff, residents and families, identifying and providing the proper educational programs and assigning the appropriate personnel to care teams.

A care team might consist of three or four caregivers, including social workers, activities personnel, nurses, aides and/or pastoral caregivers. Care teams are established based on the number of people who need to be served; the behavior management team both oversees the care teams and monitors the progress made toward implementing appropriate interventions for residents.

Education is fundamental to the success of the program, and the education process is ongoing. Innovative techniques provide caregivers with the basic assessment tools needed to evaluate their residents' behaviors and, in the process, caregivers develop a partnership of care that encourages one another. Care that develops a relationship with each individual resident, results in interventions that are proactive and person-centered.

As the staff becomes more familiar with a person-centered behavior approach, respected and protected relationships develop between residents and their team of caregivers. The team approach makes it possible to distinguish individual preferences, expectations and needs and to provide residents with an optimal standard of care. Caregivers, too, benefit from a behavior management team approach, because the knowledge gathered and shared results in a better implementation of proactive strategies, which in turn reduces problem behaviors.

For example, John is a resident whose dementia symptoms include wandering. By paying careful attention to John and sharing observations among staff who work with him at different times, caregivers can see that John's behavior follows a pattern — first he gets restless, then anxious, then he heads for a door, intent on getting outside to "escape." Even if they can't isolate a triggering event for John's stress, staff can be proactive based on his pattern of behavior, such as by taking him outdoors for a walk at his first signs of restlessness, thereby intervening before his stress level increases to the point he tries to escape.

Using proactive management to diminish problem behaviors like John's helps lower resident stress, but it reduces caregiver stress, too. The result of both is to produce a higher standard of care. Staff members are able to treat each resident in their care as a person, not as a task to be completed, thus continue to develop closer relationships with residents, carry out the healing mission of Jesus and see Him in each person in their care.

Sr. M. PETER LILLIAN DiMARIA, O.Carm., is director of the Avila Institute of Gerontology, Germantown, N.Y. The Avila Institute of Gerontology is the educational arm of the Carmelite Sisters for the Aged and Infirm.

ALFRED W. NORWOOD is a behavior specialist who works with Avila Institute serving elders experiencing cognitive impairment and their caregivers.

NOTES

- Marianne Smith et al., "History, Development, and Future of the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold: A Conceptual Model for Dementia Care," Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52, no. 10 (2004): 1755-60.

- Brenda L. Plassman et al., "Prevalence of Dementia in the United States: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study,"Neuroepidemiology 29, (2007): 25-32.

- Sytse Zuidema et al., "Prevalence and Predictors of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Cognitively Impaired Nursing Home Patients," Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 20, no. 1 (2007): 41-49.

- Hans K. Normann et al., "People with Severe Dementia Exhibit Episodes of Lucidity. A Population-Based Study," Journal of Clinical Nursing 15, no. 11 (2006): 1413-17.

- Marianne Smith et al., "Application of the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) Model across the Continuum of Care," Nursing Clinics of North America, 41, no. 1 (2006): 57-81.

- Sytse Zuidema et al., "Predictors of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms."