Earlier this year, when the Trump administration pushed out its action plan for artificial intelligence, Dr. Brian Anderson said he was excited by one specific point in the document.

The plan said that winning the AI race would "usher in a new golden age" of national security, economic competitiveness, and human flourishing.

"And many folks who were in politics, I think, honestly, were scratching their heads," he said. "What is human flourishing?"

But he and many others at the nonprofit he leads, the Coalition for Health AI, are working to advance human flourishing in the age of AI.

Anderson broached the topic in a webinar Dec. 2 that was the last in a four-part series on AI ethics in health care, jointly sponsored by CHA and the Center for Theology and Ethics in Catholic Health.

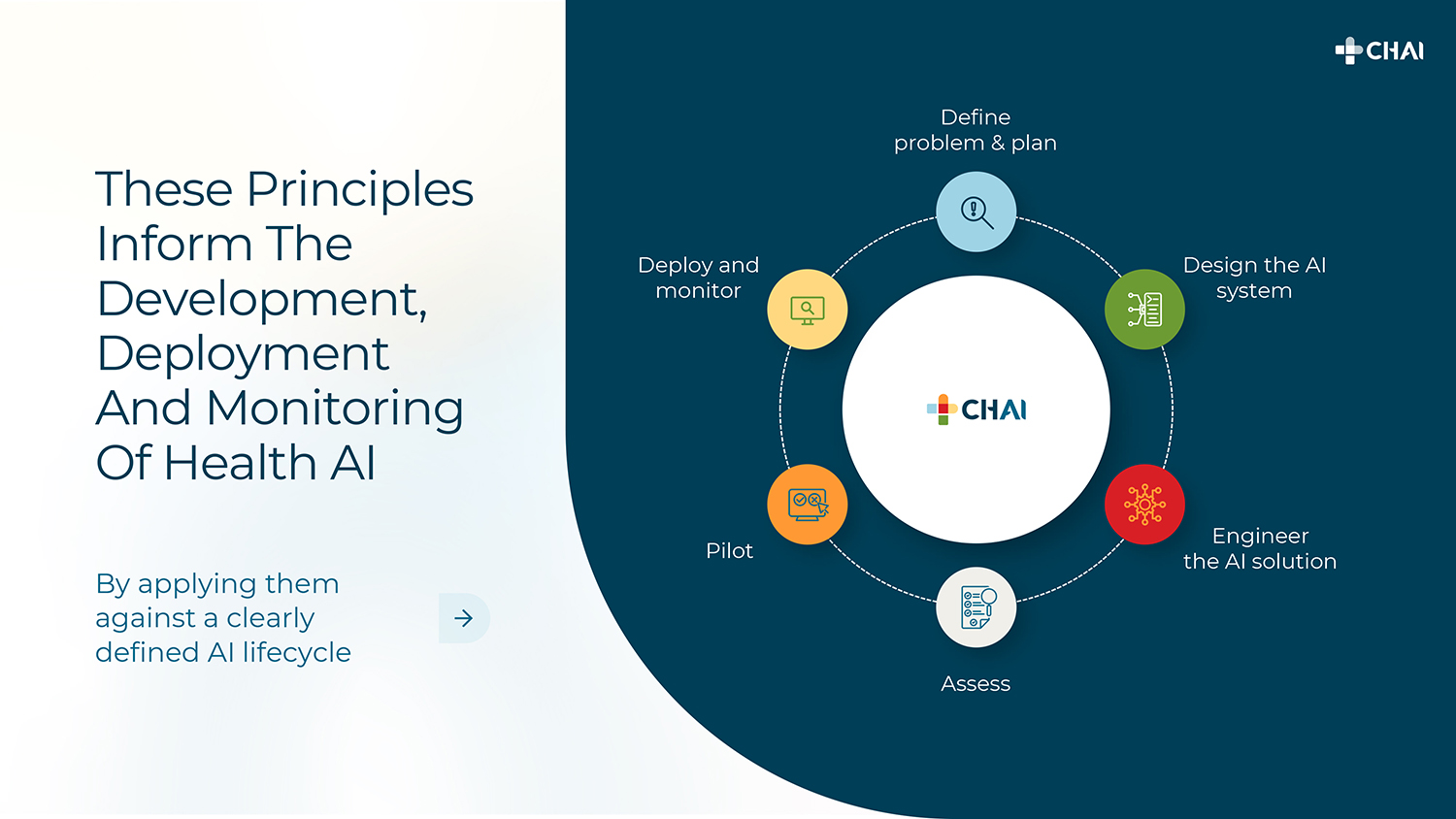

Anderson is the CEO of the Coalition for Health AI, or CHAI, which he cofounded in 2021. The group is working to develop a set of guidelines and best practices for responsible AI use in health care as well as to support the ability to independently test and validate AI for safety and effectiveness, he said.

The coalition has grown from eight organizations to more than 3,000. About 220 health systems are a part of the network, as well as about 700 technology startups.

Anderson cofounded the nonprofit during the COVID-19 pandemic. He had led data analytics for Operation Warp Speed, an effort among the private and public sectors to speed up the development of the COVID vaccine.

"And it was in that setting that we began asking if there is something more that we can be doing beyond the pandemic," he said.

When the nonprofit looked at AI, Anderson said they came back to the same question: "Do we have consensus at a technically specific level to define what responsible, trustworthy AI in health care looks like? The answer we quickly came to is we don't."

At a higher level, there is "very strong" agreement around some of the principles and ethics of health AI, he said, but the nonprofit didn't have a consensus at a technical level that would be helpful enough for a software developer or a health care system deploying an AI model.

"What exactly does that mean for governance and monitoring of these tools longitudinally?" he asked.

Using AI responsibly

Anderson discussed principles of responsible AI: usefulness, fairness, safety, transparency, security and privacy. A provider might not use an AI tool on an electronic health record if it pops up at an inopportune time, he said. "This is an example of human cognitive bias," he said. "It doesn't matter if it's the best recommendation since sliced bread, it's not useful."

He spoke of an AI company that developed a tool that reads EKGs as part of the process to predict whether a patient is at risk for a recurrent heart attack and should be kept in the hospital for observation. The company claimed the tool had a 95% accuracy rate across all populations, but the company had only trained the tool on predominantly white, highly educated people.

The model was far less accurate for minority populations because it hadn't used their data, he said. That's why it's important to know how and why the models were built, he said.

Developers can come up with guardrails — he knows of one developer that has a 12,000-step checklist — to make sure AI models align with what people believe their values to be, such as not hurting others or themselves, he said. But you can't account for every unintended consequence, Anderson said.

"We want these tools ... to ultimately be aligned to our common definition of human flourishing, and that is, I think, part of the huge challenge that we're facing," he said. "If I'm being honest with you, I would tell you that those of us in this space don't have a real understanding about how to train these models in such a way that they are aligned to our human values, as you and I might understand living a principled, value-based life."

Educating others

CHAI is working on a "nutrition label" of sorts that people using AI programs can reference to learn about things like data sets used to train the model, results of model testing, and ethical considerations. CHAI also is working with medical societies and patient advocacy groups to build educational content on how to make decisions about utilizing tools. Doctors wouldn't use an adult stethoscope on a baby and vice versa, he said. "Every day, providers are now going to be faced with having a patient in front of them and having an AI tool and not knowing, is this the right AI tool for the patient in front of me?" Anderson said.

He added that knowing the answer takes education, an understanding of ethics and AI, and time to sift through the information to make thoughtful, informed decisions.

He closed with the story about the invention of the sewing machine in the 1860s, which transformed how clothing and textiles were traditionally made by women in their homes. It disrupted an industry, created a new opportunity, and enabled women to participate more broadly in society because they had more time, he said. Many historians say the invention of the sewing machine led to the women's suffrage movement, because women became more involved in policy and politics.

"My hope certainly is that AI will empower us to live more complete, more fulfilling lives," he said. "The challenge is there's going to be massive disruption. How do we responsibly navigate that? How do we ensure we are not harming our patients? These are questions I don't have answers to. It is something I deeply believe that's going to take a whole of our community to do."