Sometimes, a dying person doesn't have a family. Other times, they're estranged. Sometimes, a dying person's family lives across the country and can't be at their side. Other times, the family simply can't handle being there.

No One Dies Alone volunteers don't care about why. If a dying patient is alone, they want to be there.

"We're trying to bring as much compassion and love to that circumstance that we can, and that's the most we can offer," said Shawn Kiley, chief mission integration officer and executive sponsor of the No One Dies Alone program at Providence Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center near Los Angeles, a part of Providence St. Joseph Health.

The program relies on trained volunteers to take shifts to sit at a dying person's bedside. They read aloud, pray, play music, and watch for changes or signs of distress. Most importantly, they provide a compassionate presence.

"There's dignity and love, even in death," said Kiley. "How can we provide that and make that happen?"

Sandra Clarke, then a PeaceHealth nurse in Eugene, Oregon, started the No One Dies Alone program in 2001 after she was called away from the bedside of a dying man who had no visitors, and she missed the moment he died. The concept has since spread worldwide, although hospitals have various approaches and names for their programs.

"Death is the second most natural part of life. Birth and then death. It's a continuum. I think we've lost the interest in that last portion — it's treated as a failure or something to be ignored," Clarke said in a 2008 interview with Nurse.com.

Companionship beyond the dying

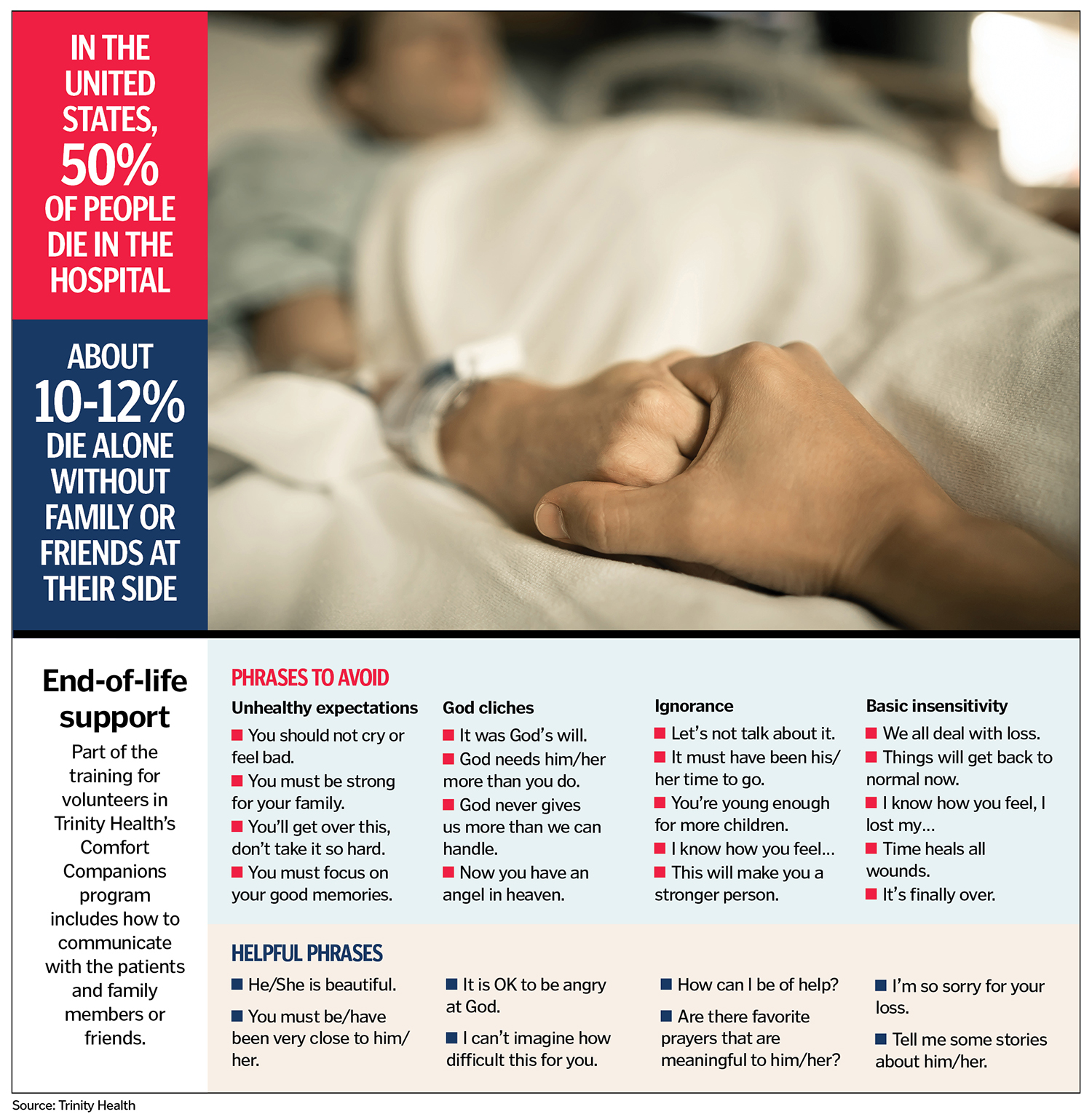

Barbara Stephen is the head of the volunteer department and a bereavement specialist for Trinity Health Oakland and Trinity Health Livonia in Michigan. She started the hospitals' Comfort Companion program in 2005 after her mother's death from cancer the year before. While she visited her mother in a hospice, she noticed that other dying patients didn't have friends or family. When her mother was sleeping or had visitors, Stephen slipped out to sit with them.

The Comfort Companion program is not just for the dying — it's also for patients who likely will recover but have nobody to sit with them, she explained. A volunteer might talk with or read to a patient. The companions also stay with patients whose family members simply need a break.

My big thing is I want family to be family," Stephen said. "I don't want them to be a caregiver during this time. So let us take that burden and just be with your loved one."

If a companion is needed, hospital staff and palliative care teams contact Stephen, who consults her roster of about 40 volunteers.

Most of the patients referred to the program are in a comatose state when their companions arrive. Still, the volunteers try to learn as much about the patients as they can, including their spiritual beliefs or religious background, so they can respond appropriately.

Stephen remembers asking the daughter of a dying man what she remembered about him growing up. The woman replied that he never missed a day reading The Wall Street Journal. Stephen arranged for volunteers to read that newspaper to him over the three evenings they sat with him. When the woman saw Stephen next, she burst into tears. Stephen thought something was wrong.

"It was perfect," the daughter said. "I walked in this morning and one of the gentlemen was reading The Wall Street Journal to him."

Stephen trains volunteers and coordinators around the country and happily shares her materials. She teaches volunteers to always introduce themselves even if the patient isn't awake, because often patients can hear. She asks volunteers to keep an eye out for any signs of distress so they can call staff. They don't provide medical care but can moisturize a patient's lips or cool them with a washcloth. They may hold a patient's hands unless the patient withdraws.

"For as many times as I have done it, it is very fulfilling, because we find out that especially those that have no family, it's like they really want to be remembered," Stephen said. "That's the one thing that we always reassure them: that they will always be remembered."

Connecting through stories

Colleen Storey is the holistic care supervisor of PeaceHealth Hospice based in Vancouver, Washington. Its No One Dies Alone program extends to hospice and community settings, including assisted living and skilled nursing facilities.

Storey didn't know Clarke, who also worked for PeaceHealth. Storey and her supervisor launched their program in 2017 after seeing it at work elsewhere.

When she trains volunteers, she pairs them off and asks them to imagine and share what their deathbed scene looks like. At first, they are somewhat appalled by the notion, but Storey presses them. At the end of the exercise, she asks for a show of hands: How many of you were in pain? How many of you were alone?

"Not one hand goes up," she said.

She shares stories with them, to make the prospect of sitting with the dying less intimidating. There was the elderly man who told Storey about fishing with his granddad when he was a boy. Then he leaned back in bed and looked toward a corner of the room. "Yes sir, I'm ready," he said. Storey asked who he was talking to, and he said, "Granddad's right here." The man leaned back against his pillow, shut his eyes, took a breath, and died.

Storey stayed with an elderly woman who was unconscious and actively dying. The woman had a favorite grandson who was an archaeologist working at a remote site in China. As the grandson made the five-day trip back to the United States, Storey and the woman's daughter assured the dying woman he was on his way.

The door finally opened, and the grandson came in, wearing his archaeologist's hat and clothes. "It was like a scene out of Indiana Jones," she said. The grandson told his grandmother he was there. The woman gave the slightest smile, took a deep breath, and died.

The PeaceHealth Hospice program has about 90 volunteers. "It changes us in such deep, profound ways," said Storey. "We have volunteers who have done this for a while, and they say, 'The gifts I have received far outweigh what I do.'"

Employees as volunteers

Kiley said Providence Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center would like to expand its program to serve people who need companionship but aren't necessarily dying. The program's roster is mostly hospital employees — executives, food and nutrition service workers, and care providers — who often go into volunteer mode before or after their regular shift. They keep a journal that serves as a record for the next volunteer. It might contain personal information about the person and what happened on the shift. If there are family members, the journal is given to them as a record of the person's final days.

"When there's family involved, I think it's healing for them to know that there's somebody with their loved one," said Terry Lucas, a nurse manager at the hospital who volunteers for the program. The staff appreciates knowing someone will be with their patients, too.

Lucas became a nurse during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and saw many young people with no one at their bedside in their final hours. "I've just always been very sympathetic to somebody dying alone in the hospital," she said.

Sitting with a dying patient compels her to reflect on life and the patient's circumstances. "I guess we all help people in other ways, but this, we get to help people in very vulnerable times," she said.

Kiley pointed out that no one is born alone. "And I think that as a human being, that speaks to us as caregivers and as humans, just to say we can do better," he said. "Let's provide some compassionate presence."