After a study confirmed that hypertension during pregnancy has a connection to heart issues later, a team at Intermountain Health developed a care model to break the link.

Dr. Kirstin Hesterberg, a cardiologist at Saint Joseph Hospital in Denver who specializes in cardio-obstetrics and a contributing author on the study, said its findings have "the potential to impact so many women." She said the findings disprove the assumption by some doctors that conditions like preeclampsia and related risks go away after a woman gives birth.

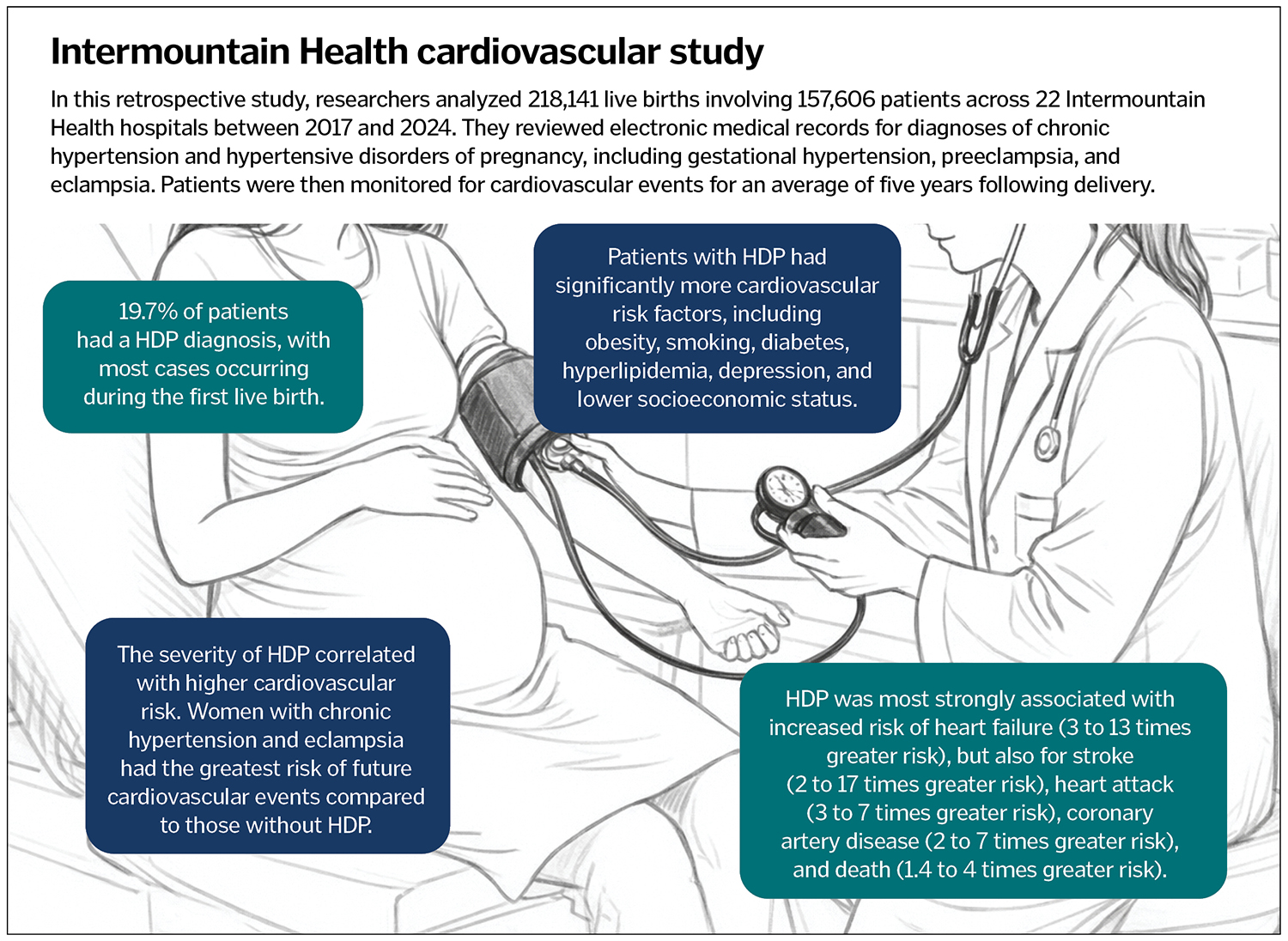

The study was presented in November at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. Among its findings were that within five years of giving birth women who had blood pressure disorders during pregnancy faced increased risk of heart failure (3 to 13 times greater risk), stroke (2 to 17 times greater risk), heart attack (3 to 7 times greater risk), coronary artery disease (2 to 7 times greater risk) and death (1.4 to 4 times greater risk).

"At least in one of the groups, women who had eclampsia, the most severe form, had almost a 20% increase in their risk of developing a type of heart disease afterwards," Hesterberg said. "These are small numbers, but that's a pretty significant increased risk for women."

The records the team looked at were from 218,000 live births at 22 Intermountain Health hospitals. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy affected nearly 20% of the more than 150,000 women who gave birth and most cases occurred during the women's first live birth.

A clear plan

After the study confirmed their suspicions about the heart risks linked to hypertensive disorders in pregnant women, the Intermountain group developed an innovative clinical care process model. The model brings together women's health providers, pharmacists, and heart and kidney doctors to proactively identify and address hypertension issues in women during and after pregnancy.

The care model outlines clear touchpoints where doctors should contact patients with high blood pressure conditions. It calls for a blood pressure check through remote monitoring within 72 hours of birth, and again seven to 10 days after discharge from the hospital. Blood pressure is also monitored at the mothers' postpartum visits, recommended at four to six weeks. Patients with hypertension will get follow-up visits for a year to help identify and address risks like diabetes, obesity and high cholesterol.

Part of the care model ensures different care providers are looped into a woman's health condition even if that patient is no longer having babies. "It's a flag for everybody who sees them after that, hey, they had this condition during pregnancy, we need to automatically pay attention to it," Hesterberg said.

The American College of Cardiology published a Postpartum Hypertension Clinic Development Toolkit as Intermountain was developing its care process model. Hesterberg said the tool kit, which Intermountain used as a resource, had many similarities and overlaps with the care model the system had in development.

Communicating with patients

In their research, the Intermountain caregivers found that compared to other patients, those with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy had "significantly more" cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, smoking, diabetes, high cholesterol, depression, and lower socioeconomic status.

Under the care model, doctors check in with patients about those and other risk factors, such as activity levels, and advise on healthy changes. For example, for patients who have little time for workouts, Hesterberg offers encouragement that moderate activity is beneficial. "I really try to tell patients, if you're walking 30 minutes five days a week, you are doing enough to have a benefit to your heart and really, actually help lower your risk of long-term heart disease," she said.

Intermountain's increased attention to high blood pressure and related risks is already helping. Hesterberg spoke of patients in their 20s and 30s who had blood pressure issues that other doctors had not traced to a cause. When discussing their medical history, the patients revealed they had severe preeclampsia when delivering their first children, and doctors had not warned them of any long-term effects.

"And I said, 'I think this is why you have high blood pressure now.' And luckily, we were able to get ahead of it," Hesterberg said.

Another patient who had high blood pressure during her first pregnancy talked to Hesterberg about minimizing her risk of recurrence while planning for a second pregnancy.

She said knowing why the symptoms are occurring comes as a relief to patients. "I think sometimes women are really good at saying: 'Well my blood pressure is high because I'm too stressed out, I'm not doing the right things, it's therefore my fault.' As opposed to: No, there's a medical condition that happened that is most likely contributing to this," she said.

Hesterberg said doctors can do a better job in general assessing risk and treating women for heart disease.

"It's also a really important point for women (to know) about their own health and knowing their own health risk, but then also providers, that we need to take women seriously when they're having any kind of symptoms," Hesterberg said.

The extra attention given to mothers is just one way Saint Joseph Hospital fulfills its mission as a Catholic health institution, Hesterberg said.

"One of the big reasons I really like working at Saint Joe's and working for this organization is we take care of people, regardless of background, of ability to pay," Hesterberg said. "It's really about: How do you do the right thing for people? From a moral, spiritual perspective, that's really fulfilling to be able to say yeah, we need to do this because it's the right thing for people."