BY: JOHN GLASER, S.T.D., and DEBORAH A. PROCTOR

"The contemplative gaze renders the whole world sacramental." — Sr. Elizabeth Johnson, CSJ

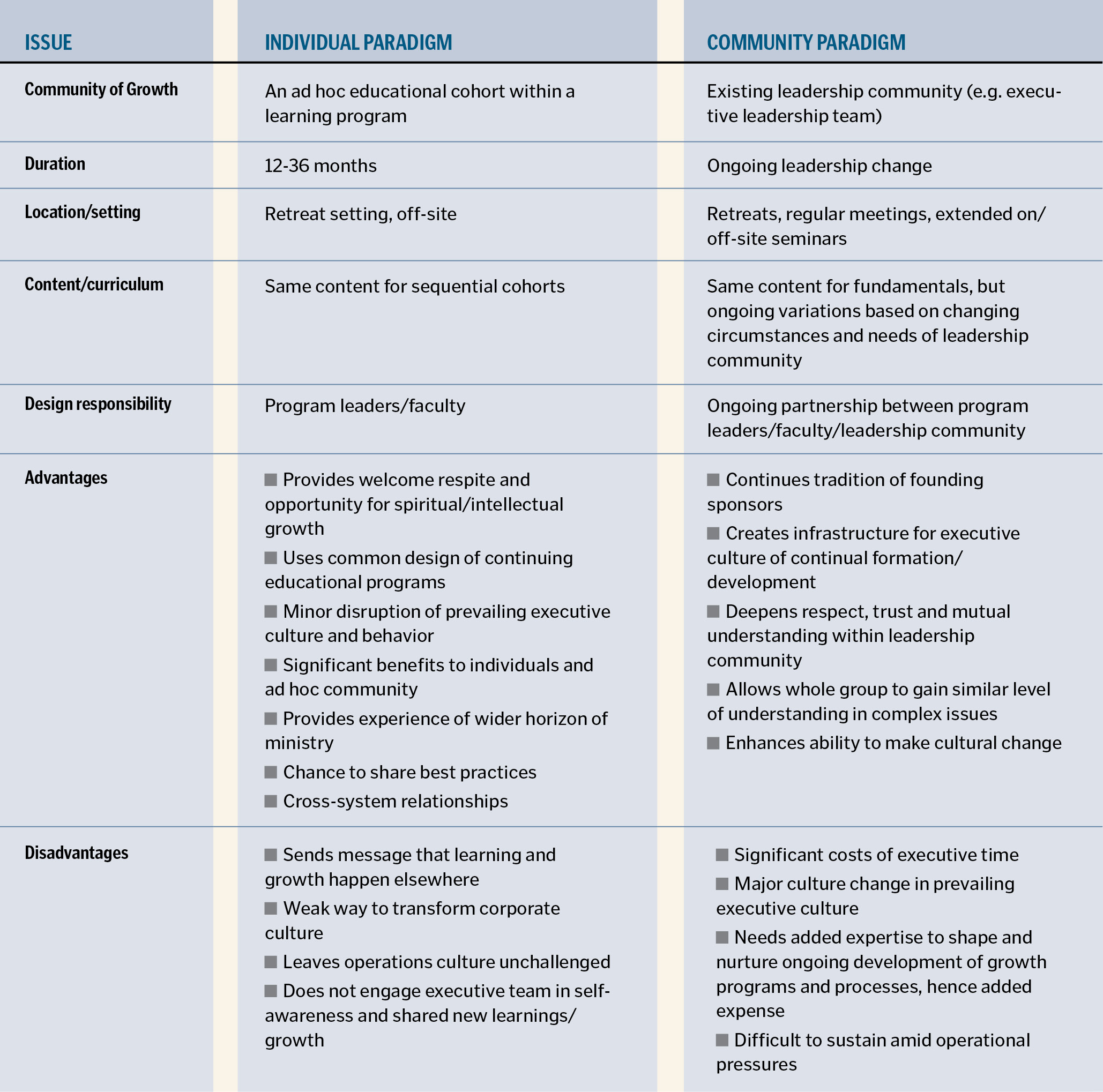

Under the prevalent model of leadership formation in Catholic health care — we would even say the default model — individual executives are chosen from a given health care organization and invited to participate with executives from their own system, or across systems, in a learning and development cohort. Sessions take place outside the executives' usual environments, generally in a retreat-like setting.

However effectively this individual-centered model might have served participants, we believe it is time for a different one. We would like to propose a model that, in our experience, would better contribute to a senior leadership culture of continuous formation and assure lifelong learning and development among leaders. We believe such a model, which we have labeled the community-centered model, is more in keeping with the formation culture of the religious organizations that founded Catholic health organizations and will help foster a deeper formation culture in the values Catholic health care espouses.

The community-centered model is based on helping lay leaders develop a spirituality of contemplation in action, a spirituality based on merging religious values with all of life, including work.

SOME HISTORY

Contemplation in action is the practice of ongoing prayer, formation and learning that continually and over a lifetime shapes and feeds service to one's neighbor, deepening and sustaining it as Christ's ministry of compassionate service. In the history of Catholicism, the spirituality now known as contemplation in action evolved as men and women religious began moving out of traditional place-based monasteries and convents into new, active ministries. As active orders joined their respective civic communities in presence and service, immersing themselves in the turbulent world of human needs and contending with secular social forces, a new spirituality emerged: one aimed at unifying this new way of life with a deeply-rooted, Gospel-based vision. As they engaged in extensive and sometimes exhausting works of service, members of these active religious orders sought to become spiritual leaven, continually reflecting on the Gospel in light of the cultures in which they lived and the work they were called to do. This spirituality is our heritage in our health care ministries. It is one we are called to cherish and nurture as an essential dimension of our Catholic ministry identity.

THE URGENT NEED

Many factors point to an urgent need for deepening our formation and development culture. Let's look at two of them.

One factor is the growing number of lay leaders in health care ministry. This is no mere pragmatism — a filling of gaps left by a diminishing number of vowed religious. It is the work of the Spirit in history. But this emergence of the laity requires a corresponding development of spirituality and work culture, one that enables lay leaders to continually deepen their understanding of the essential dimensions of a calling to ministry and of the Gospel basis of the ministry to which they are called. If dedicated religious of 16th century France needed ongoing formation and lifelong learning to track the true north of ministry, dedicated lay leaders in today's complex and turbulent world need it even more.

Another factor is the extent to which Catholic health care institutions must comply with problematic structures of American health care. Because our present system has been cobbled together over six decades by a variety of interest groups — disparate forces tugging in different directions without an overall vision, consensual value priorities or a unified and accountable leadership — the structures that comprise the U.S. health care system, including Catholic structures, are honeycombed with irrationality and injustices.1

Prominent economists have spoken strongly about these problems. In the blunt words of Henry J. Aaron, health care expert at the Brookings Institution, U.S. health care is "an administrative monstrosity, a truly bizarre melange of thousands of payers with payment systems that differ for no socially beneficial reasons."2

Uwe E. Reinhardt of Princeton University has lamented the way in which this convoluted and disorganized system leads to wasteful, bloated contracting and billing departments.3

Honoring both the short-term practical need to conform to such unjust systems and the long-term ethical imperative to confront and transform them requires that executive teams have awareness, time, space, tools and skills for such discernment and advocacy. Such conflicts between ministry priorities and the coercive structures of U.S. health care abound.

Both of these factors — growing lay leadership and intense pressures for conformity to incoherent and unjust structures — call us to develop a robust culture of formation and reflection for our senior leaders.

THE NEW MODEL

The rationale for our argument that a community-centered formation model could better meet the needs of the ministry today is based on two assertions.

The first is that existing communities of responsibility (e.g., senior executive teams) are the communities in which growth and development should take place. In lieu of sending individuals elsewhere for formation and development (in what we called the individual-centered model), organizations in the ministry are better served if the resources of the formation program, including experts and content, come into the ongoing life of existing leadership communities and partner with them in shaping a continuous commitment to growth and development.

Our second assertion is that the life and culture of an executive team now must include consistent, substantial and ongoing formation and development. As in the tradition of our religious founders, formation of our lay health care leaders must be far more than a program or curriculum inserted into the life of a leader. Rather, it must be an introduction to, continuing support for and ongoing immersion in a spirituality of contemplation in action.

Like its individual-centered counterpart, a community-centered formation program will at some points require a retreat setting when the content requires sustained time, substantial facilitation and special expertise. At other points, the content can be well handled by shared reading and reflection as part of routine leadership meetings. Some of the content will be universal for all ministries of the church; some of it specific to the history of the specific ministry and its founders; some of it idiosyncratic to this institution at this point in history. Making such design decisions in partnership with the leadership team is a major responsibility of the formation/development program.

PROBLEMS WITH THE DEFAULT MODEL

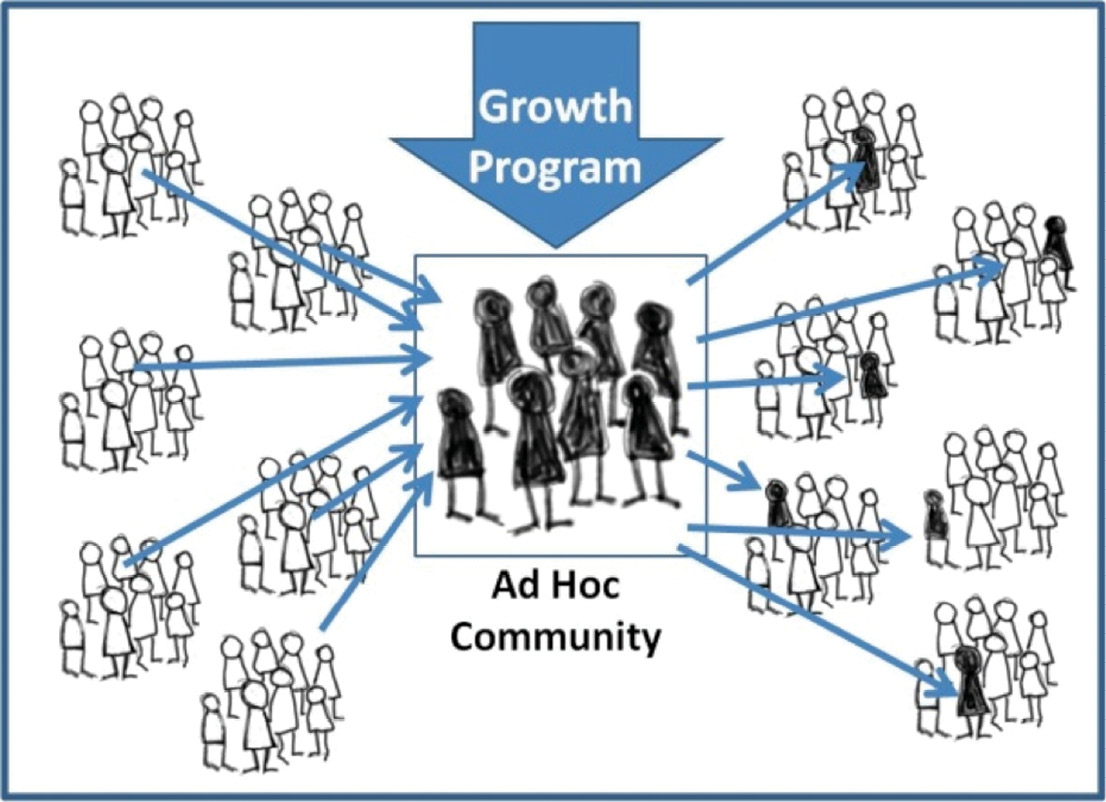

Leadership formation and development programs have been increasing across the Catholic health care ministry in recent years. According to a CHA survey, over 60 percent of Catholic hospitals belong to systems with such programs, most of them conforming to what we describe as the individual-centered model. By that, we mean that individuals are selected from various organizations and/or communities of responsibility and they join other individuals to form a new, ad hoc learning and development cohort. This learning cohort meets monthly or bimonthly for 12 to 36 months in a retreat setting and engages in a series of learning modules and community-building processes. After this developmental experience, individuals return to their original communities of responsibility, taking their learning back into their leadership role.

This model has proven to be of significant value.4 We would argue, however, that although the individual-centered model is good, it is not good enough. We believe a more powerful organizational intervention is needed — one that better matches our heritage and does justice to the rapid expansion of lay leadership and the growing pressures from forces hostile to health care as a faith-based ministry.

FORMATION AND DEVELOPMENT

In discussions around leadership growth, a distinction is often emphasized between leadership development and leadership formation. For example, John Mudd, senior vice president for mission leadership, Providence Health & Services in Renton, Wash., notes: "leadership development is typically focused on … two dimensions — knowledge and skill — helping the leader advance in areas like planning, finance, operations and human resources. … Formation is designed to bring into sharper focus the ministry's mission, vision and values, and to consider the alignment between these dimensions as they are experienced in the life of the ministry and the life of the leader."5 (emphasis added)

We believe such a distinction is valid and vital in the ongoing defining and designing of a program. But relative to the concerns of this article, such a distinction is not of central importance because we believe these dimensions of growth — development and formation — are both best nested in the life of existing leadership communities.

STRENGTHS OF THE PROPOSED MODEL

To demonstrate the power of the community learning model, consider the instance of a merger between two health care organizations. As many health care leaders know, there is usually a well defined "check-list" for evaluating a merger partner. Most of these items are discussed as issues of compliance with a limited view of the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services. Organizations often check off the boxes ascertaining there are no major issues that will cause questions with diocesan bishops. A team that has engaged in community-centered formation and development is likely to approach this process very differently. From the inception of a growth strategy to the details of a particular merger or acquisition opportunity, the senior team should be fully engaged in ministry discussions. Questions of how the opportunity serves the common good of the communities being served, how it contributes to extending the ministry and whether it solves or poses justice issues should be a critical part of initial discussions. From our experience, where the individual-centered formation model has been employed, a senior leadership team may have one or two individuals who raise these critical questions, but the senior leadership team overall shared understanding and, as a result, the discussion is often cursory.

In a recent discussion among leaders within our organization, we were considering an opportunity for collaborative rather than competitive behavior in relation to another hospital in our area. It was rewarding to see our team start with the questions of the common good for the community we serve, rather than with the financial implications. Without a shared understanding, this discussion could have served to divide rather than to unite.

One of the authors spent a year with a hospital executive team experimenting with the community-centered model. Some elements that contributed to its success were:

- It was formally established. We all committed to the effort and spelled out what it would ask of us.

- It was substantial. We agreed to take a full day off-site once a month and dedicate our time to formation/development.

- It was sacred. We agreed to treat this as equivalent to the importance of a board meeting.

- It was planned and facilitated. Two staff and a consultant analyzed the sessions and planned the content and sequencing in collaboration with the executive team. Staff and consultant provided facilitation.

- The team that participated in this model identified a number of significant associated strengths, including the following:

- It decidedly deepened mutual understanding of and appreciation for one another on the team.

- It established a foundation for greater respect, trust and open, risk-taking communication.

- It provided for shared exploration of the history and meaning of each participant's call to Catholic health care.

- It gave time and space for the whole team to achieve a similar level of understanding of a variety of issues, including the history and tradition of sponsors; the role of for-profit ventures in ministry; incorporating values into decision-making processes; understanding organized labor in the context of Catholic social teaching.

- It surfaced and addressed weaknesses in a team's interaction habits and style and addressed organizational problems.

- It celebrated team and individual strengths and gifts.

- It provided greater self-awareness both for groups and for individuals.

- It provided a predictable time and space to raise important issues that routinely had little chance to surface. It also promoted multi-session explorations and pursuit of unfinished business.

BARRIERS TO A MODEL SHIFT

While we believe that moving from the present individual-centered paradigm to the community-centered one is extremely important, we know it will not be simple, easy or quick.

Perhaps the biggest barrier will be the experienced benefits of the individual-centered programs. Another weighty factor is this: "possession is nine-tenths of the law." There are programs, persons, departments, budgets and calendars associated with the individual-centered model already in place. In addition, the community-centered model demands substantial resources — significant time and energy of senior executives and funds to provide the support and facilitation that executive teams will need for implementation. This is change of notable weight and should be recognized as such. Cultural change of this kind is clearly difficult, even when patently necessary.

CATHOLIC IDENTITY AND MISSION INTEGRATION

Catholic health care has boldly faced and made significant progress in identifying essentials of Catholic identity and developing key elements of mission integration. We believe that the issue we raise above — building a culture of contemplation in action that is dedicated to ongoing formation and lifelong learning — is a growing edge of mission integration and Catholic identity. Our proposal, unpacked above, seems to us a difficult but indispensable move toward more robust Catholic identity and mission integration.

DEBORAH A. PROCTOR is president and CEO of St. Joseph Health System, Orange, Calif.

JOHN GLASER is scholar in residence at St. Joseph Health System, Orange, Calif.

NOTES

- Daniel Callahan, False Hopes: Why America's Quest for Perfect Health Is a Recipe for Failure (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998); Daniel Callahan and Sherwin B. Nuland, "The Quagmire: How American Medicine is Destroying Itself," The New Republic ( June 9, 2011): 16-19.

- Robert Kuttner,"The American Health Care System: Wall Street and Health Care," New England Journal of Medicine, 340, no. 8, (Feb. 25, 1999): 664-668. John W. Glaser, "Catholic Health Ministry: Fruit on the Diseased Tree of U.S. Health Care," Health Care Ethics USA, 15, no. 1 (2007): 1-4.

- Uwe Reinhardt, "The Pricing of U.S. Hospital Services: Chaos Behind a Veil of Secrecy," Health Affairs, 25, no. 1, (2006): 59.

- Laurence O'Connell, John Shea, "Ministry Leadership Formation: Engaging with Leaders," Health Progress, 90, no. 5 (September-October, 2009): 34-39.

- John O. Mudd, "When Knowledge and Skill Aren't Enough: Leadership Formation Takes Leaders to New Levels," Health Progress, 90, no. 5 (September-October 2009): 26-32.