AGE-OLD CHALLENGE: MISSION V. MARGIN

Catholic health care has long dealt with the challenges of balancing the organization's mission versus the margin of operating a business in the 21st century. In its purest sense, the margin of an organization is what remains when expenses are subtracted from revenue. Our modern era is not immune from navigating this balancing act, primarily within emergency medicine, or in under- resourced or rural communities lacking sufficient governmental programs including shelters, subsidized housing, food banks or soup kitchens, and behavioral health resources. Moreover, this lack of support system drastically impacts individuals with low social determinants of health, such as unsheltered, unemployed, or unrepresented individuals. The Mercy Health System is commonly susceptible to this age-old problem, which causes organizational tension in stewarding a business while upholding the mission, "…[to] bring to life the healing ministry of Jesus through our compassionate care and exceptional service." Sr. Mary Roch Rocklage, RSM, aptly described the tension of mission and margin: "[w]e wouldn't be here if we didn't attend to the business…we [also] have our mission, and if we don't attend to both — if we don't do the ministry part, somebody ought to close our doors. If we aren't attending to the finances, our doors will close. So we [need to] have that healthy tension."1

We found that two hospitals within the Mercy Health System were explicitly dealing with this challenge, which affected two very different communities: one a sizeable metropolitan trauma center and the other a midsized tertiary care hospital. This discovery showed that despite the community or location, the need of this population outweighed the available support. Therefore, we found ourselves asking this question: how do we balance the social needs of unsheltered populations in an emergency medicine setting while being faithful to our mission and wise stewards of our resources?

In addition to the organizational tension around stewardship, there are burdens on the individual caregivers who find themselves struggling with conflicting interests. These caregivers desire to serve patients, and their inability to help with non-medical needs often causes moral distress. Such distress can cause resentment between the caregiver and the patient, fracturing the sacred bond within medicine. Moreover, individual caregivers want to meet the regulatory requirements set forth by EMTALA and CMS.

Oftentimes, hospitals exist in the liminal space between social support and medical support with health care. An institution needs a balance of supporting both, as such imbalances increase social or inappropriate admissions within an acute care setting. There are many definitions for social admission, but the common understanding is as follows: a hospital admission for individuals with no acute medical needs but rather social circumstances leading to a lack of support or inability to care for oneself adequately.2 There are many complications to social admissions, such as longer length of stays, over-utilization of limited resources such as staff time and attention, lack of available beds for acute medical patients, frequent readmissions, and a lack of long-term social support and follow-up for the patient with increased morbidity and mortality rates. Therefore, institutions must get creative within these tense spaces by partnering with various local specialties and community resources to maintain an ever-challenging balance.

PERSPECTIVES: METRO V. RURAL

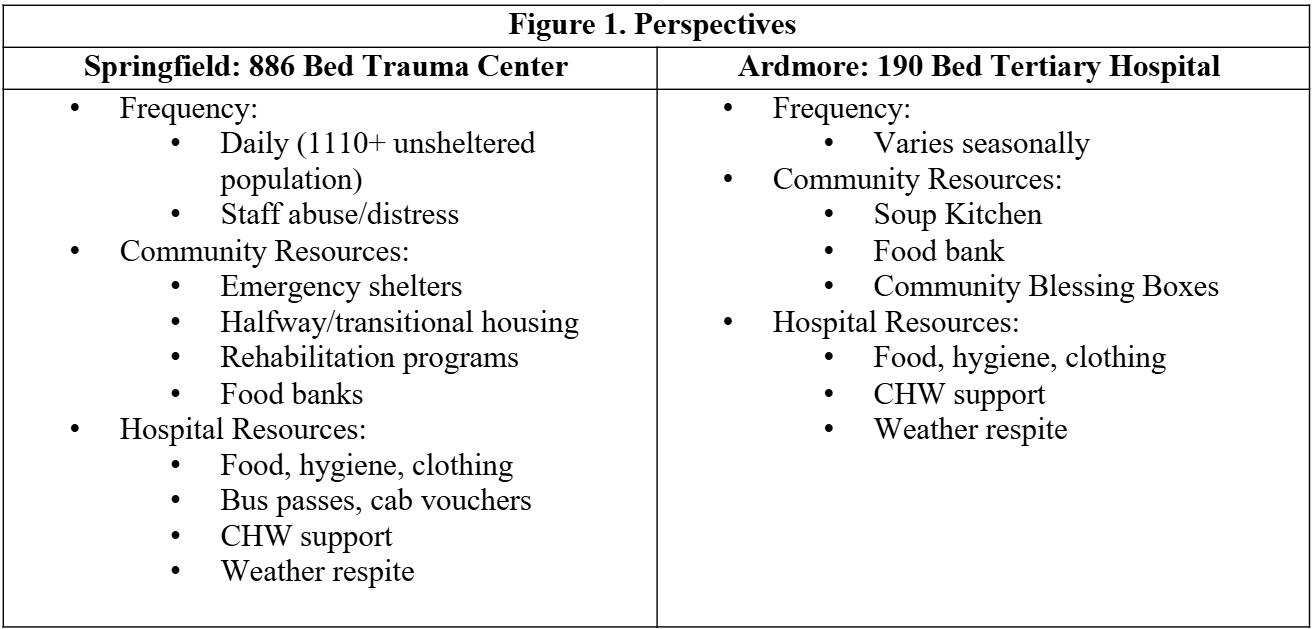

Mercy Hospital Springfield is an 886-bed Level I trauma center in a metropolitan area. Mercy Hospital Ardmore is a 190-bed tertiary hospital and a Level III trauma center in a rural area. Figure 1 shows some of the differences faced by the Mercy Springfield and Ardmore hospitals with regards to the frequency of encountering unsheltered persons and the community and hospital resources available to refer them to.

SOLUTIONS: METRO V. RURAL

Due to the differences in environment and available resources, the approach to unsheltered persons presenting to the Emergency Department had to be different. For instance, while there is a greater volume of unsheltered persons in the Springfield area, along with more violent offenders, compared to Ardmore, there are fewer community resources available to support this population. Thus, Ardmore discovered they had to meet needs that were going unmet. Both hospital settings required education around appropriate medical admissions and expectation setting with emergency medicine caregivers and the unsheltered persons seeking aid. Of critical importance throughout creating and operationalizing the solution was the involvement of key stakeholders. The stakeholders were similar at both locations. They included Finance, Legal/ Ethics, Case Management, Dietary, Public Safety, ED Leadership (Physician/Nursing), Behavioral Health, Mission, and Mercy Health Foundation.

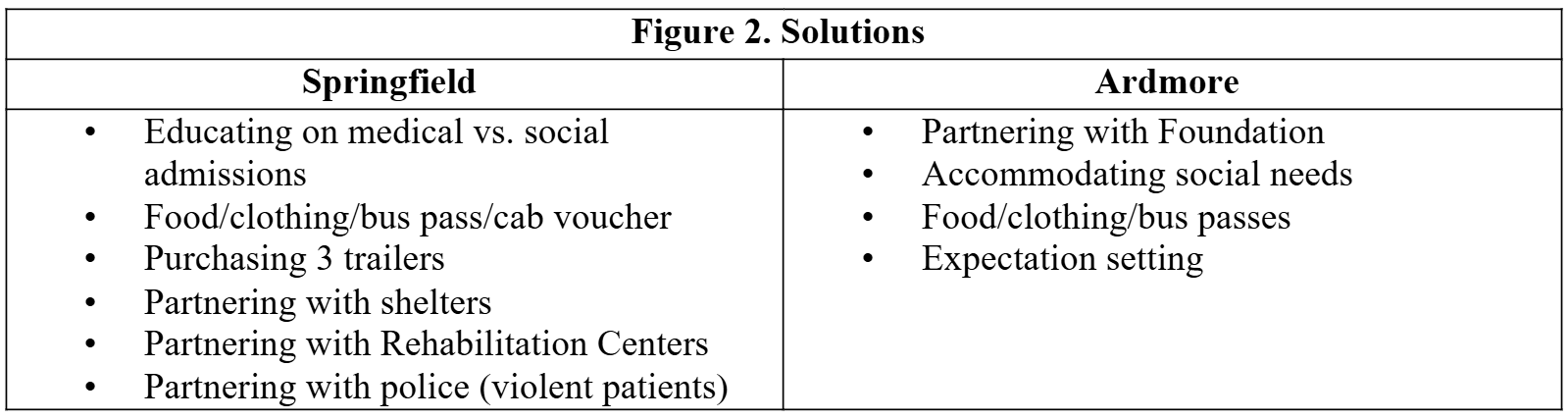

Figure 2 depicts some of the different solutions from collaboration with stakeholders to provide the best care for this patient population. Springfield's solutions centered around involving appropriate partners within the community to support these patients in finding assistance outside of the Emergency Department. Of note, is the partnership with the hospital's Foundation to acquire three trailers at a strategic location within the unsheltered campground supported by a groundskeeper to provide temporary housing for unsheltered patients cleared of acute medical needs without a safe place to discharge. If available, the unsheltered person would receive a cab voucher and a ticket to one of the trailers to spend a night out of the elements with a boxed meal and water. At Ardmore, the Foundation helped with transportation costs through paying for taxis or bus passes.

The ethicist's role varied. At Ardmore, Addison was involved from an administrative approach, offering support where department leaders needed it and guidance regarding expectation setting. At Springfield, Amanda played a dual role of administrative support by creating a task force of key stakeholders to develop strategic initiatives, education, consistent and trackable goals among leadership, and flowcharts on appropriate admission criteria, as well as being a consultant for one-off cases.

LESSONS LEARNED

One of the most important lessons learned in navigating this challenge was that we would have to make hard decisions about caring for people on this side of the Kingdom. One of the fundamental challenges will constantly be navigating the delicate tension of mission and margin, as the Sisters of Mercy before us. As we strive to innovate in areas like this, progress will often be hard-won and certainly be iterative. Neither of us has this challenge solved in our respective locations, and we never expect to. Another key lesson learned throughout this process was hospitals cannot be all things to all people. They must rely on community partners (where able) and work within the community to support (but not own) initiatives that help address social needs.

AMANDA ALTOBELL, MTS, PHD(C), HEC-C

Director of Ethics

Mercy Hospital Springfield

ADDISON TENORIO, MA, PHD(C)

Executive Director of Mission

Mercy Hospital Ardmore

ENDNOTES

- Sr. Mary Roch Rocklage, RSM, "Sr. Roch Presentation to Integrated Marketing All Team 2018," September 14, 2018. Mercy Health Archives. St. Louis, MO.

- Melissa K. Andrew and Colin Powell, "An Approach to 'The Social Admission,'" Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine vol. 10, no. 4 (2015): 20-22.10f29634c326c00e5edf17f5fbb06a7c83ae.pdf