BY: SR. ROSEMARY DONLEY, PhD, APRN, FAAN

History tells us Catholic hospitals were started in local communities by religious women and men as works of mercy, dedicated to overcoming disease, malnutrition and the effects of poverty, illiteracy, stigma and racism among immigrant populations. All those conditions — especially access to person-centered care — are determinants of health.

The impact of social, economic and physical environments on health status was something the Catholic health ministry recognized from the very beginning. As the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts it now, it takes more than sophisticated medical and expert nursing care to manage chronic disease, particularly if the chronically ill person lacks a safe place to live and exercise, healthy food, a stable income and support systems.1 It takes a community that is listening and working collaboratively together to build and sustain healthy neighborhoods.

In healthy communities, people talk with each other, share resources fairly and collaborate because no one is an outsider or a stranger. In good communities, people have jobs that pay living wages, experience food security, attend safe day care, good schools and stimulating senior centers and enjoy attractive places to live, relax and play. Building good communities challenges mind, body and spirit; it provides the framework for good health.

For the Catholic health care ministry, nurturing healthy communities remains a calling, though perhaps the terminology has changed. Indeed, the ministry often talks about "community benefit" as a program to exemplify, validate and justify its not-for-profit, tax-exempt status. However in contemporary health care, and certainly in Catholic health care, community benefit has a richer meaning. It speaks to acting out principles of social justice: respecting the dignity of all persons; standing in solidarity with the poor and underserved; and participating and partnering with community residents and other community-based civic, church and private organizations in planning and delivering a wide range of services that affect health status and personal dignity.

HEALTH POLICY TRANSITIONS

The passage of Medicare in 1965 gave fiscal and professional validation to the importance of hospitals in the care of ill persons. Hospitals responded to this vote of confidence by developing complex technology and expanded systems of care. It did not take long for policymakers and providers to see that admitting a person to a hospital was an expensive clinical decision. It also is well documented that misuse of emergency rooms and frequent admission and readmission to hospitals are the most expensive ways to deliver health care.

The transition of diagnostic and primary health services, and even minor surgery, into the community has been driven by a desire to lower the cost of health care.2 In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan supported several initiatives to redirect care back into the community. In 1981, The Omnibus Reconciliation Act created a Medicaid waiver program that allowed states to provide and pay for home and community-based care for certain populations.3 The Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act in 1982, along with the Prospective Payment Act in 1993, changed the way that Medicare paid hospitals by creating a new payment framework to replace fee-for-service and retrospective reimbursement.

However, diagnostic related groupings (DRGs) and prospective payment systems had a negative impact on the flow of dollars into the hospitals' revenue streams. Costs continued to rise, although the hospital landscape and acute care practice patterns changed dramatically by delaying admissions, reducing the length of hospital stays, creating more efficient discharge planning systems and developing more ambulatory centers. Still, community-based care systems did not expand to assume health care services as public and private sector hospitals closed, merged, developed more specialized inpatient services and eliminated hospital beds.

AFFORDABLE CARE ACT

The Affordable Care Act is the most recent law to encourage community-based care. Passed in 2010, the ACA provided funds and encouragement for primary care providers, especially nurse practitioners and physician assistants, to work in community-based teams and manage chronic illnesses. The law also created the National Prevention Council, calling for a prevention strategy to improve quality of care and provide coverage options for uninsured people.

Case management and accountable care organizations are other ACA attempts to coordinate care delivery and expand ambulatory centers where people, especially those who are poor and underinsured, can find primary and prevention services in stable medical or health homes.4 In fact, today, clinicians work not only in community-based health centers, traditional ambulatory hospital-based clinics and home care programs, they deliver and manage care in supermarkets, shopping malls and pharmacies. Health services in these new community settings are convenient, accessible and less expensive. They often are the settings of choice for busy people who seek primary care for infections, upset stomachs, rashes and abrasions. Many of these mall or store-based clinics also provide hearing and vision screening and offer a wide range of immunizations.

Yet the two systems — acute care and community care — remain separated from each other. In an age when collaboration and coordination of care are valued, these modalities of care are not linked to each other or to providers in any meaningful, patient-centered way. The preventive and episodic care offered in community settings stands alone. Information about a person's health problems, treatment or outcomes is not usually reported to his or her primary care providers or integrated into electronic health or insurance records.

As a consequence, treatments at these inexpensive, community-based health care centers are not recorded or recognized as a formal part of people's health and illness experiences. Just as important, providers in grocery store clinics — even if they were to try — likely would find it hard to communicate about a patient with primary care networks, providers or health systems because of schedules, network access and privacy concerns.

America's renewed interest in primary care and team-based practices in communities, especially with chronically ill individuals, has been driven by the stubbornly high cost of acute care, the aging population and the persistent interest of medical students in specialty practices despite many federal and state efforts to encourage primary care residencies.5 The Department of Health and Human Services identifies the strengthening of health care as its No. 1 strategic goal. Specifically it links investment and integration of community-based health care to positive health outcomes, continuity of care, better preventive health care, greater access to primary care, and earlier diagnosis and treatment of disease.6

These benefits, however, cannot be realized unless community-based centers and practices are seen as essential parts of a continuum of care. Currently there are more disincentives than incentives for supermarkets, pharmacies and unaffiliated and safety-net clinics to invest in the technology and training necessary to access and enter information into patients' medical/health records. Often the local emergency room becomes the place where the patient seeks follow-up care if the problem that brought him to the clinic remains unresolved. Lack of coordination, communication and integration of health information results in a situation where the value-added component of community-based services is yet to be rigorously tested.

As has been noted, most primary and preventive care has been delivered in physicians' offices or clinics in the United States. Today, these venues have been significantly expanded. However, primary and preventive care are not the same. Douglas Elmendorf, director of the Congressional Budget Office, noted that different types of preventive care have different effects on spending.7 Although he is seeing prevention through a narrow lens of short-term cost reduction, his point of view needs to be taken seriously.

Measurement of outcomes and cost benefit of preventive services — other than immunizations — is not easy. More measurable are the outcomes and cost of monitoring and initiating early interventions in disease states, in this case chronic disease states. However, outcomes remain elusive, because unlike in the United Kingdom and some countries in Western Europe, there is no established pattern of communication, oversight and intervention among providers, community settings, acute-care hospitals and rehabilitation units.

It also seems that while the rediscovery of community-based care is a hopeful sign, a very important strength of community-based care is being overlooked. Communities are homes, not hospitals or low-cost primary care systems. They are places where people live, work, raise their families, visit their friends and worship.

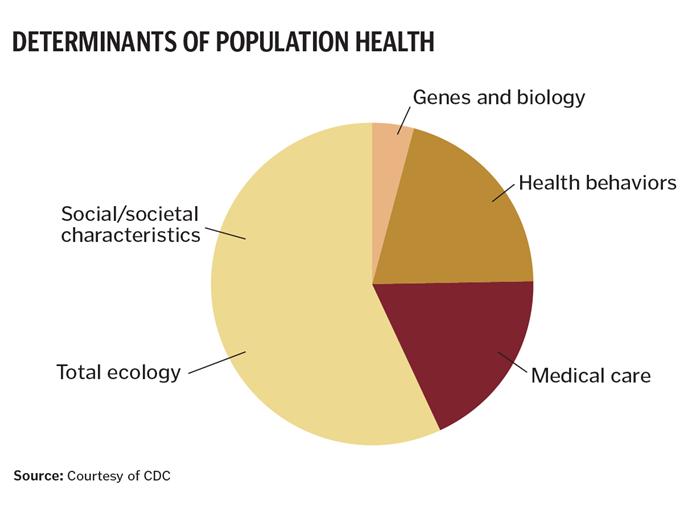

In its Determinants of Health model, the Centers for Disease Control estimates that genes, biology and health behaviors, grouped together, influence about 25 percent of population health.8 Social and economic life also influences individual behaviors contributing to the patterning of health, disease and illness, and they affect health equity and social advantage or disadvantage. National and global evidence links better health with: higher incomes and social status, more education, access to safe water and clear air, healthy workplaces, safe housing, satisfying work, supportive social networks, good genes, responsible personal behavior and enhanced coping skills.9 These health indicators form the building blocks of healthy communities and healthy people.

Linking what is known about communities to the health care delivery system only can improve the health status of people. The strengths and weaknesses of the local communities are well known to safety-net providers, many of whom are in Catholic health care. Prior to health system development, the majority of community hospitals were under Catholic auspices.

The work of building healthy communities is challenging. It calls for the vision and the missionary spirit of one of Catholic health care's recognized pioneers, Mother Joseph Pariseau, the founder of the Sisters of Charity of Providence. In the 19th century, she worked with others to build 11 hospitals up and down the West Coast.

If she and the other founders of the Catholic health system were with us today, they would be working actively with their hospitals, nursing homes and systems as well as with churches, schools and community-based agencies to create models of comprehensive community-based care directed to the common good.

Are we listening to their voices?

SR. ROSEMARY DONLEY is professor of nursing and the Jacques Laval Chair for Justice for Vulnerable Populations, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh.

NOTES- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Social Determinants of Health." Retrieved from: www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/FAQ.html.

- MaryBeth Musumeci and Erica L. Reaves, Medicaid Beneficiaries Who Need Home and Community-Based Services: Supporting Independent Living and Community Integration (Menlo Park, California: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014). kff.org/report-section/medicaid-beneficiaries-who-need-home-and-community-based-services-introduction-8568/.

- Nancy A. Miller, "Medicaid 2176 Home and Community-Based Care Waivers: The First Ten Years," Health Affairs 11, no. 4 (November 1992): 162.

- Ronald E. Aubert et al., "Nurse Case Management to Improve Glycemic Control in Diabetic Patients in a Health Maintenance Organization: A Randomized, Controlled Trial," Annals of Internal Medicine 129, no. 8, (Oct. 15, 1998): 605-12.

- Lewis G. Sandy et al., "The Political Economy of U.S. Primary Care," Health Affairs, 28, no. 4, (July-August 2009): 1136-45.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, "Strategic Goal 1: Strengthen Health Care." Retrieved from: www.hhs.gov/strategic-plan/goal1.html.

- Matthew DoBias, "Preventive, Wellness Care Could Drive Up Costs: CBO," Modern Healthcare, (Aug. 10, 2009). Retrieved from: www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20090810/NEWS/308109947/.

- CDC, "Social Determinants of Health."

- Lyla M. Hernandez and Dan G. Blazer, eds., Genes, Behavior, and the Social Environment: Moving Beyond the Nature/ Nurture Debate (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2006).