BY: RABBI NADIA SIRITSKY, DMin, MSSW, BCC; CYNTHIA L. CONLEY, PhD, MSW; and BEN MILLER, BSSW

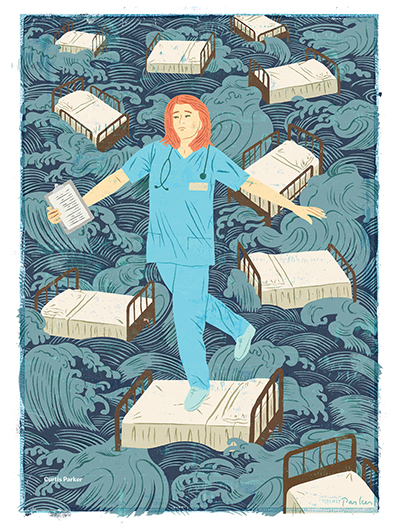

Illustration by: Curtis Parker

The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services calls pastoral care — that is, the full range of spiritual services — "an integral part of Catholic health care"1 but doesn't specify how to fulfill

it. As a result, there is a wide variation of ways that pastoral care is provided across the country, often at the expense of both staff and patients.

Because organizations tend to be subjective, decisions about staffing pastoral care departments suffer from lack of research that documents chaplains' effectiveness. The need for chaplains currently is assessed by productivity metrics that depend upon

the number of patients in the hospital, their acuity and factors connected to the hospital's mission and values. Although chaplains also provide spiritual support to staff, most productivity statistics don't measure that.

KentuckyOne Health's Jewish Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky, proposed to study the effect chaplains might have in the emergency department setting, where chaplains rarely were integrated into daily operations. This made the emergency department a perfect

"pre-test" environment in which to measure the impact of chaplaincy not only on patient care but also on staff care, which further impacts patient care. The emergency department staff had a poor understanding of the role of chaplains, and frequently

they paged a chaplain only after a death had occurred — if they paged one at all.

When the study was first proposed, the chaplains worried that the impact of their work and presence might not translate into statistical significance. This lack of confidence, along with a lack of research knowledge, may present the biggest obstacles

to self-advocacy by chaplains.

But if the profession is to survive, chaplaincy needs to embrace evidence-based spirituality as its primary language. As the research illustrates, if something is true on one level — the spiritual level, for example — then it can be translated

into another level, like statistics. Such translation is vitally important, because decisions about health care are determined by data and the people who are grounded in that "language." When chaplains can speak the same language as their colleagues,

then they will be able to more fully integrate into patient care and serve effectively and confidently.

BACKGROUND OF THE PROBLEM

There is a profusion of research in the literature on health care professionals such as nurses, who experience burnout and stress from their work. However, the canon is much smaller regarding secondary traumatic

stress that nurses can experience from working with trauma patients in hospital emergency departments.2 In a 2013 paper, researchers Kathleen Flarity, J. Eric Gentry and Nathan Mesnikoff emphasized the gap in the literature when they declared,

"Compassion fatigue is an important and often unrecognized problem that has not been thoroughly explored or quantified in a large group of emergency nurses."3 The impact that staff burnout can have upon patient experience is even less studied.

The phrase "compassion fatigue," which includes secondary traumatic stress, is a common reference in the literature and describes several challenging contributing social factors. It can be defined as "a secondary traumatic stress reaction that results

from helping a person suffering from a traumatic event."4 And researchers Crystal Hooper et al. wrote, "A nurse experiencing compassion fatigue may have a change in job performance, an increase in mistakes, a noticeable change in personality,

and a decline in health, and may feel he or she needs to leave the profession."5

In 2018, the Joint Commission issued a safety alert related to the importance of attending to "second victims," the health care providers who are most directly involved in attending to a patient's adverse event. The emotional trauma associated with the

event can have a lasting effect on the provider, including post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from an experience with medical errors.6 This dynamic contributes to compassion fatigue, which in turn can lead to further safety errors,

as well as affecting job performance, staff retention and patient experience. Nursing researchers pointed out that "understanding the linkages between caring, patient satisfaction with nursing care, and patient satisfaction with the hospital experience

is now more important than ever,"7 and "nurse caring is the most influential dimension of patient advocation and is predictive of patient satisfaction."8

Consequently, there is burgeoning interest among hospital administrators and staff to mitigate the negative effects of compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress and burnout,9 because the prevalence of these elements in their cultures and

employees ultimately presents a threat to the overall health and financial viability of these institutions.10

A leading researcher on the quality of professional life succinctly summarizes the abstractions of the strengths and challenges of providing care under two categories: compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction. She defines compassion fatigue as a

combination of both burnout and secondary traumatic stress.11 Distilling these ideas down further, burnout "describes . . . the physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by long-term involvement in emotionally demanding situations."12

Secondary traumatic stress or "vicarious traumatization" refers to the transmission of traumatic stress through observation and/or hearing others' stories of traumatic events and the resultant shift/distortions that occur in the caregiver's perceptual

and meaning systems.13

Beth Hudnall Stamm, whose work has focused on a person's strengths as a remedy for compassion fatigue, pioneered the idea of compassion satisfaction, a positive outcome for caregivers of persons with trauma. She elaborated on her concept when she likened

compassion satisfaction to "the pleasure you derive from being able to do your work well. For example, you may feel like it is a pleasure to help others through your work. You may feel positively about your colleagues or your ability to contribute

to the work setting or even the greater good of society."14

Placing compassion satisfaction in the context of hospital emergency departments, Flarity, Gentry and Mesnikoff contended that it was "the joy, purpose, and meaning emergency nurses derive from their work…"15 For example, compassion

satisfaction can result when emergency department nurses bear witness to observable improvements in patient suffering, such as the reduction of pain following the administration of medication.16 However, inherent to the brevity of nurse-patient

relationships and levels of acuity in emergency departments of hospitals, this source of positive reinforcement often is lacking. Thus, when compassion satisfaction was absent in those situations, researchers have named resiliency as a remedy, and

they defined it as "individuals' strengths and resources, both internal and external protective factors, that help a person bounce back from or thrive despite adverse circumstances.17

More than 30 years of research literature has supported the effectiveness of programmatic staff support systems.

"It is important to collaborate with human resource staff to identify psychosocial resources to support staff in constructive debriefing after especially traumatic events, as well as to anticipate the need for and provide assistance to individual staff

experiencing unusually high levels of stress," wrote Hooper et al.18 And Burtson and Stichler pointed out that "there is an opportunity for nurse managers to change direction away from educational interventions and toward interventions

that focus on reawakening the source of satisfaction that nurses derive from caring, while improving their sense of social belonging."19 Thus, there is an emphasis in the literature on staff education and evidence-based interventions for

compassion fatigue, burnout and secondary traumatic stress being combined into one modality.20

More specifically, the efficacy of staff psychosocial support interventions provided by chaplains also has been noted for decades. Because of their integration with staff, chaplains are uniquely positioned to build relationships and foster trust. Chaplains

are skilled in crisis intervention and are oriented toward whole-person care. Indeed, chaplains attend to the human and spiritual needs of employees and organizations that long to find in their work the merits of a calling, more so than simply a profession.

Using chaplaincy services for staff is efficient because the funding of these positions usually already is part of hospital budgets, and if any cost is incurred, it is minimal when compared with other professionals who have provided such support.

METHODS FOR THE PILOT PROJECT

The research project examined the impact of having a chaplain present in the emergency department, rounding on patients and staff for four hours a day over the course of three months. Prior to this project,

chaplains primarily provided pastoral care to inpatient units and intensive care units within the hospital and had minimal interactions with the emergency department.

In order to access emergency department nurses for the pilot project, KentuckyOne Health's vice president of mission worked with the chief nursing officer, along with the performance excellence coach stationed in Jewish Hospital's emergency department,

to determine parameters.

Participants were required to be full-time emergency department staff (nurses and nurses' aides both participated), and they had to have a reading comprehension above the eighth grade level. There were no personal incentives offered for completing the

survey. Procedures of informed consent were observed, and respondents' anonymity was maintained.

Participants completed a pre-test to measure levels of burnout and compassion fatigue and collaborated with a chaplain for three months. During that time, both staff and patients received pastoral counseling interventions and then took a post-test after

the intervention. The study used the Professional Quality of Life Scale, a reliable and valid barometer of levels of compassion satisfaction, burnout and compassion fatigue in employees.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of KentuckyOne Health as a quality improvement project.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

In short, the study results showed that compassion satisfaction (the opposite of compassion fatigue) went up, levels of burnout went down and symptoms of secondary trauma went down after participants talked

with a chaplain.

Note that there were several limitations to the study, and preliminary findings suggest that ongoing research is essential. The project involved a very small sample of nurses and nurses' aides. Although findings were replicated at other hospitals within

the organization, their processes varied and therefore are not reportable. Furthermore, no demographic data was collected, which would have provided additional information for some of the findings.

Still, a decrease in compassion fatigue among a sample of emergency room nurses resulting from a brief pastoral intervention represents a new way of understanding the impact of a cost-effective measure on the lives of those who make their living caring

for others. The research supports the need for nurse managers to move away from reliance mainly on educational interventions to use of interventions that highlight caring as the source of satisfaction among nursing professionals.

"It is important to collaborate with human resource staff to identify psychosocial resources to support staff in constructive debriefing after especially traumatic events, as well as to anticipate the need for and provide assistance to individual staff

experiencing unusually high levels of stress," said Hooper and colleagues.21

Chaplains are uniquely positioned to engage with staff in meaningful ways. In this manner, chaplains have advantages over other hospital staff in that they have historically "provided a trusting, confidential, and 'alongside' presence for employees" concluded

Damore, O'Connor and Hammons. It was "more financially efficient to utilize someone already professionally trained in crisis and loss and considered part of the interdisciplinary team to provide and coordinate support for other employees," they said.22

Furthermore, the increase in patient satisfaction illustrated the importance of pastoral care, not only in terms of improving staff satisfaction, which can have an indirect impact on patient experience scores, but also in terms of ensuring whole-person

care. Given that chaplains are uniquely positioned to provide counseling and support to patients who come to the emergency department frightened and anxious, contact with a chaplain provides an extra level of patient care not previously available

to patients.

In addition, the availability of pastoral services means nursing staff are able to focus on the aspects of patient care that they are trained to provide, which can increase staff satisfaction by ensuring that they work within their competencies. Working

outside of their expertise, such as providing counseling, may have added to compassion fatigue levels. By being able to refer emotional concerns to chaplains, staff were able to feel more competent and effective.

Anecdotally, members of the staff reported immense gratitude for the pastoral support. Initially, staff members were hesitant about the project, stating "I am not religious, why would I need a chaplain?" and "Unless someone dies, I don't understand how

this is helpful."

At the conclusion of the three-month project, staff wrote such comments on the post-test as "Don't take my chaplain away" and "I did not realize how much I needed this support until I got it."

Chaplaincy team members also reported a deepened appreciation for the work that emergency nursing staff performed, as well as an enhanced ability to triage patient care needs by being able to provide improved continuity of pastoral support to patients

and families.

After the study concluded, Jewish Hospital created a new chaplaincy position for palliative care needs so that the rest of the chaplaincy team could focus upon staff support as well as patient care throughout the hospital. Staff increasingly began to

rely on chaplains to debrief them after adverse events and other forms of secondary trauma. Chaplains created a new workflow process that included regular rounding in the emergency department.

The project's findings were disseminated across KentuckyOne Health, and several other emergency departments within the system — including Flaget Memorial Hospital in Bardstown, Kentucky, and Saint Joseph Mount Sterling in Mount Sterling, Kentucky

— implemented the changes. Those hospitals also reported improvement in staff morale and patient experience as a result of increased pastoral care presence in the emergency departments.

CONCLUSION

The project illustrates the statistically significant impact that chaplains can have on patient care, as well as on staff well-being. Although the trauma involved in serving as an emergency department staff person cannot

be avoided, staff compassion satisfaction levels — namely, the meaning that they ascribed to the work that they did — increased, thereby helping to mitigate against the secondary distress that can accompany caring for emergency department

patients and their families.

By having a chaplain present to make rounds and debrief staff members after difficult encounters, they were able to integrate their spirituality more comprehensively into their daily work. In addition, the chaplains provided pastoral support to emergency

department patients, helping them feel less anxious.

There is a need for future research in order to understand the most effective ways to deploy chaplains within the hospital setting and to help the hospital meet its larger organizational goals.

RABBI NADIA SIRITSKY is vice president of mission, KentuckyOne Health, serving Jewish Hospital, Our Lady of Peace and Frazier Rehab Institute in Louisville, Kentucky.

CYNTHIA L. CONLEY is assistant professor, Spalding University School of Social Work, Louisville, Kentucky.

BEN MILLER is a master's of social work student and research assistant, Spalding University School of Social Work, Louisville, Kentucky

Special thanks to the following chaplains and team members: the Rev. Dr. Frank Woggon, BCC; Kathy Lesch, BCC; and Mark Cooksey, BSME; Anne Alexandra, BCC; and William Arnold, MDiv.

NOTES

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, 5th ed., Part Two, Introduction. www.usccb.org/issues-and-action/human-life-and-dignity/health-care/upload/Ethical-Religious-Directives-Catholic-Health-Care-Services-fifth-edition-2009.pdf.

- Crystal Hooper et al., "Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Compassion Fatigue among Emergency Nurses Compared with Nurses in Other Selected Inpatient Specialties," Journal of Emergency Nursing 36, no. 5 (2010): 420-27. www.jenonline.org/article/S0099-1767(09)00553-4/fulltext.

- Kathleen Flarity, J. Eric Gentry and Nathan Mesnikoff, "The Effectiveness of an Educational Program on Preventing and Treating Compassion Fatigue in Emergency Nurses," Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal 35, no. 3 (July 2013): 251.

- Paige L. Burtson and Jaynelle F. Stichler, "Nursing Work Environment and Nurse Caring: Relationship among Motivational Factors," Journal of Advanced Nursing 66, no. 8 (August 2010): 1,821. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05336.x/abstract.

- Hooper et al., 422.

- Joint Commission, "Quick Safety Alert: Supporting Second Victims," Quick Safety, Issue 39 (2018).

- Hooper et al., 420.

- Burtson and Stichler, 1828.

- Beth Hudnall Stamm, The Concise ProQOL Manual, 2nd ed. (Pocatello, Idaho: The ProQOL.org, 2010). https://nbpsa.org/images/PRP/ProQOL_Concise_2ndEd_12-2010.pdf.

- Deborah Damore, John O' Connor and Debby Hammons, "Eternal Work Place Change: Chaplains' Response," Work 23, no. 1 (2004): 19-22.

- Stamm, The Concise ProQOL Manual.

- Hooper et al, 422.

- J. Eric Gentry, "Compassion Fatigue: A Crucible of Transformation," Journal of Trauma Practice 1, no. 3 (2002): 41.

- Stamm, The Concise ProQOL Manual, 2.

- Flarity, Gentry and Mesnikoff, 249.

- Burtson and Stichler.

- Flarity, Gentry and Mesnikoff, 249.

- Hooper et al., 426.

- Burtson and Stichler, 1829.

- J. Eric Gentry, Jennifer Baggerly and Anna Baranowsky, "Training-as-Treatment: Effectiveness of the Certified Compassion Fatigue Specialist Training," International Journal of Emergency Mental Health 6, no. 3 (2004): 147-55.

- Hooper et al.

- Damore, O'Connor and Hammons.