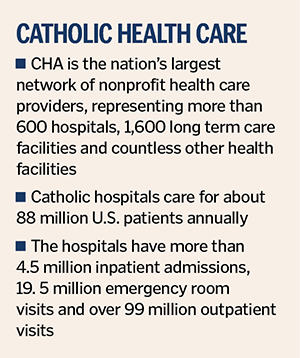

Leaders of Catholic health care are warning that proposed cuts and changes to Medicaid could result in coverage losses to millions of people, affect the overall ecosystem of health care, and take America down a "dangerous path" of reducing access for everyone.

"Congress has a moral obligation to consider the real and harmful consequences these proposals would have on our nation's health care safety net and the impact on the lives of America's most vulnerable individuals," Sr. Mary Haddad, RSM, president and CEO of CHA, said in a press call Tuesday.

She added: "Congress should not take America down a dangerous path of drastically reducing access to health care in the United States."

Sr. Mary was joined by executives from four Catholic health care systems that care for patients in 39 states and cover urban, rural and suburban areas. She pointed out that Catholic hospitals care for one in seven patients nationwide, many of whom rely on Medicaid.

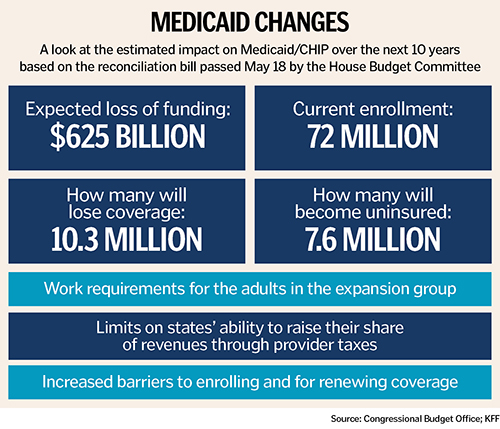

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that at least 7.6 million people will become uninsured if the budget reconciliation bill working its way through Congress becomes law. The bill cuts an estimated $625 billion from Medicaid over 10 years.

Other proposed changes are to add new work requirements, make it easier for states to cancel people's coverage, and reduce funding to the 12 states that use their own tax revenues to provide coverage for undocumented immigrants.

Other proposed changes are to add new work requirements, make it easier for states to cancel people's coverage, and reduce funding to the 12 states that use their own tax revenues to provide coverage for undocumented immigrants.

Mike Slubowski, president and CEO of Trinity Health, pointed out that cutting billions of dollars from Medicaid would hurt communities, not just those who rely on it for coverage.

"We've seen it firsthand," said Slubowski, whose system has facilities in 26 states. "When people lose coverage, they skip checkups, they stop taking medications, and eventually they show up in the ER sicker and in need of more costly care that could have been prevented. And that's not just bad for health, it strains hospitals, overcrowds our emergency rooms, and drives up costs for everyone, insured or not."

Slubowski pointed out that Medicaid coverage is a bipartisan issue. "All of the legislators, regardless of which side of the aisle you're on, have a lot of constituents that are on Medicaid," he said. "One out of every five Americans get coverage in Medicaid, and when you combine that with Medicare, another federal and public program, this is an enormous part of their constituencies."

A safety net for all

Ascension President Eduardo Conrado said 20% of the patients his system serves across 16 states and Washington, D.C., are covered by Medicaid. For those patients, he said, Ascension absorbs about 34% of the cost of care. For patients who are uninsured or underinsured, he said the system picks up 88% of the cost of care.

"For them and many others, access to health care depends on decisions being made right now in Washington," he said.

Conrado emphasized that Ascension supports efforts to remove fraud, waste and abuse, which the Trump administration has said is being targeted by the Medicaid changes. But he said the proposal under consideration would result in unnecessary red tape that would cause people to lose coverage.

"Medicaid is not a handout. It's a safety net," Conrado said. "It ensures that children, seniors, low-income families and people with disabilities get basic health care. These are not just policy issues, but they're personal that involves people, our neighbors."

Short-term gain, long-term pain

Erik Wexler, president and CEO of Providence St. Joseph Health, said that health care in the United States is at an "inflection point," facing what he called a polycrisis of inflation, labor shortages, tariffs, and Medicaid cuts. The pandemic destabilized health care in this country, and the proposed cuts could destabilize it in the future, he said.

"For potential short-term gain ... we will have long-term pain, and all of health care will be affected by that," he said.

Joe Hodges, lead regional executive for SSM Health who oversees operations in Wisconsin, Illinois, Missouri and Oklahoma, spoke about rural hospitals that are operating on slim margins or even negative ones, like 70% of rural hospitals in Oklahoma, 87% of those in Kansas, and 76% in Washington state.

He mentioned the hospital in the Oklahoma panhandle where he was born and that his mother still uses. Recognizing the vulnerability of people who live in rural areas, SSM Health now manages seven rural hospitals in Oklahoma.

"Rural health care carries the largest share of chronic disease burden in our nation," Hodges said, including a higher prevalence for obesity and premature death.

"Rural health care carries the largest share of chronic disease burden in our nation," Hodges said, including a higher prevalence for obesity and premature death.

He shared statistics related to rural populations and rural health care, such as noting that a quarter of all veterans live in rural communities and that it can take nearly three hours in parts of rural Oklahoma to drive to a hospital that provides obstetrical services.

"All these people matter," he said. "They all need to have access to care, and it is our responsibility to advocate for them, and that is why we're here today."

Seeking broader solutions

Individual systems have advocated on behalf of Medicaid in Washington, and CHA has organized collective fly-in days for health care leaders to talk to lawmakers, Sr. Mary said. She noted that while advocating on the Hill, they ran into colleagues from Catholic Charities USA who saw the proposed cuts as not just a health care issue.

"This is a social service issue, because they're recognizing the impact it's going to have on that population, which will increase their need for additional services," Sr. Mary said.

Conrado said that at the end of the day, hospitals want to keep populations healthier at a lower cost. "In order to do that, I think there's a direct relationship between the government and providers like us nonprofits to be able to incentivize keeping the population healthy and out of the emergency rooms," such as being able to provide the right medications for chronic conditions, he said.

He added: "I think the discussion beyond the cuts that are happening now is, how do we rethink population health, payment models and then partnership between nonprofits and government?"

Slubowski pointed out that Trinity Health's Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly, called PACE, is one of the largest in the country. The program includes people covered by Medicare and Medicaid. "Through outpatient day care centers, it enables seniors to continue to live at home versus in nursing homes and other long term care facilities," he said.

Slubowski said a potential means of cutting Medicaid costs without reducing access is to explore alternative finance models. "We can improve outcomes at a lower cost if providers are given that responsibility instead of working through middlemen like commercial insurance companies that first want to earn their margin," he said. "They're very adept at denying claims, frankly, of needed care that we provide to people."

Care for all

Hodges, of SSM Health, pointed out that if people lose health care coverage under the proposed changes, the health system will have to shift costs, which could mean higher commercial insurance rates on employers.

"So it just moves from one bucket to another bucket," he said. "We have to be able to shift that around in order to continue with our mission and providing services to all people that walk through our doors. Because everyone who walks through our doors, we are going to take care of them, no matter their payer, no matter where they're from. Those things are irrelevant to us. When people need us, we are there. That's why we're in Catholic health care."

Further reading: Budget plans could shrink enrollment in health insurance exchanges