End-of-life care for a child creates a "special sort of heartbreak and brokenness" for parents and care providers and poses ethical issues that are not present as death nears for most adults, says Erica K. Salter.

An associate professor of health care ethics and pediatrics at the Albert Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics at Saint Louis University, Salter discussed those ethical issues and her thoughts on them during a webinar Dec. 9 sponsored by CHA in partnership with Georgetown University, Loyola University Chicago and Saint Louis University.

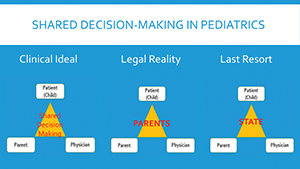

One of the unique circumstances in pediatric cases is that young patients are presumed to not have the capacity to make their own decisions, Salter says. Another is that parents generally are presumed to be the best surrogate for those decisions.

Parents' authority to make care decisions for their children, which has been backed up by court decisions, is based on several factors, including their knowledge of their child's best interests, the fact that they bear responsibility for the child in all other aspects of life and the presumption that they are in the best position to make good decisions for their whole family, she notes.

Salter calls parents' responsibility for their child "deeply ontological" in that the reality within which the child exists is largely dictated by his or her parents and the choices the parents make.

"I would argue that, altogether, these reasons do justify parental authority in health care decisions and their implications," she says. "It's really difficult to extract these decisions from this wider context and to do so would be to sort of isolate them in an artificial way."

Even given this preeminent role for parents when a child is dying, Salter says clinicians' guidance is nevertheless important to help families articulate goals of care. Unlike for adults, she notes, families of young patients generally haven't thought about end-of-life wishes.

To determine the best course of action for the family, Salter suggests that clinicians pose questions to parents such as: What are you hoping for? What is most important to you? What are you most afraid of? Clinicians should document the answers and make recommendations on care decisions with the parents' preferences in mind, she says.

Salter adds that care providers have a duty be mindful of refusals of care by parents that could put their child at risk of harm. To decide whether the risk is significant enough to call for outside intervention, she suggests that clinicians follow the criteria outlined by Dr. Douglas Diekema, a pediatric bioethicist, in "Parental refusals of medical treatment: the harm principle as threshold for state intervention," an article published in the July 2004 edition of Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics. The conditions Diekema suggests should be met to consider intervention are covered in eight questions that include:

- By refusing to consent are the parents placing their child at significant risk of serious harm?

- Is the harm imminent, requiring immediate action to prevent it?

- Is the intervention that has been refused necessary to prevent the serious harm?

Where possible, Salter says, parents and clinicians should involve the child in care decisions. That can be as simple as letting them choose which arm an IV goes into or what time of day blood is drawn for labs or as delicate as talking with a child about a dire prognosis.

She references the work of Myra Bluebond-Langner, a researcher who found that, despite attempts from parents and providers to protect pediatric patients from the knowledge that their illness is terminal, children as young as 3 know when they are dying and can feel alone and abandoned if what they are experiencing is ignored.

"Probably the most caring thing or kind thing or compassionate thing we can do is to enter into that space with the child, acknowledge that this is terrible news but we're here, we're ready to listen and we are companions with them in this difficult process," Salter says.

Salter falls back on a mantra for what families should say to children in the most tragic of circumstances. It comes from Jenny Harrington Lill, who created a blog to document her family's struggle as her 8-year-old son was losing his battle with leukemia.

The mantra is: "You will not be alone. You will not feel pain. We will be OK."

A recording of Salter's webinar is available for CHA members at chausa.org/online-learning.