BY: CELESTE DE SCHRYVER MUELLER, D.Min.

"It needs to be practical!" is a universal cry from leaders to those responsible for providing formation in health care settings. Simultaneously, health care organizations frequently name "knowledge of the theological tradition that sustains Catholic health care" as a formation goal. Assuring that formation is practical may seem to preclude providing substantive theology, but the two aren't either/or, or even a two-track process. Implicit in both goals is a unifying desire for meaning: personal meaning, meaning in one's work, meaning in the tradition.

This article offers three strategies that can help formation programs engage both substantive theology and practical application in ways that are meaningful to participants. They invite personal transformation for the sake of advancing the mission of Catholic health care. As a formation facilitator in both the two-year executive formation program and the one-year management formation program at Ascension Health, St. Louis, I have had the opportunity to help develop these strategies and to witness their impact:

- Locate formation within a unified matrix or model

- Use reflective practice as a learning method

- Make theological content accessible as a practical resource through a logical structure

These strategies orient formation toward an integrated and empowered spirituality. They can remain a consistent core as formation processes are adapted to various audiences: executives, managers, associates, board members and sponsors.

A MATRIX FOR FORMATION

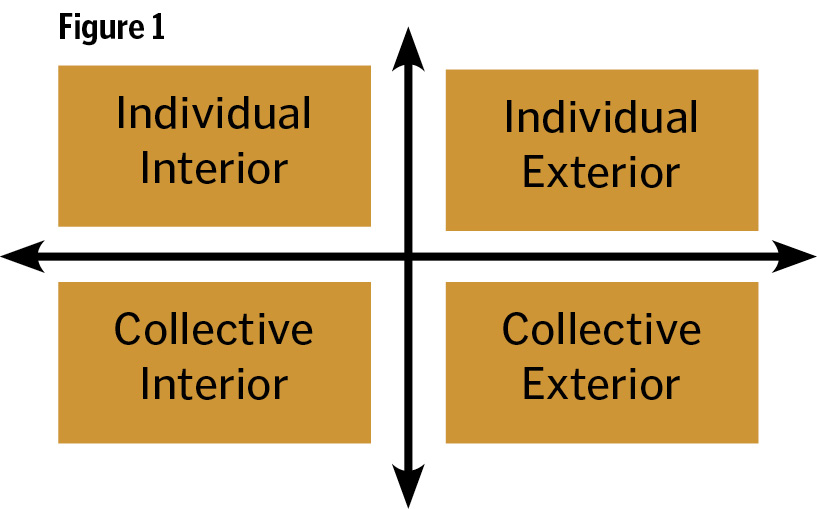

The philosophy of author Ken Wilber1 articulates an integral vision that provides a matrix for integrating the various components of formation. A grid of four quadrants (see Figure 1) offers a "sketch of an integral map of human possibilities"2 that he explores through examples from many fields of endeavor including medicine, business, education and politics. Adapted here in its simplest form,3 this grid identifies four dimensions of human experience to which a comprehensively integrated formation process would — I'd even say should — attend.

The upper tier of the matrix reminds us that the mostly invisible interior life of individuals exists in a dynamic unity with the more visible exterior life of actions and behavior. It is important to explore both interior and exterior dimensions of experience because interior values, dispositions and attitudes both shape one's behaviors and are shaped by one's behaviors. One's individual interior life, often ignored in standard management training and leadership development, is the locus of personal meaning, and ultimately it drives behavior. Unexamined values, dispositions and attitudes can sabotage individual behaviors organizations desire.

The upper tier of the grid mirrors the reality of the individual, while affirming that individuals always exist as persons in community. The lower tier highlights the dynamic relationship between the mostly invisible interior life or culture of groups and organizations, and the exterior life of groups and organizations, which includes established policies, processes and business systems.

Attending to both of those quadrants is critical because unstated and unexamined cultural expectations have such a powerful influence on the ability of organizations to carry out processes that will advance the mission. Conversely, becoming more aware of the ways that an established culture is genuinely mission-centered can streamline discernment and decision-making about communal practices, processes and systems.

Every person engaged in formation has experiences in each of the four quadrants. Formation leaders can use the matrix to develop processes that invite participants to increased awareness of and responsibility for each dimension of their experience. Formation participants can use the matrix to locate themselves within the breadth of their experience, to recognize influences on them and ways that they can influence the organization, to recognize points of personal and organizational misalignment and lack of integrity and to become more effective instruments and agents of integrity and alignment.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE AS A MODE OF LEARNING

Since Donald Schön introduced the phrase in his book The Reflective Practitioner,4 educators have widely affirmed the positive impact of the "practice-reflection dynamic." Recent literature in the neuroscience of learning further affirms that practice and reflection are essential to learning that is both persistent and transformative.5 Despite the clear consensus about the critical value of practice, the primary mode of learning, even in formation programs, continues to be audio-visual presentations to mostly passive audiences.

Some programs entirely separate presentations of theological content from the formation participants' personal and professional practices. Often in this case, the presentations are criticized as "too academic" or "too heady." My experience suggests that the criticism is misplaced. Professionals in health care are highly intelligent and motivated; they are hungry for substantive theology and spirituality. The problem is that without connections to participants' own experiences, and without opportunities to experience the significance of theological and spiritual concepts in their own practices, participants cannot make meaning out of the concepts they are receiving.

Beginning a formation event with reflection on one's own experience or on specific cases (the exterior side of the formation matrix) can reveal and generate insights about individuals' interior life, their personal dispositions and values. Making these connections, in turn, opens a path of connection to theology and spirituality that can be introduced as resources to help assess practice, expand understanding and deepen core commitments.

Storytelling6 and guiding questions7 are reflective tools that respectively foster deeper awareness of personal and organizational practices. I have seen reflections on practices open meaningful connections for participants to even abstract theological concepts such as revelation and grace. These, in turn, allowed participants to see deeper layers of meaning in their experiences and, in some cases, to reorient their practices.

When theological concepts are more practically oriented, the opportunities to begin with practice are more obvious. Formation in Catholic social teachings, for example, can begin with reflection on a participant's personal actions or on current organizational policies, or it can begin with an invitation to a practice that might allow participants to see the world through the eyes of the most vulnerable. From the perspective of those reflections, Catholic social teachings become genuine resources for personal and organizational action rather than simply good ideas.

The Ascension Health Management Formation Program, under the direction of Dennis Winschel, uses the method of reflective practice. This program offers management skills that are grounded in a theological vision; the formation begins from the perspective of skill building. After a recent management formation retreat, participants were asked to practice three things regularly until the next retreat and to report briefly on what they experienced. They practiced coherent listening, giving appreciative feedback and they held a personal symbol of another participant. When the group gathered for the next retreat, the experiences they related opened a powerful connection to the idea of the communion we share as humans and as the community of Catholic health care, to the idea of the abiding presence of God and to God's promise, "I will be with you."

The connections between their practice and the faith tradition, made explicit in their reflection and discussions, yielded a rich understanding of the tradition and inspired a deeper commitment to the management skills they were learning. They could see that the ways they managed their associates was a direct expression of the mission and directly connected to the healing mission of Jesus. This example is striking to me because the impact I witnessed was disproportionately greater than the time invested in presentations, practice or reflection. Reflective practice is a most efficient path to transformation and does not need to sacrifice substance.

LOGIC FOR THE THEOLOGICAL CONTENT OF FORMATION

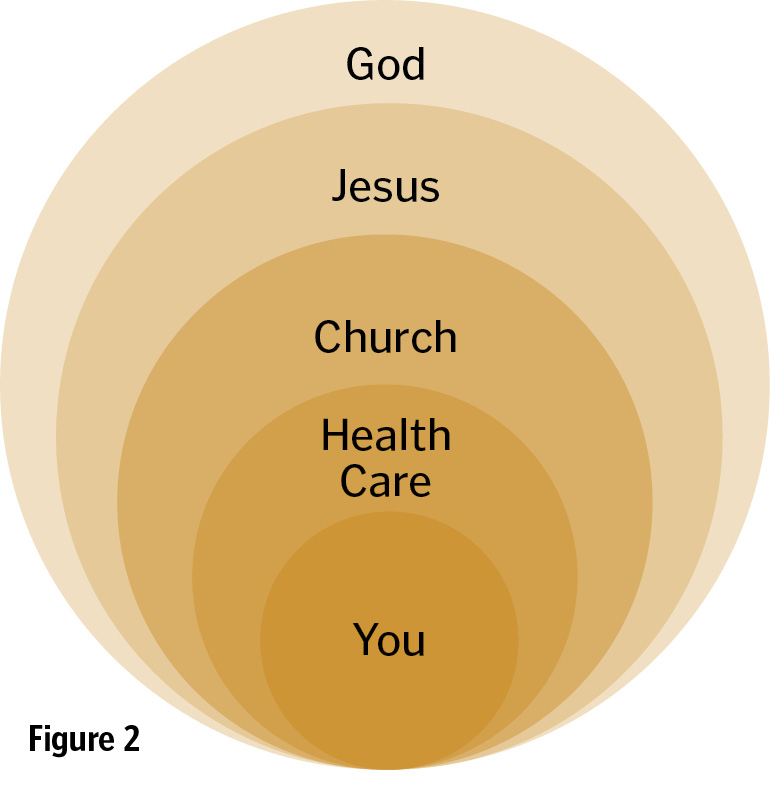

Discussions abound regarding what constitutes the essential theological content for ministry formation. Aspects of the theological tradition that have potential significance for health care are even more abundant. Whatever particular elements are selected, these concentric circles (see Figure 2) present a logic that helps to organize the content in ways that make the tradition accessible to participants and applicable to their practical needs. Moving through this framework with the Trinitarian God as the starting point, formation participants see that God's mission has been revealed and carried out in an unfolding path through history. They see that God's mission leads directly to their work in Catholic health care.

Using this framework at a recent management formation retreat, I was able to highlight connections for a group of managers between the specific work of managing change to the concept of the Reign of God. I followed this sequence: Reflection on their vocation as managers, which is rooted in the gift and task of the mission to provide "spiritually centered holistic care," which is an expression of the healing ministry of Jesus, which is an embodiment of the vision of the Reign of God. I was startled by the number of participants who expressed gratitude and appreciation for the meaningful connections.

Whether in extended course modules or in very brief formation moments, this framework helps participants to keep the big picture of health care ministry in mind. When associates, leaders or board members are invited to ask: "Who will I be and what will I do in my service of Catholic health care?" this framework helps them to see that they represent and are supported by a series of wider and wider realities articulated in Catholic theological tradition. They can see that as individuals, they serve within the embrace of the community of Catholic health care, which exists within the wider embrace of the church, which exists as a community "in Jesus Christ," who exists as the embodiment of the Divine Presence.

The recognition that these realities are gifts to each person working in Catholic health care and are given for the sake of the mission is most significant for formation participants. They realize, for example, that the heritage of Catholic health care; the witness of the founders; the communion and mission of the church; the Incarnation, ministry of Jesus and Paschal mystery; the Trinitarian communion of mutual, self-giving love; the creative and unpredictable power of the Spirit; are resources for their own personal growth and their actions as agents of the mission. Whether experienced as one's own lived faith or appreciated as ideas witnessed in the life and history of the Christian community, these realities are resources that belong to all those entrusted with the mission of Catholic health care.

Engaging the multiple dimensions of our human experience through reflective practices that allow the riches of the tradition to be received and used as resources can promote one's spiritual growth and empower one's service in Catholic health care. I am convinced that using the strategies described here can bear fruit in both personal and organizational transformation. I offer this conviction with an invitation to continuing conversation, and I eagerly hope that readers will share their own formation experiences.

CELESTE DE SCHRYVER MUELLER consults with organizations on topics of leadership formation, mission and Catholic identity. She teaches practical theology as an adjunct professor at Aquinas Institute of Theology, St. Louis, and is in demand as a facilitator of theological and spiritual formation. Contact her at [email protected].

NOTES

- I am greatly indebted to Dennis Winschel and Bill Brinkmann at Ascension Health, St. Louis, for introducing me to the work of Ken Wilber.

- Ken Wilber, A Theory of Everything, (Boston: Shambhala, 2001) 43. This is just one of the many works in which Wilber explores his integral vision.

- Wilber, 70.

- Donald Schön, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (New York: Basic Books, 1984).

- James E. Zull, The Art of Changing the Brain. (Sterling, Va.: Stylus Publishing, 2002).

- Celeste DeSchryver Mueller, "Create Sacred Space with Stories: Storytelling as a Formation Tool and Spiritual Practice," Health Progress (November-December 2010): 17-21.

- Celeste DeSchryver Mueller, "Theology Goes to Work: Applying Theological Reflection to the Business of the Day," Health Progress (July-August 2009): 37-43.

Copyright © 2011 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.