BY: RABBI DR. NADIA SIRITSKY, MSSW, BCC

Roy Scott

As a rabbi, an interfaith chaplain, a mediator, a therapist and mission leader, I have dedicated my life to healing and service. I am constantly in awe of the sacred work that happens every day in our Jewish Hospital and University of Louisville Hospital, part of KentuckyOne Health, a blended, interfaith family strengthened by its Jewish, academic and Catholic heritages and inspired by shared core values: reverence, integrity, compassion and excellence.

The largest health system in the state, KentuckyOne Health is a part of Catholic Health Initiatives (CHI). For me, to be a mission leader for the Catholic Church as a non-Catholic, working in other-than-Catholic facilities, means to help others connect to faith in their own language and then work toward understanding that the faith they experience is not disconnected from the faith of others — and this, in turn, is not disconnected from the Catholic teachings that inspired CHI to be formed.

A little history: In 2005, Louisville, Kentucky's Jewish Hospital and Colorado-based CHI formed Jewish Hospital & St. Mary's HealthCare (JHSMH). Jewish Hospital Health Services became the majority owner of the new entity, which included CHI's two Catholic hospitals in Louisville: Our Lady of Peace and Sts. Mary and Elizabeth Hospital.

This first relationship was grounded in several agreements outlined by Carl Middleton, DMin., CHI's vice president of theology and ethics, and Rabbi Chester B. Diamond, representing Jewish Hospital Health Services and the Louisville Jewish community. Together, they wrote two guiding documents, outlining ways in which the uniqueness of each entity would continue to be respected and emphasizing the common ground on ethical issues that would chart their course forward.

A NEW PARTNERSHIP

Seven years later, JHSMH came together with seven CHI-sponsored Catholic hospitals from the eastern side of Kentucky. They then formed a new partnership with a secular academic medical center, the University of Louisville Hospital and James Graham Brown Cancer Center.

As these collaborative relationships were being formed, a very public and heated debate arose in Louisville about Catholicism, women's rights and issues related to end-of-life care, as well as what the new partnership might mean for these matters.

Secular academic voices spoke out in concern about any religious overtones to the medical care provided. Jewish voices spoke out in concern about the loss of Jewish identity that this larger interfaith partnership might entail. Catholic voices spoke out in concern about preservation of its hospitals' Catholic identity in the newly formed, multifaith environment.

It took true dedication and creativity to configure the new organization in such a way that KentuckyOne Health, and specifically its downtown campus composed of the University of Louisville Hospital and Jewish Hospital, could:

- Receive a nihil obstat from the archbishop of Louisville, conditional to an annual review of the operations of the joint operating agreement for continued adherence to the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (ERDs)

- Preserve the Jewish identity of Jewish Hospital and ensure continued support from the Jewish community

- Meet the needs and address the concerns of the secular University of Louisville's academic and scientific community

EARLY CHALLENGES

Interfaith dialogue and the creation of blended families bring challenges, and KentuckyOne Health's early years are no exception. As the mission leader for the downtown campus of KentuckyOne Health, I have the unique opportunity to help build trust and healing between and among multiple communities as they grow, share best practices and develop innovative programs to care for all those in need of healing — especially the underserved that are at the heart of each hospital's founding mission.

My first task was to create and develop a mission role in two health care organizations for whom the role was a new concept, while at the same time reaching out to the broader Louisville academic and Jewish communities to build trust and establish rapport. I am so grateful to my supervisor and mentor, Brian Yanofchick, senior vice president of mission for KentuckyOne Health, as well as Carl Middleton from CHI, Joe Gilene, Louisville market president, downtown medical campus, and my fellow KentuckyOne Health mission leaders and my senior leadership team members for their wise counsel, support and encouragement, as I began to define my role.

For Jewish Hospital, the role of mission leader was a little more clearly defined, not to mention a more natural fit for me, as a rabbi. I began by sharing weekly reflections on the Torah portion, namely the Biblical passage that the Jewish community reads every week, and connecting its themes to our mission, values, program and daily activities. I was able to rely on religious rituals, symbols and language from the Jewish tradition to ground our faith-based work, while using my experience as an interfaith chaplain to ensure that we were as inclusive as possible to those of all faiths. This is not dissimilar to what my Catholic counterparts do in Catholic hospitals.

For University of Louisville Hospital, I sought to ensure that the texts and language I used were not specifically religious. Rather than prayer or sacred texts as an opening reflection, I turned to the language of mindfulness and meditation to help staff connect their work to our deeper mission. I also turned to the Jewish tradition articulated by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, active in the Civil Rights era. He emphasizes how all of us, in our diverse ways, can come together to "pray with our feet." This expression, coined when he marched in Selma, Alabama, with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, speaks to my approach to meet University of Louisville Hospital where its passion is the most fiery — namely its commitment to social justice. I seek to connect this zeal to the spirituality that is at the core of our healthy communities work and our organizational commitment to caring for the underserved, which in Judaism we call tikkun olam, the healing of the world.

RICH INTERFAITH TRADITION

KentuckyOne Health reflects the rich traditions of its founding partners as it seeks to fulfill its mission: to bring wellness, healing and hope to all, including the underserved. Like all interfaith families, we have a unique opportunity to learn from one another. In a world where religion is too often used to divide, I am excited to have an opportunity to work with my Catholic colleagues to build bridges of healing and connection and to help us begin to recognize that we are part of one human family, committed to the same sacred principles, even as we use different language to define them. Our core value is reverence, and this means that we not only need to show reverence for our own understanding of the Sacred, but also that of those around us.

One way I sought to accomplish this was to work in partnership with my fellow Kentucky-One Health mission leaders and CHI's Carl Middleton to create a new incarnation of CHI's ethics associate program that would be reflective of KentuckyOne Health's unique multifaith identity. Together, we reformatted the year-long training program to ground hospital leaders and caregivers in the ERDs, in order then to provide several panel discussions where elements of the ERDs were outlined in detail, and then expounded upon by an academic ethicist from the University of Louisville and two rabbis, one Reform and one Orthodox.

The panelists spoke to the common theoretical and theological concepts in their respective traditions. Their dialogue modeled how differences can be bridged in order to focus on common values that can guide patient care and further the mission of the organization. Program participants from all three heritages commented on how enlightening it was for them to realize that our traditions were not as different as they had initially feared. For me, this was the first step toward mission integration in an interfaith context, and it went a long way toward responding to the concerns of those who felt like an openness to Catholicism might somehow compromise their own identity and beliefs.

In Judaism, there is a practice to not write out the word for the Deity. This is done as a sign of reverence and recognition that the Holy One is greater than our limited language can begin to convey. I write "G!d" as my way of expressing my understanding that the Sacred is limitless. I believe that when I make space for the beliefs of others, I also am expressing my faith in the infinite nature of G!d.

BRIDGING GAPS

Organizationally, KentuckyOne Health has defined its core value of reverence as "respecting those we serve and respecting those who serve." As a Jewish hospital and a secular academic hospital serving a religiously diverse patient population and working with religiously diverse staff, this means recognizing that there will necessarily be gaps between our language and symbols and the spirituality of all those involved. My first task as a mission leader is to help bridge those gaps by planting the seeds of reverence in the hearts of all who serve.

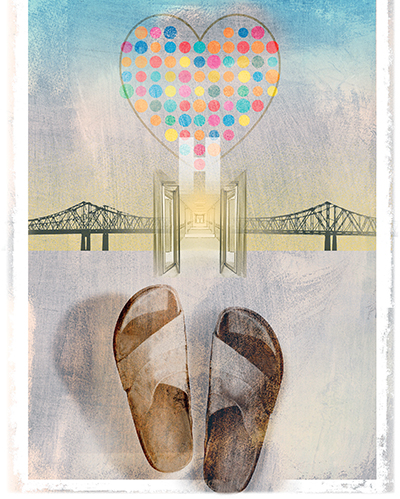

I feel like a very big part of my role is to translate: to listen to what others are saying and doing, and to help them to hear that our core message is the same. Recently, a staff member expressed to me her appreciation that I use inclusive language, rather than explicitly theistic language, when writing or speaking, so that atheist or religious alike could relate. She said this approach made it easier to remain open to the message I was trying to convey and brought to mind an anonymous composition she had read long ago. She remembered it as:

"Before approaching a different culture

a different religion

a different peoples,

Let us take our shoes off

for we walk on holy ground

Let's not forget

that God was there before our arrival."

I was deeply touched by this affirmation of my work. As a chaplain, my goal has always been to help people remember their way back to their truest and deepest spiritual selves and to sort through the conflicting messages that their life experiences may have taught them, which may have caused them to be filled with more fear than faith, more anger than love, and more despair than hope. I believe that once we are able to live more compassionately, it becomes easier to make space for reverence, both toward ourselves and toward those around us.

TRANSLATING SACRED MESSAGES

The great medieval rabbi, Rashi, commented on the passage of Deuteronomy 1:5 where Moses was explaining the Torah (Pentateuch) to the children of Israel, as they were passing over the Jordan River and preparing to enter into the Promised Land. The Hebrew word bair means to explain well, and Rashi explains that this word was used to signify that Moses translated the Pentateuch into 70 languages. The 19th-century Jewish commentary, Ktav Sofer, further teaches that the word bair is used to teach that the revelation from Mount Sinai was intended not only for the generation of the desert but for all subsequent generations, and that unless it was translated into a language they could understand, they would not be able to receive it.

The ability to translate sacred messages from one context to the next is an ancient charge, but it is also one with contemporary resonance. In particular, living in the United States in the 21st century, we are blessed to witness the diversity of our human family. Working in a faith-based hospital system presents unique opportunities and challenges to learn and grow together in our understanding of the expansiveness of our Creator, in whose image we have been created. I believe that this is at the heart of the task of the mission leader — to help those alongside whom we work to recognize the sanctity of the work they are doing.

The Talmud teaches that the Presence of The Holy One hovers over the bedside of one who is ill. When we enter to visit with a patient, it is as if we are entering into the Presence of The Holy One. This teaching informs my understanding that the hospital is sacred ground. Service in support of those who are caring for our patients is holy. Regardless of our personal beliefs or backgrounds, it is clear to me that the work we do is holy. Learning how to bridge those specific religious paradigms or languages is sacred work. If our world could learn to show reverence and respect for one another, we would be much closer to the messianic kingdom for which our religious traditions pray.

I often quote St Francis of Assisi's Prayer for Peace because I believe this is truly our ultimate task: to become an instrument of peace, and to sow love where there is hatred, hope where there is despair, light where there is darkness and joy where there is sadness. May the time come soon when we feel like we can all say Amen to each other's prayers.

RABBI DR. NADIA SIRITSKY is a board-certified chaplain, a social worker and a mediator, with a passionate commitment and expertise in working with interfaith families. She has served as a rabbi at two Reform Jewish congregations and has extensive experience in health care settings. She is the vice president of mission for KentuckyOne Health, serving Jewish Hospital, the University of Louisville Hospital and James Graham Brown Cancer Center in Louisville, Kentucky.