By BETSY TAYLOR

At the end of January, the World Health Organization said the fight against Ebola in West Africa had shifted from slowing transmission to ending the epidemic. At the time, more than 8,800 people had died in West Africa from the highly contagious illness, with the incidence of cases falling in Liberia and Sierra Leone, but a slight increase in Guinea.

Hospitals that rapidly geared up their Ebola preparedness efforts in the fall after the first Ebola death in the United States continued their vigilance in 2015.

Chesterfield, Mo.-based Mercy recently described its work behind the scenes to coordinate a system-wide response to prepare its hospitals, doctors' offices and clinics for any potential Ebola patients shortly after the first case of Ebola was diagnosed in the United States in Texas in late September.

Its Ebola preparedness team, which had been meeting on conference calls twice a day as prevention efforts ramped up in the fall, continued to meet once a week as Catholic Health World went to press in February. The team keeps current on the disease's progression in Africa and is doing additional planning on Mercy's overall disaster preparedness.

Mercy's Ebola preparedness team includes executives, administrators and clinicians focused on infection prevention, quality and patient safety, emergency preparedness, environmental services, supply chain, mission, communications and human resources — which includes employee education as part of its role, according to Mercy Clinical Quality Lead Frances Hixson.

Red, yellow, clearMercy Hospital Jefferson in Crystal City, Mo., put its planning into practice on Nov. 19, when the hospital received a call from the Jefferson County Health Department that a nurse who had assisted with the Ebola response in Liberia, but had no direct contact with patients, was back in the U.S. and was sick. Mercy Hospital Jefferson and health department officials previously had met to discuss protocol in case a potential Ebola patient needed to be admitted. Health department nurses had been visiting the patient for a few days at her home, but the department called the hospital once she registered a temperature. She needed to be tested for Ebola and kept in isolation until the test results came through.

Early on Nov. 20, Mercy Hospital Jefferson admitted the nurse to a freestanding 15-bed surgical center on Mercy Hospital Jefferson's campus, said Eric Ammons, the hospital's president. Patients who had been in the facility had been transferred to the main 251-bed hospital before her arrival. The patient's test results, provided to her later on the day she was admitted, showed she did not have Ebola. Since then, Mercy facilities haven't reported any other suspected cases, according to Hixson.

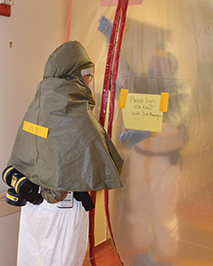

Ammons said Mercy's Ebola preparedness plan calls for the creation of "red, yellow and clear" zones in the event of the admission of a patient suspected of having the Ebola virus. Hixson explained the red zone is the patient's room. The yellow zone is a restricted patient care area where staff remove personal protective equipment and where waste management of items from the patient's room occurs. The clear zone is outside the restricted patient care area. Here staff don full personal protective equipment, access supplies and provide assistance for the team in the red zone.

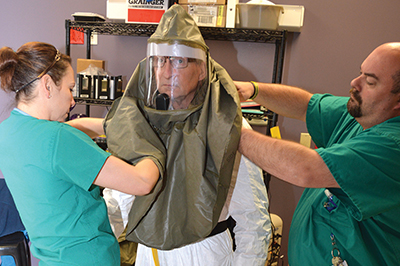

During their planning process prior to the patient's admission, Mercy Hospital Jefferson asked for staff volunteers willing to enter the yellow or red zones. Those employees received additional specialized training and repeated practice in the safe use of personal protective clothing and hoods.

Mercy's Infection Prevention, Emergency Management, and Talent Development and Optimization groups worked with clinicians to develop training about Ebola and infection prevention across the ministry. Hospital employees and those working in ambulatory care settings received foundational training about Ebola in the form of an online course last fall. Clinical staff received more detailed training about Ebola. Talent Development and Optimization keeps track of which employees have completed their assigned training. Local facilities continue to provide more training to workers about protective equipment, waste management and environmental cleaning, Hixson said.

Stocking supplies

In the weeks before the patient's arrival, Mercy's health care supply chain organization, called Resource Optimization and Innovation, dispatched infection control supplies throughout the Mercy system's four state service area. Scott Nelson, ROi's chief operating officer, said, "One real challenge was (determining) what needs to be where, and how much of it" to ship.

Nelson said Mercy's clinical leadership, using recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, determined what supplies were needed, and ROi followed their direction.

Supply chain and shipping personnel coordinated the transfer of supplies to more than 30 hospitals and hundreds of clinics and doctors' offices, Nelson said.

ROi put together response kits in a tote or a box, including hair coverings; facial protection; breathing filtration systems; gloves and impervious protective coverings for the neck, chest, arms and legs up to the knees. Nelson said ROi staff began delivering personal protective equipment to Mercy-owned facilities on Oct. 13 as part of regular supply deliveries from a center located in Springfield, Mo. ROi operates Mercy's transportation fleet, which includes more than 80 vehicles. A few special deliveries were made to respond to isolated needs.

Taking action, calming nervesNelson said the system didn’t wait until all its supplies were in hand to deliver them; it sent out items it had in stock right away.

He said every type of item needed for Ebola response was in short supply industrywide this past fall. In January, he provided an update, saying supplies had improved, though there are still "pockets where there is a national shortage of personal protective equipment."

At Mercy Hospital Jefferson, the patient tested negative for Ebola on Nov. 20 and was discharged Nov. 22. Leadership felt the Ebola preparedness worked well; Ammons said the hospital will make some communications adjustments based on the experience.

Communication lessonsAmmons said the patient had an iPad to communicate with family members and others outside the facility while she was in the surgical center. He said, in the future, such electronic devices may be provided to clinicians to communicate with each other, as they found it difficult to hear one another while in full protective gear and didn’t want to speak loudly in front of their patient. The electronic devices are decontaminated after use.

At the time the patient was admitted, the hospital had a good plan in place to communicate with current patients and their families, Ammons said. Clinicians rounded on patient floors and answered questions, Hixson said. Ammons said it took about a day after the potential Ebola patient was admitted for the hospital to set up a way for recently discharged patients to ask questions or allay their exposure concerns, and he’d like to see that communication happen more quickly in future events.