SUSAN K. BARNETT

Founder of Faiths for Safe Water

I recently had surgery to restore some hearing loss. It was an outpatient procedure but required general anesthesia. Though I found myself in post-op recovery at a top hospital in New York City, where I live, the picture I couldn't get out of my mind was of something quite different. I work on issues of access to water and sanitation and as I felt my fresh sheets and took notice of the clean bathrooms and persistent handwashing by staff, I couldn't help but revisit the hospitals and health clinics I've seen where clean and safe health care is impossible.

I've seen donkeys making 20 trips a day, carting water from a river where animals drink and defecate, to a rural hospital in Ethiopia because that is the only water source. I won't forget the small pink bucket that was one half of a health center's entire "water system" in rural Nepal. In an area endemic for typhoid and malaria, I've watched medical staff forced to go outside to wash their hands in water containers that are a breeding ground for disease-carrying mosquitoes. I've seen more broken faucets and sinks than I can count, open defecation on health care facility property due to the lack of functional toilets and outhouses, and waste pits filled to the brim with all manner of medical waste.

This problem is widespread across low- and middle-income countries. According to the 2020 WHO/UNICEF Global Progress Report, one in four health care facilities worldwide lacks adequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).1 Isolating the 47 low-resource countries, 50% of health care facilities lack water on site, and sanitation is even worse, with 63% of facilities failing to provide adequate toilets. Doctors and nurses working at 30% of these health care facilities cannot wash their hands at points of patient care. Nearly 2 billion people rely on these facilities, which cannot comply with the most basic safe care standards.

The lack of access to clean water, toilets, hygiene and waste management in health care facilities is its own kind of global health pandemic. Quality health care is impossible without WASH, and poor-quality health care is costly. Lost productivity totals $1.4 to $1.6 trillion per year.2 The human costs are incalculable: Infection prevention control is impossible. Antibiotic resistance increases worldwide. Response to COVID-19 has been deficient, and Ebola has killed medical staff in tragically high numbers.

Faith-based organizations are critical to global health. Around the world, faith-based networks provide health care where there might otherwise be none, operating without discrimination to religion or nationality. Yet far too often, faith-based facilities also operate without WASH.

The reasons for the lack of WASH share common themes. Sometimes the problem is the absence of infrastructure or infrastructure that was never completed; sometimes infrastructure is crumbling due to the lack of training and maintenance; often there's no budget, and staff do the best they can. With good intentions, faith communities and nonprofits have sometimes delivered wells and pumps without a plan to maintain them after they leave.

As the single largest unified source of health care worldwide, the Catholic Church's interest in WASH can be transformative. The Vatican has taken notice, and has launched an important pilot project to assess WASH in Catholic-run health care facilities in low-resource areas. In undertaking this initiative, it opened up a looming question: What does the WASH situation in these facilities look like?

Two donkeys make 20 trips a day to transport water from a dirty stream where animals drink and people bathe to a health care facility in Ethiopia.

THE DEVASTATING SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Examples of the challenges health systems face without WASH abound, and Mike Paddock, former chief engineer for Engineers Without Borders-USA, has seen plenty of them.3 "I will never forget the day," Paddock once told me, "that I had to inform a hospital director that his wastewater system was the cause of the typhoid outbreak he was desperately fighting. You can't imagine the agony on his face."

Paddock's stories are hard to forget — he's traveled the world leading humanitarian, WASH and infrastructure projects in some of the world's most remote, challenging and impoverished environments. For example, Paddock was asked to inspect WASH at a Guatemalan regional government hospital that serves more than 250,000 people. He was initially pleased when he saw a functional waste management system hooked up to the municipal sewer system. But when the staff told him they had no idea where the sewer went, he feared he'd seen this situation before. He found the municipal wastewater dumping into a river nearby, and later that day, he found himself slamming on his brakes to intervene when he saw a water tanker filling up with that river water downstream from the hospital.

The most shocking WASH conditions are often found in labor and delivery areas where life takes its first breath. Millions of women must actually haul their own water to give birth in dirty and often overcrowded maternity wards. In some cultures, newborns are not named because early death is so commonplace. When I was traveling in Ethiopia, I heard stories from so many women who had lost a child during childbirth that (I'm ashamed to say) I caught myself reacting with surprise when a woman hadn't lost a child. Try to wrap your head around the fact that an unspeakable and rare tragedy here is daily life there.

Among the deadly causes are health care-associated infections (HAIs). Not surprising, newborn infections are three to 20 times higher in resource-limited settings where infections can be transmitted by unwashed hands, contaminated beds, unsafe water and dirty instruments used to cut umbilical cords.4 Nurses and midwives cannot adequately wash their hands to keep themselves and their patients safe (even during COVID-19), and women cannot adequately clean themselves after they give birth. Caring for post-partum hemorrhage and bleeding are impossible without water and sanitary pads. Toilets are routinely scarce, broken and filthy and the lack of waste management finds health care facilities littered with used menstrual products alongside all forms of contaminated medical and human waste. Moreover, poor WASH conditions stop pregnant women from seeking maternity services in facilities with trained staff, further undermining their health and the health of their child.5

Day One is when more than 40% of maternal and newborn deaths occur, although the majority of these deaths are preventable. More than 1 million deaths each year are associated with unclean births, while infections account for 26% of neonatal deaths and 11% of maternal mortality. Contrast that with handwashing and clean birthing practices: when in place, newborn survival rates increase up to 44%.6-9

WITH BETTER HYGIENE RESOURCES, MORE WOULD SURVIVE

To say that the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul have seen it all is almost an understatement. Since their founding in 1633, the order has provided health care in the streets, in villages and in hospitals, wherever the need was urgent and the resources scarce. Today, many sisters are highly trained physicians, nurses and ancillary professionals. But no medical professional can compensate for the lack of water and sanitation systems that plague facilities.

"If they had these basics, more babies would survive their first month, more children would grow to school age, more adults would be there to care for their families, and more health care providers would survive to serve in the next time of need," says Sr. Mary Louise Stubbs, DC, executive director, Daughters of Charity International Project Services. "Sisters around the world are true heroes who do not know they are being heroic; they only know that they are needed to bring health care to the sick, and they only know that water is a rare treasure without which their work is crippled."

This pink pail serves as a water source for a health clinic in Nepal. Water and sanitation improvements are beginning at health care facilities in dozens of countries, but greater prioritization and budgets are needed for sustainable progress.

THE BEGINNINGS OF A SOLUTION

Chiapas, Mexico, an impoverished region that has seen its share of unrest, is the site of the San Carlos Hospital, established in 1969 and run by the sisters since 1975. This busy rural hospital reaches 349 communities, averaging 17,000 consultations annually that cover outpatient visits and admissions, pediatrics, OB/GYN and internal medicine. It has a pharmacy, operating room, X-ray, ultrasound, a lab and it covers community health, too. Sr. Adela Orea, DC, the hospital's energetic administrator, recalls "a lot of anguish and a great burden" during her 37 years of experience. "When there is no hygiene, when there are no conditions to test for sepsis and asepsis in hospitals, this can become a focus of infection. And instead of providing health, we succumb to infections and disease."

The facility's early water situation required pumping water of poor quality from the nearby river. Water for drinking and sanitation was upgraded with access to a spring, but as the region's population grew, residents needed water, too, and tapped into the hospital's waterline for household needs. As a result, the demand on the spring grew far greater than the amount of water it could produce, and the spring's pump became costly to maintain. The sisters sought a solution. Collaborating with Water Engineers for the Americas and Africa, a professional volunteer organization, and with local government cooperation, they were able to get a new storage tank and pipes, which also accommodates community needs.10

Similarly, the Uganda Catholic Medical Bureau11 conducted WASH assessments of 14 health care facilities in the Tororo Archdiocese in 2017-2018 and subsequently procured 43 handwashing facilities, several water storage tanks and posted hand hygiene and safe waste segregation information for staff. (Well-timed given a global pandemic was to break out.) Some facility managers went further, renovating toilets and bathrooms, constructing incinerators, organizing refresher hygiene training and reconsidering facility design to accommodate people with disabilities. The Uganda Catholic Medical Bureau disseminated assessment findings to bishops to raise awareness and support for subsequent WASH in health care facility projects in Uganda.

The organization also worked with Engineers Without Borders to bring water to the Dabani Hospital in the Tororo Diocese. This facility offers care to nearly 26,000 people across 52 villages. Rather than paying someone to fetch water, water is now piped into all wards, which increases handwashing and infection prevention control. Infection rates are anticipated to drop. The hospital project also extended water access to the community and neighboring primary school. Dedicated cost-sharing will help ensure operations and maintenance.

And here's the thing: These relatively uncomplex examples illustrate that the problem of a lack of WASH in health care facilities is solvable. But it is a systems issue and must be addressed as such.

A maternity room in Ethiopia lacks access to clean water, needed for patient safety and dignity.

THE VATICAN RESPONSE

Answering a moral call, the Vatican launched a landmark initiative in 2020 to improve WASH in the health care facilities it runs, led by the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, under its prefect, Cardinal Peter K.A. Turkson.12 The Vatican focus on this global issue provides important leadership and influence, and will lead to safer care for millions of people.

The dicastery first drew attention to the lack of WASH in health care settings in its 2018 World Water Day communique, "Aqua Fons Vitae."13 Then, in his letter of August 2020 to Catholic Bishops' Conferences worldwide, Cardinal Turkson called for WASH, "in order to safely treat patients, prevent further spread of COVID-19 and other diseases, and protect health care workers and chaplains who are doing God's work by caring for the sick." His letter invited each bishop to voluntarily take part in an effort to ensure proper WASH standards with infrastructure, equipment, maintenance and staff training at all health care facilities within their dioceses.

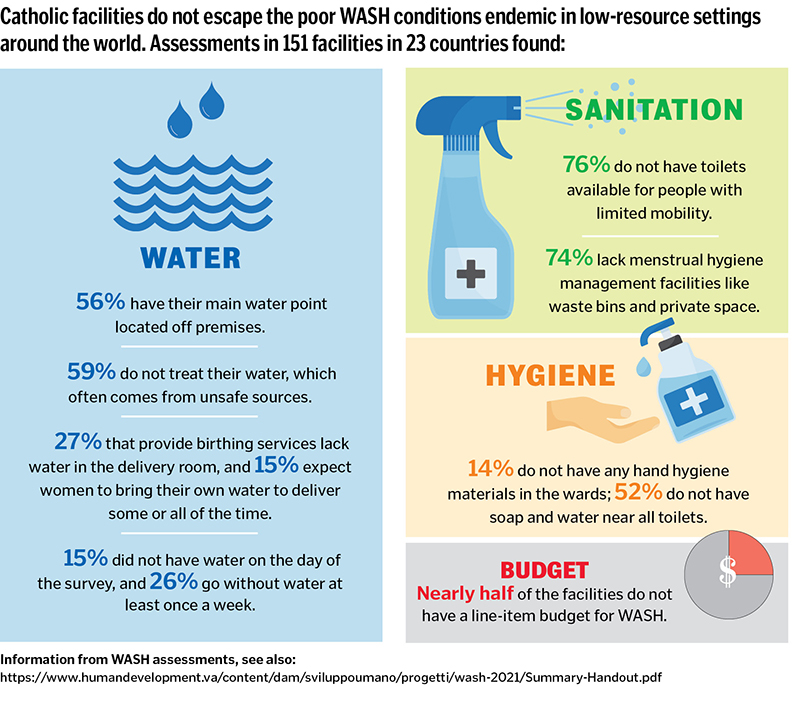

The reaction was massive, reflecting the need. Bishops in 23 countries responded. The dicastery subsequently completed WASH assessments in 151 pilot facilities across the 23 countries. These facilities serve areas encompassing some 28 million people. Assessments were carried out by the hospitals and clinics, trained by Catholic Relief Services, Caritas Internationalis and Global Water 2020, in coordination with the Dicastery.14-16

Each facility received a report that identified its strengths and gaps, and was encouraged to start incremental improvements that require no or minimal funding. Private and public sector partners and donors are being sought to mitigate the larger WASH needs. Once funding for a specific health care facility or facilities is identified, full technical studies will be completed and available to the donor with multiple routes for donor engagement.

Importantly, each health care facility and implementing organization is committed to ensuring that sustainability is built-in from the start, with 5% of costs dedicated to ongoing maintenance and repair. Inevitably, pipes, wells, water tanks, sinks, toilets and more break, especially when they've not been maintained for years, if not decades, due to the lack of funds, training, supplies and neglect. While the Dicastery itself will limit its role to seeking funding for the initial 151 pilot health care facilities, this effort is the starting line, not the finish line, for Catholic facilities.

Sr. Gina Marie Blunck, SND, is executive director of the Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters, established in 1986 to support the ministries of Roman Catholic sisters. Access to safe drinking water is one of the fund's health priorities, and each year at least 10% of its projects provide water to a facility and surrounding community. Sr. Blunck not only commends the Dicastery's efforts to identify WASH-needy facilities globally, she says the fund "will select facilities owned and operated by a congregation of sisters and provide funding in collaboration with others. The Fund for Sisters is anxious to participate in this collaborative, which will benefit the sisters and address the health, sanitation and hygiene of those they serve."

GLOBAL MOMENTUM IS GROWING

The Vatican initiative is well-aligned with Catholic teaching and global need. "Catholics work hard for human rights," Sr. Orea reminds us from her facility in Chiapas. "The right to health is one of the most inalienable rights of the human being. Whoever has water, has life."

Though the Vatican's engagement is particularly significant due to the Church's vast global reach, neither the Vatican nor the sisters are alone among faith-inspired efforts to get WASH in health care facilities. Noteworthy work is also being undertaken by organizations such as World Vision, Nazarene Compassionate Ministries and the Aga Khan Development Network, among others.

United Nations entities are also increasingly prioritizing this issue with country-led engagement, roadmaps and standards.17 In addition, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is working to increase its partnerships with a diverse faith community. Rev. Adam Phillips leads USAID's Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships and USAID's Local, Faith and Transformative Partnerships Hub. Phillips appreciates that faith-based organizations have "long-standing connections with hospitals, clinics, local leadership and communities [that] have made them the go-to resource for information, basic needs and emotional and spiritual support." He describes the need for diverse stakeholders to improve WASH in health care "to ensure quality of care, dignified environments and improved well-being for everyone who walks through the doors." Those stakeholders need to include leadership by ministries of health and other ministries, and service providers that include faith-based organizations, as well as local governments, the private sector and communities.

CHA also assists by raising the profile and discussion of WASH among its network of U.S. health providers that offer international support. It has a history of supporting efforts in Haiti post-earthquake, and will do so again by supporting the inclusion and maintenance of much-needed WASH in 10 health care facilities that each serve multiple communities throughout all 10 departments in Haiti.

With growing momentum, faith-based, secular and government institutions that provide health care are finally beginning to see that tackling this solvable problem is a foundational route to the hope, dignity and healing that health care is meant to provide. Health care for all can be what I experienced.

As I started to stir after my surgery, a kind nurse came over with a welcome offer: a cup of cool clean water, which I accepted with perhaps extra gratefulness that came from these scenes I replayed in my mind.

FOR MORE INFORMATIONVatican WASH in Health Care Facilities Initiative: water@humandevelopment.va Sr. Mary Louise Stubbs, DC, Executive Director, Daughters of Charity International Project Services: marylouise.stubbs@doc.org World Health Organization WASH in health care facilities resources: www.washinhcf.org Bruce Compton, Senior Director, Global Health, Catholic Health Association of the United States: bcompton@chausa.org |

SUSAN K. BARNETT is founder of Faiths for Safe Water and part of the Global Water 2020 initiative, which focused on underrepresented issues of global water health and security. She was a journalist with the network newsmagazines PrimeTime Live, 20/20 (ABC News) and Dateline NBC. She now leads Cause Communications. For more, see www.faithsforsafewater.org/.

NOTES

- "Global Progress Report on WASH in Health Care Facilities: Fundamentals First," World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017542.

- "Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Health Care Worldwide," National Center for Biotechnology Information, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535654/.

- Engineers Without Borders, https://www.ewb-usa.org/.

- Anita K. M. Zaidi et al., "Hospital-Acquired Neonatal Infections in Developing Countries," The Lancet 365, no. 9465 (26 March–1 April 2005): 1175-1188, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71881-X.

- Maha Bouzid, Oliver Cumming and Paul R. Hunter, "What is the Impact of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Healthcare Facilities on Care Seeking Behaviour and Patient Satisfaction? A Systematic Review of the Evidence from Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries," BMJ Global Health 3, no. 3 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000648.

- Dr. Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, "Integrated Strategies to Address Maternal and Child Health and Survival in Low-Income Settings: Implications for Haiti," Permanente Journal 20, no. 2 (Spring 2016): 94-95, https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-204.

- "Water, Sanitation and Hygiene," United Nations, https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/water-sanitation-and-hygiene/.

- "Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Health Care Facilities: Practical Steps to Achieve Universal Access to Quality Care," World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311618/9789241515511-eng.pdf.

- Victor Rhee et al., "Maternal and Birth Attendant Hand Washing and Neonatal Mortality in Southern Nepal," Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 162, no. 7 (2008): 603–608, https://jhu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/maternal-and-birth-attendant-hand-washing-and-neonatal-mortality--4.

- Water Engineers for the Americas and Africa, https://www.wefta.net/.

- Uganda Catholic Medical Bureau, https://www.ucmb.co.ug/.

- "WASH Conditions in Catholic Health Facilities," Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, https://www.humandevelopment.va/en/news/2021/wash-conditions-in-catholic-health-facilities.html.

- "Aqua Fons Vitae," Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, https://www.humandevelopment.va/en/risorse/documenti/aqua-fons-vitae-the-new-document-of-the-dicastery-now-available.html.

- Catholic Relief Services, https://www.crs.org/.

- Caritas Internationalis, https://www.caritas.org/.

- Global Water 2020, http://globalwater2020.org/index.html.

- "Fundamentals First.".