SUSAN HILDEBRANDT, ROBYN STONE and NATASHA BRYANT

LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston

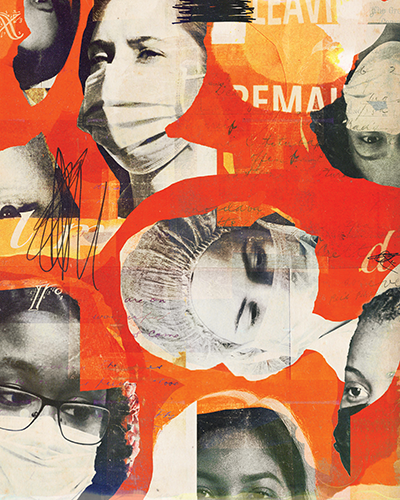

Illustration by Jon Lezinsky

The past two years will go down in history as one of the most turbulent periods that our nation — and the field of long-term services and supports (LTSS) — has ever experienced. Chief among our challenges was the coronavirus pandemic.

Tragically, the pandemic has had a disproportionate effect on vulnerable older adults living in nursing homes, assisted living communities, congregate settings and private homes. It also had a significant impact on the direct care professionals —

including nursing assistants, personal care aides and home health aides — who provide the majority of hands-on care in those settings.

A few statistics illustrate COVID-19's impact on the LTSS workforce. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the LTSS sector lost nearly 342,000 jobs from February 2020 to December 2020, a 5% decline. Jobs in nursing homes declined by 9%, followed

by declines in residential care (7%) and home care settings (3%). Direct care professionals leaving the LTSS field were more likely to be healthy, younger and white. Those who stayed on the job represented populations already at heightened risk for

contracting and transmitting COVID-19: people over age 55 and those who are Black or Latino.1, 2

Fear about contracting COVID-19 at work and spreading the virus to family members at home kept many direct care professionals from remaining on the job during the pandemic. But other factors that were evident before the pandemic also contributed to workforce

reductions and staffing shortages. Among these are childcare challenges and other personal issues that professional caregivers face.

RESOURCES AND RESEARCH

When COVID-19 became a global threat in February 2020, LeadingAge and the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston began working to find out how COVID was affecting direct care professionals working across the

continuum and to offer providers the resources they needed to support those caregivers. LeadingAge represents 5,500 nonprofit aging services providers and other mission-minded organizations, offering applied research, advocacy and education to make

the U.S. a better place to grow old.

Among our resources, the online Pandemic Playbook includes best practices, research and lessons learned by LeadingAge members as they worked to mitigate the effects of COVID-19.3 Existing LeadingAge resources, such as the Recruitment Tools

section of the Center for Workforce Solutions, also provide guidance on how LTSS providers can rebuild their workforces after the pandemic.4 This guidance includes strategies for reaching out to nontraditional populations — older

workers, individuals seeking a second career and veterans, for example — when recruiting new team members.

For research purposes during the pandemic's early days, the LTSS Center partnered with WeCare Connect, a trademarked employee engagement and management system created by Wellspring Lutheran Services, to study the impact of COVID-19 on direct care staff

working for LeadingAge providers. The study found that a substantial percentage of direct care professionals experienced a host of challenges during the pandemic, including increased workload demands and understaffing. These and other challenges were

experienced more frequently by direct care professionals at nursing homes and assisted living communities and among employees who subsequently resigned.

Our research brief, "COVID-19: Stress, Challenges, and Job Resignation in Aging Services," suggests that providers can help mitigate COVID-related stress by offering professional caregivers access to wraparound services and mental well-being support.

Flexible and creative work schedules could reduce understaffing and heavy workloads. Providers could strengthen the worker pipeline by training new cohorts to fill vacant positions.5

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Workforce challenges in the LTSS sector did not begin with the pandemic. But COVID-19 exacerbated existing workforce shortages while bringing new attention to the long-standing challenges providers face in recruiting

and retaining staff: low wages, inadequate training, few opportunities for advancement, lack of paid sick leave and other benefits. The following recommendations for action are not new. However, recent events should bring greater urgency to our efforts

to implement these recommendations.

Professionalize the direct care workforce. Our new paper, "Feeling Valued Because They ARE Valued," offers a vision for professionalizing the LTSS workforce so, just like professionals in other fields, direct care professionals would:

- Receive high-quality, competency-based training, both initial and ongoing.

- Earn a living wage and meaningful benefits commensurate with their competency level.

- Enjoy good working conditions and skilled supervision.

- Have access to a variety of career advancement opportunities.

- Be respected and appreciated by their employers, care recipients and the public.6

Increase compensation. In "Making Care Work Pay," LTSS Center researchers demonstrated that paying direct care professionals at least a living wage would provide those professionals with enhanced financial security while also reducing

turnover and staffing shortages at aging services organizations, boosting productivity, enhancing quality of care and increasing overall economic growth in communities where direct care professionals live.7 The Living Wage Calculator from

the Massachusetts Institute of Technology can help you determine the living wage in your community.8

Support mental well-being. COVID-19 highlighted the need for greater mental health support for the LTSS workforce. Rebuilding our workforce after COVID requires that we support professional caregivers as they recover from the effects

of this unprecedented tragedy. Providing access to individual counseling, support groups or workplace "de-stress" rooms represents a good start. LeadingAge also provides mental well-being resources that providers of aging services can begin using

now and continue using when the aftereffects of COVID-19 become even clearer.9

Provide wraparound services. Direct care professionals often need additional help so they can retain their jobs and be successful in their work. Providers of aging services should consider offering flexible scheduling, transportation

assistance, financial education and other strategies to help workers take care of their families and remain on the job.

CONCLUSION

The coronavirus pandemic is leaving an indelible mark on societies around the world and has

spurred providers of aging services across the continuum to become much more nimble and creative as they develop and implement strategies to strengthen the LTSS workforce. LeadingAge is committed to leading and learning from these providers so we can

work together to ensure that a high-quality workforce will meet the growing need for LTSS among vulnerable older adults well into the future.

SUSAN HILDEBRANDT is the past vice president of workforce initiatives at LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston. ROBYN STONE is senior vice president, research, and co-director, LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston.

NATASHA BRYANT is managing director/senior research associate, LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston.

Listen to the Podcast "Long-Term Care Workforce Shortages"

NOTES

- "Industries at a Glance: Nursing and Residential Care Facilities," U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag623.htm#workforce.

- Stephen McCall, "Will COVID-19 Change Direct Care Employment? New Data Offers Clues," PHI, April 12, 2021, https://phinational.org/will-covid-19-change-direct-care-employment-new-data-offer-clues/.

- "LeadingAge Pandemic Playbook," LeadingAge, https://playbook.leadingage.org/.

- "Recruitment Tools," LeadingAge, https://leadingage.org/recruitment-tools.

- Verena Cimarolli and Natasha Bryant, "COVID-19: Stress, Challenges, and Job Resignation in Aging Services," LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston, https://ltsscenter.org/reports/COVID19_Stress_Challenges_and_Job_Resignation_in_Aging_Services.pdf.

- Robyn I. Stone and Natasha Bryant, "Feeling Valued Because They ARE Valued," LeadingAge, https://leadingage.org/sites/default/files/Workforce%20Vision%20Paper_FINAL.pdf.

- Christian Weller et al., "Making Care Work Pay," LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston, https://www.ltsscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Making-Care-Work-Pay-Report-FINAL.pdf.

- "Living Wage Calculator," Massachusetts Institute of Technology, https://livingwage.mit.edu/.

- "Mental Wellbeing Resources," LeadingAge, https://leadingage.org/mental-wellbeing-resources.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSIONIn the article, "Addressing the Shortage of Workers in Long-Term Care," authors Susan Hildebrandt, Robyn Stone and Natasha Bryant describe how workforce challenges in long-term care are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. They outline

a number of recommendations from a LeadingAge LTSS Center research brief. LeadingAge, based in Washington, D.C., represents 5,500 nonprofit aging services providers and conducts research through the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston.

- Is your facility taking steps to professionalize the direct care workforce, to increase compensation, to support mental well-being or to provide wraparound services to support staff? If not, is there a mechanism in place to pursue

these changes?

- What does your staff, or you as the direct care provider, say is most needed to support resiliency and prevent burnout? Why is this important, not only to you, but for patient care?

- How has your job changed during the pandemic? Looking ahead, what systemic changes do you think are most needed to recruit and retain workers who feel valued and look forward to their work? What steps are needed to improve education

and training?

|