Mark Repenshek, Ph.D.

Healthcare Ethicist

Columbia St. Mary's Hospital

Milwaukee, WI

In the Winter 2008 issue of Health Care Ethics USA, I contributed an essay analyzing 196 clinical ethics consultations from 2003 to 2007 in an attempt to open a dialogue regarding standards for the ethics consultation process.1 In conjunction with that essay, the Catholic Health Association established a Beta group, consisting of several ethicists from across the country, who agreed to utilize the software that I was employing in order to capture, measure, and evaluate ethics consultations at their respective ministries. The intention was to develop a broader consensus on standards for the practice of ethics consultation along with measures for quality and effectiveness, and to spur dialogue on what criteria should constitute qualifications for practitioners within Catholic health care. Given the significant dialogue on these topics outside of Catholic health care,2 it seemed most appropriate to begin to address these issues in the context of our own ministry. This piece will reflect on the creation of the Beta group, its place in the ongoing dialogue on quality and effectiveness in clinical ethics consultation in relationship to the Clinical Ethics Credentialing Project, and end with a plea for collaborative next steps with health care institutions inside and outside the Catholic health care ministry.

Current Discourse Outside the Ministry: Where is Catholic Health Care?

In the October 2009 issue of the Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, all articles focused on a central theme: "[A]lthough still in a formative and dynamic phase of development, clinical ethics is now sufficiently mature to be open to critical self-examination, including empirical investigation."3 Agich and Reiter-Theil's call should not fall on deaf ears in Catholic health care, given our ministry's directed attention to ethics consultation:

An ethics committee or some alternate form of ethical consultation should be available to assist by advising on particular ethical situations, by offering educational opportunities and by review and recommending policies. To these ends, there should be appropriate standards for medical ethical consultation within a particular diocese that will respect the diocesan bishop's pastoral responsibilities as well as assist members of ethics committees to be familiar with Catholic medical ethics and, in particular, these Directives [emphasis added].4

It is clear from Directive # 37 of the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Healthcare Services (ERDs)that the Catholic health care ministry should already be able to demonstrate the integrated role of ethics consultation into particular consultative contexts, educational opportunities and policy development. Additionally, it is also clear that Directive #37 requires that appropriate standards for such consultation should be informed by a robust understanding on the part of committee members of the principles of medical ethics found in the Catholic moral tradition as well as the principles derived from that normative tradition and given greater specificity in the ERDs. Were it the case that the Catholic health care ministry has achieved these standards in its ethics consultation services across the ministry, there would be much we could offer our non-Catholic partners in these regards. It does not seem, however, that Catholic health care has embodied these standards. Moreover, we seem to be lagging behind the constructive dialogue occurring outside Catholic health care on the matter of "standards for medical ethical consultation" despite the prescriptive language found in Directive # 37.5

Returning to the October 2009 issue of the Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, George Agich opens the issue by suggesting that despite the increasing accountability to quality in every other area of health care, clinical ethics consultation has heretofore been somehow exempt. He suggests that the field must foster a "robust internal commitment to quality" alongside an external accountability in order to be a responsible practice. Agich's focus on clinical ethics consultation as a responsible practice forms the basis for his approach and for the expectations of full accountability derived from it. According to Agich, the development standards that constitute responsible practice should not be, and need not be, hampered by a general lack of consensus on the right model for ethics consultation (e.g., individual, subcommittee or ad hoc group). In fact, a quality assessment can and should occur whatever an institution's particular model of clinical ethics consultation.

Robert D. Orr and Wayne Shelton, in the Spring 2009 issue of The Journal of Clinical Ethics, propose a process and format for clinical ethics consultation developed over their 20-year history of providing bedside ethics consultation and teaching graduate students on how to do clinical ethics consultation.6 Their approach appeals to a standardization of components of a clinical ethics consultation process wherein, regardless of consultant model (i.e., individual, subcommittee or ad hoc group), the methodology assures that relevant data are gathered and analyzed before any recommendation is made. Additionally, Orr and Shelton argue for a standard in documentation of the clinical ethics consultation that demonstrates that a "systematic and thorough investigation has been made into the question or problem that has been presented to the consultant" with an eye toward utility for the clinical team.7

An article by Douglas J. Opel et al.,in the Fall 2009 issue of The Journal of Clinical Ethics moves beyond the question of whether ethics consultation ought to be subject to quality assessments to the matter of recommending a quality improvement tool.8 Of note is these authors' unequivocal position that ethics consultation must be assessed from a quality standpoint. Further, the real debate lies in how. They propose using a tool familiar to risk management, namely, root cause analysis. For these authors, the ultimate goal of any ethics consultation process should be to "look upstream," to identify and improve the systems problem that resulted in an ethics consultation. In this way, they argue, root cause analyses and similar processes "result in a general improvement in the quality of care delivered."9

Finally, in the November-December 2009 issue of the Hastings Center Report, the Clinical Ethics Credentialing Project takes a comprehensive approach to three areas where the project found little consensus: (1) standards for practice (outside of the Veterans Administration system), (2) qualifications for practitioners, and (3) valid and reliable measures to rate the quality and effectiveness of the clinical ethics consultation process.10 This bold project made three important contributions to this discussion: (a) Fundamental Elements of Clinical Ethics Consultation; (b) Standards for Clinical Ethics Consultation; and (c) an eight-step process for assessing the quality of the ethics consultation process.

Although there are pockets of good work in these areas occurring within Catholic health care, there is no identified body within the ministry that has taken responsibility for attending to Directive #37. The Catholic health ministry seems best suited to address these issues in clinical ethics consultation for a number of reasons: (a) there is a uniform set of guidelines and principles by which Catholic health care understands ethical decision-making;11 (b) there is a uniform expectation for what should minimally constitute an ethics consultation service within Catholic health care (Directive # 37); and (c) with a long-standing tradition of theological reflection on life, death, suffering and the intersection of these with medicine and the good of health, theologians have been able to enter early debates in bioethics effectively so as to create a wealth of literature relevant to clinical ethics consultation in a Catholic health care ministry.12 Yet, we have no established standards for what constitutes clinical ethics consultation in Catholic health care, no standards for qualifications of persons responsible for clinical ethics consultation, and no valid or reliable measures to rate the quality and effectiveness of clinical ethics consultation in the Catholic health care ministry. Sadly, despite our early and forceful positioning in the bioethics field,13 we have remained relatively absent from these more recent discussions in the bioethics literature.14

An Attempt to Re-engage: The Catholic Health Association Ethics Tracker Beta Group

In 2006, Columbia St. Mary's (CSM) ethics consultation service began using a Microsoft Access database developed by Harmony Technologies15 to capture critical elements of ethics consultation. I published on this data from 2003 through 2007 in a past issue of Health Care Ethics USA and will not expand on that here.16 Of importance for this essay, these data were based on ethics consults where: (a) the initial ethics committee member could identify an ethical dilemma; (b) the consultant(s) could identify the person requesting the consultation; and (c) offer recommendations where appropriate to the reason for the request. Data were abstracted from completed ethics consultation intake forms, written analyses and recommendations, and patient medical records. Additionally, the model for ethics consultation used at CSM was and continues to be based on the American Society for Bioethics and the Humanities' Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation.17 In light of these competencies, CSM's specific ethics consultation service model would best be characterized as an ethics facilitation approach18 framed by the mission, vision and values of the health care ministry. This background is important because it represents presumptions around an ethics consultation model that undergirds the data that populate the database. Because the Ethics Tracker database was simply exported to participants of the CHA Beta group, the validity of these presumptions was not tested. Nonetheless, the CHA Beta group does offer a response to points (1) and (3) of the Clinical Ethics Credentialing Project's critiques of the current state of affairs in clinical ethics consultation.19

Standard for Practice

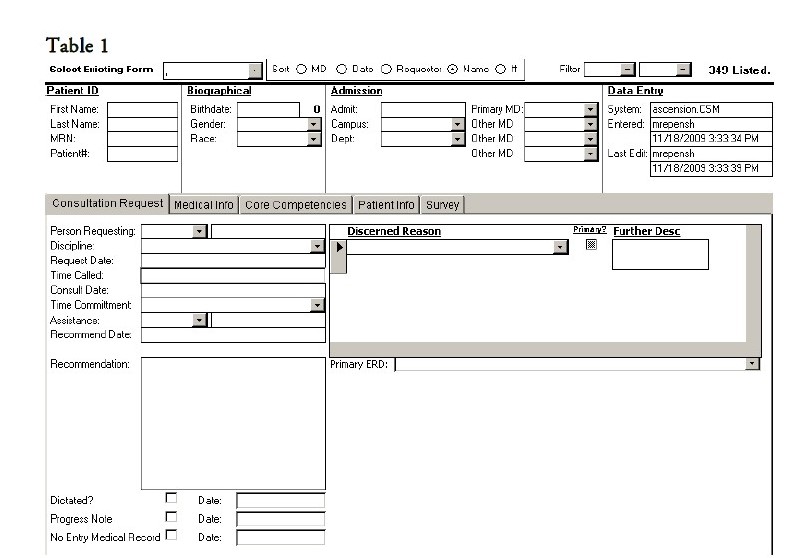

Given the data fields that offer input into Ethics Tracker, an implicit claim is made as to the fundamental elements of clinical ethics consultation (see Table 1). Interestingly, although the CHA Beta group was not involved in the Clinical Ethics Credentialing Project, the data fields align well with the recommendations of the Project's Fundamental Elements of Clinical Ethics Consultation. This suggests that although there is an often-cited claim that "variations of practice are considerable," the variations may not be as considerable as previously thought.20

All data elements required in Table 1 illustrate that: (a) the ethics consultation is tracked for its timeliness between request for and completion of an ethics consultation; (b) a review of the patient medical record must occur; (c) a primary reason for consultation must be discerned with potential for secondary and tertiary reasons noted; (d) one must assess the level of consultation that will best aid in determining whether and to what extent a further process with hospital leadership or bioethics committee is necessary; and (e) one needs to note whether and to what extent the ethics consultation was documented in the medical record.

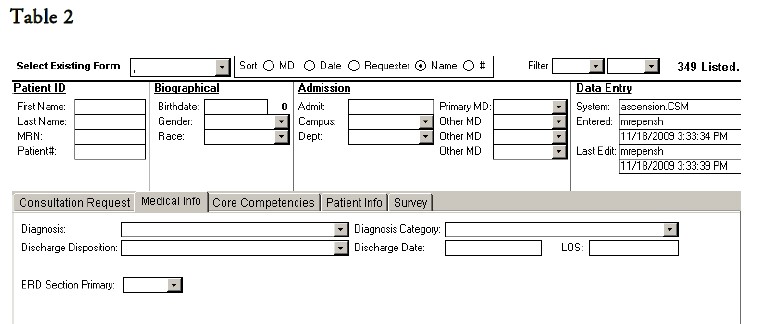

Finally data elements in Table 2 illustrate attention to: (a) clinical diagnoses and (b) discharge disposition in order to establish a basis for continued review and trends related to the major diagnostic category to which the patient's primary diagnosis is attributed as well as the discharge outcome following ethics consultation.

Valid and Reliable Measures to Rate the Quality and Effectiveness of the Clinical Education Consultation Process

Opel et al. rightly point out that "much of the attention on quality in ethics has focused on improving the internal structures and processes within ethics consultation services … [but] we challenge ethics consultants to look beyond the traditional confines of clinical ethics."21 In this way, the authors argue that quality improvement efforts in ethics consultation must include both the "quality of practice within ethics consult services, [and] … the quality of health care provided throughout the system."22 Ethics Tracker attends to these goals through its use of documentation standards for ethics consultation.23

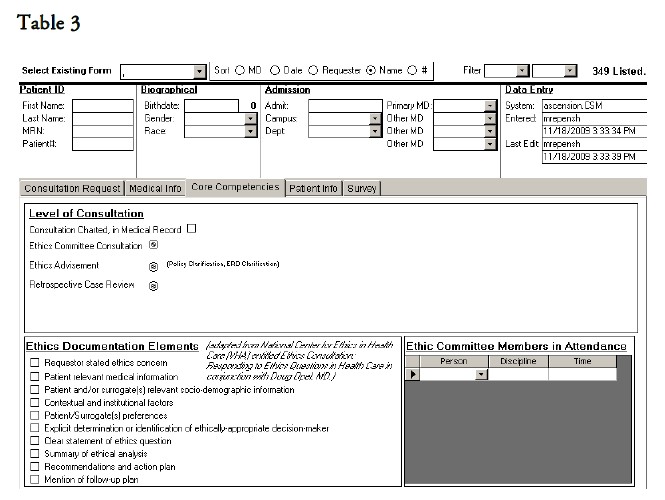

In relationship to standards developed by the Clinical Ethics Credentialing Project, the data elements in Table 3 illustrate attention to: (a) the interdisciplinary nature of the ethics committee in relationship to the expertise relevant to the reason for ethics consultation; (b) the nature of the consultation requested in relationship to policy definitions surrounding what constitutes advisement versus consultation; and (c) standard documentation elements of the ethics consultation in the medical record for later quality improvement.

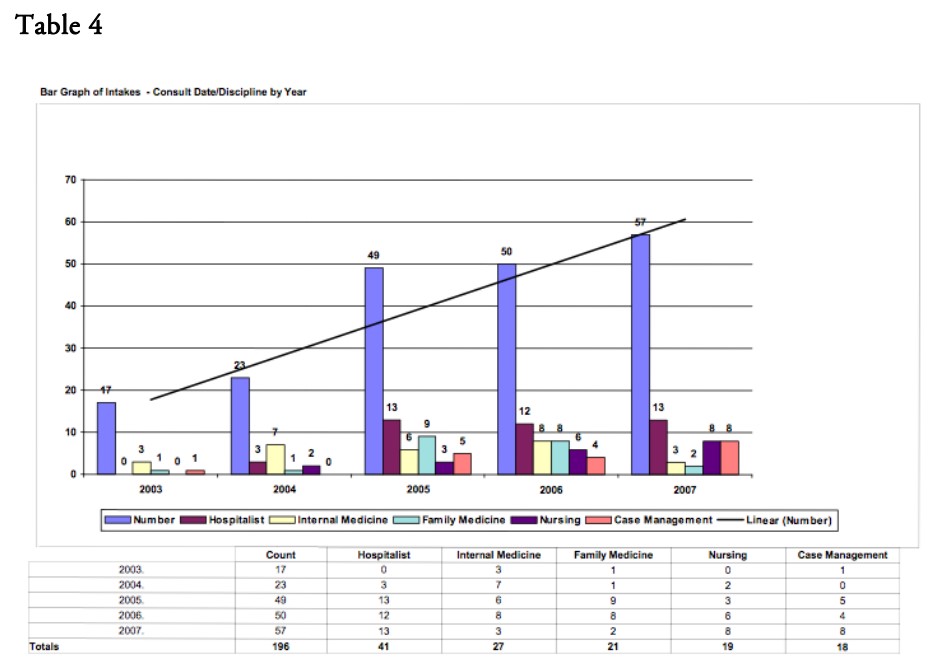

Not captured in these Tables is an evaluation tool for requester satisfaction based on timeliness and requester satisfaction. Table 4 illustrates this tool.

Ethics Tracker automatically issues an email to the requestor of the ethics consultation and secures (locks) the email response to these evaluation questions for integrity of the data.

Collaborative Next Steps

As mentioned earlier, the Beta group did not examine the assumptions about what constitutes an ethics consultation, but rather simply accepted them as part of the goal of standardization in the use of the Ethics Tracker database. Yet, it is these very assumptions that remain untested in the broader ethics literature on clinical ethics consultation.24 Returning to the Clinical Ethics Credentialing Project, one sees that standards for clinical ethics consultation have been established. Those standards include: (1) easy access to clinical ethics consultation (CEC) and a plan for responding to requests for CEC from staff, patients, and family members (or other patient representatives); (2) a clear process for gathering information and making appropriate arrangements to make sure all relevant stakeholders are heard; (3) a formal note in the medical record; (4) a standard format for writing in the chart; (5) recognition of CEC as one of many collaborating services that must be integrated and transparent in its functioning; (6) institutional and peer oversight; (7) methods of ensuring the qualifications and competency of CE consultants; (8) measures for credentialing CE consultants; and (9) a robust quality improvement process.

It is time for the Catholic health ministry to engage the literature concerning the model for ethics consultation along with the standards of what constitutes an ethics consultation. To date, much of the literature contributed from Catholic health care ministries has focused on a model or a set of standards25 Often cited definitions of what constitutes a clinical ethics consultation serve as illustrative points of departure between the Catholic health care ministry and non-Catholic entities offering an ethics consultation service. For Catholic health care, an essential way to understand the purpose of an ethics consultation service (in existence with other "centers of ethical responsibility") is as "the systematic effort to discern the imperatives of human dignity."26 For non-Catholic entities, on the other hand, the purpose of an ethics consultation service "is to improve the process and outcomes of patient care by helping to identify, analyze, and resolve ethical problems."27 This is not to say that there cannot be convergence between these two visions of what constitutes clinical ethics consultation, but where Catholic health care is explicitly called to establish "appropriate standards for medical ethical consultation" consistent with its understanding of the purpose of an ethics consultation, an obligation exists to discern standards for those who enter the privileged space of the patient physician-relationship to offer ethics consultation.

NOTES

- Other analyses on clinical ethics consultation offer similar or considerably lower numbers of consults and none are within a Catholic healthcare ministry. See, K.M. Swetz, et al., "Report of 255 Clinical Ethics Consultations and Review of the Literature," Mayo Clinic Proceedings 82 (2007): 686-691; R. Forde and I. H. Vandvik, "Clinical Ethics, Information, and Communication: Review of 31 Cases from a Clinical Ethics Committee." Journal of Medical Ethics 31 (2005): 73-77; D. B. Waisel, et al., "Activities of an Ethics Consultation Service in a Tertiary Military Medical Center," Military Medicine 165 (2000): 528-532; T. Schenkenbert, "Salt Lake City VA Medical Center's First 150 Ethics Committee Case Consultations: What We Have Learned (so far)," HEC Forum 9 (1997): 147-158.

- Nancy Neveloff Dubler, et al., "Charting the Future: Credentialing, Privileging, Quality, and Evaluation in Clinical Ethics Consultation," Hastings Center Report 39, no. 6 (2009): 23-33.

- George J. Agich and Stella Reiter-Theil, "Guest Editorial: Encouraging the Dialogue," Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 18, no. 4 (October 2009): 333.

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services. (Washington, DC: 2001), Directive 37.

- For example, the dialogue occurring in the ASBH Affinity Group: Clinical Ethics Consultation Advisory Group (CECAG).

- Robert D. Orr and Wayne Shelton, "A Process and Format for Clinical Ethics Consultation," The Journal of Clinical Ethics 20, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 79-89.

- Orr and Shelton, p. 83.

- Douglas Opel, Dena Brownstein, Douglas Diekema, Benjamin Wilfond, and Robert Pearlman, "Integrating Ethics and Patient Safety: The Role of Clinical Ethics Consultants in Quality Improvement," The Journal of Clinical Ethics 20, no. 3 (Fall 2009): 220-226.

- Opel, et al.,p. 223.

- Nancy Neveloff Dubler, et al.,pp .23-33.

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, 4th ed. (Washington DC, 2001).

- Thomas A. Shannon, "Bioethics and Religion: A Value-Added Discussion," in Notes from a Narrow Ridge: Religion and Bioethics, ed., Dena S. Davis and Laurie Zoloth (Hagerstown, MD: University Publishing Groups, 1999), p. 31; David F. Kelly, The Emergence of Roman Catholic Medical Ethics in North America (New York: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1979); Gerald Kelly, Medico-Moral Problems (St. Louis, MO: The Catholic Hospital Association, 1958); Lisa Sowle Cahill, Theological Bioethics (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2005), p. 15.

- Albert Jonsen, The Birth of Bioethics (Oxford University Press, 2003).

- It should be noted that there is a significant amount of literature discussing the Next Generation model of ethics consultation in Catholic healthcare, but this model does not directly answer the critiques of the Clinical Ethics Credentialing Project nor the question of standards for the Catholic healthcare ministry such as those developed by ASBH. See, Kevin Murphy, "A 'Next Generation' Ethics Committee," Health Progress 87, no 2 (March-April 2006): 26; Gerard Heeley, "A System's Transition to Next Generation Model of Ethics," Health Care Ethics USA 15, no. 4 (Fall 2007): 2-4; Philip Boyle, "The Next Generation of Ethics Mechanisms: Developing Ethics Mechanisms that Add Demonstrable Value," Health Care Ethics USA 16, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 5-7; Gerard Heeley, "Next Generation Model of Ethics: One Ministry's Experience," Health Care Ethics USA 16, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 8-10.

- The author has no conflict of interest in Harmony Technologies, LLC.

- Mark Repenshek, "An Empirically Driven Ethics Consultation Service," Health Care Ethics USA 17, no. 1 (Winter 2009): 6-17.

- American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation: The Report of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (Glenview, IL: American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, 1998): 6-7.

- The ethics facilitation approach is defined in the ASBH Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation, 1998.

- Dubler et al., p. 23.

- E. Fox, S. Myers and R.A. Pearlman, "Ethics Consultation in United States Hospitals: A National Survey," American Journal of Bioethics 7, no. 2 (2007): 13-25.

- Opel, et al.,p. 221.

- Opel, et al.

- These standards were developed in conjunction with Douglas J. Opel at the Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics and the Veterans Affairs National Center for Ethics in Health Care IntegratedEthics Program and through the use of the Reports Function in Ethics Tracker concerning a number of quality tracking fields already highlighted in the Winter 2009 issue of Health Care Ethics USA. See, Repenshek, "An Empirically-Driven Ethics Consultation Service," pp. 10-16.

- Dubler et al.,"Charting the Future," p. 23; E. Fox, S. Myers, and R.A. Pearlman, "Ethics Consultation in the United States Hospitals: A National Survey," pp. 13-25; M. Dowdy, C. Robertson, and J.A. Bander, "A Study of Proactive and Ethics Consultation for Critically and Terminally Ill Patients with Extended Lengths of Stay," Critical Care Medicine 26 (1998): 252-9.

- Philip Boyle, "The Next Generation of Ethics Mechanisms: Developing Ethics Mechanisms that Add Demonstrable Value," Health Care Ethics USA 16, no. 1 (Winter 2008):

- John W. Glaser, "Hospital Ethics Committees: One of Many Centers of Responsibility," Theoretical Medicine 10 (1989): 275-288.

- American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation: The Report of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, p.3.

Copyright © 2010 CHA. Permission granted to CHA-member organizations and Saint Louis University to copy and distribute for educational purposes. For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.