By JULIE MINDA

There is a massive amount of data that providers generate in the delivery of health care, and much of that data is highly sensitive, personal information. A lot of the data is so valuable that third-party companies are willing to pay handsomely to access it.

Miller

MillerGiven these and other dynamics of the digital data environment, it is important, in the view of Michael Miller, SSM Health system vice president of mission and ethics, that all health care organizations be extremely careful about how they handle data.

In a webinar titled "Data and Ethics in Health Care," Miller said it is essential for Catholic health care organizations in particular to thoroughly vet and monitor all plans and implementations for data use from an ethical perspective.

Describing the value of health care data, Miller called it the "new oil" of today's digital environment — just as petroleum reserves promised untold wealth in the 1800s in the U.S., the troves of health care data that are being generated are hugely valuable today.

Health care systems and facilities must guard this precious commodity carefully, Miller said, including by understanding how data is collected, used and maintained at their organizations.

Miller's webinar on May 3 was an installment of "Emerging Topics in Catholic Health Care Ethics." That webinar series is sponsored by CHA, Georgetown University, Loyola University Chicago and Saint Louis University.

Common good for data use

Miller explained that ethical concerns around data use fall under the category of applied ethics. Some of the ethical principles that come into play have to do with respect for human dignity and considerations around the common good, as captured in the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services.

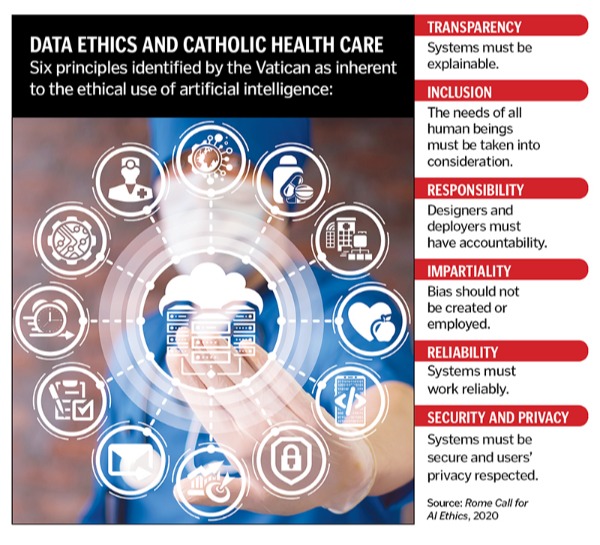

Miller noted that numerous organizations have been deliberating and delineating ethical concepts for data use in health care. The Vatican, for instance, issued in February 2020 a Rome Call for AI Ethics. That document puts forth high-level categories for evaluating the use of data, including reliability, transparency, inclusion, impartiality, security and privacy, and responsibility. Miller said the framework from the Vatican can be very useful for ministry organizations and others as they are making decisions around data use.

Miller explained that there are many types of health care data, including structured data, which is specific, quantitative data points; unstructured data, which are clinical notes and other qualitative information; administrative data, which has to do with backend processes like coding and billing; patient-generated data such as that coming from Fitbits and other biometric trackers; population health data; and consumer data.

Revenue stream

During the webinar, Miller elaborated on top areas of concern when it comes to health care data.

He described the great potential to monetize such data and the possible hazards of doing so. Data is a prized commodity because it can help organizations unlock clues to patient and consumer behavior. It can be very lucrative for the organizations that possess such data to sell it. Creating a revenue stream in this way can be of much interest to providers, and especially ones that are operating on tight margins. But, challenged Miller, under what parameters is it OK to fuel economic progress by extracting and selling data from patients? How does such activity either promote or hinder human flourishing?

Miller also described the "myth of big data," or the potentially false belief that the more data organizations have, the more problems they can solve with the data. Miller asked rhetorically what the purpose is of storing up data and whether data will be used in a way that is an appropriate reflection of who ministry providers are.

Relatedly, he warned of the potential to perpetuate bias through the wrong use of health care data. To illustrate, he laid out a case study in which algorithms a group of data scientists used to process health care usage data for a study were based on false assumptions. As a result, he said vulnerable people were denied appropriate, timely care when the study results were applied to a care access policy.

Privacy and security

Miller noted that while most health care providers are well attuned to the need to protect health care data from exposure, there can be a false security when providers give third parties access to deidentified data. That is data that has had patient identification information removed. Miller said that there is much value to companies in connecting disparate data sets in order to draw linkages among the data points included in those sets. Reconnecting data in different sets introduces the potential for third parties to inappropriately "reidentify" patients, Miller cautioned.

In a related topic, Miller said that privacy and security are always in counterbalance to each other. To illustrate this concept, he described how video doorbells can help provide a layer of security for a resident, but potentially can violate the privacy of people passively walking by. When those people are recorded, there is the possibility their privacy could be violated.

Power dynamics

Miller also brought up concerns around informed consent of patients when it comes to the use of their data. There is a history of various types of abuse of the provider-patient relationship and so it is an essentiality in health care that patients are informed about all aspects of their care and that they are told the implications of that care. He related the concept to questions around power dynamics when it comes to individual patients on one hand and large, powerful companies on the other.

He asked to what extent patients can consent to the use of their data, whether they can understand the full implications of the use of their information and whether they really have the power to opt out of their data being used. Miller likened it to the experience of having to accept all the terms of service in a lengthy user agreement when buying a smartphone. Usually, a phone buyer cannot use the phone without agreeing to all the conditions put forth by the phone company.

Green concerns

Miller also flagged the dangers of falling prey to "AI hype," or the sensationalism around artificial intelligence. He said technology cannot and should not be seen as the end-all solution for problems and by the same token it should not be viewed as an untamable tool.

He also elaborated on concerns around the environmental impact of big data. The generation, processing and storage of data requires the erection of gigantic data centers around the world filled with rooms of servers. Those data servers use copious amounts of energy to run. To what extent do health care providers consider the environmental cost of operating these data centers? Miller wondered.

To close out the webinar, Miller said he's aware that there is great work already being done by ministry systems and facilities to pay heed to such concerns. He advised that providers continue to work together to stay on top of the considerations.

"We need to ask the questions of 'why.' When looking to collect data, we need to ask why and to explore the implications," he said. "We need to create oversight groups to make sure we're deploying technology in alignment with our Catholic identity. We need to explore the implications of developing technologies."

Miller referenced an article he co-authored with others from within the Catholic ministry, "Data Ethics in Catholic Health Systems." That article is available for purchase at tinyurl.com/5xdmar46.