Les Hirsch was only seven days on the job as president and CEO of Touro Infirmary in New Orleans when it became apparent that Hurricane Katrina was headed straight for the city.

"I literally made the conscious decision and thought through that I was just going to step up and lead," Hirsch said. "It didn't matter if I was there five days, seven days, or seven years, that if I didn't actively step up and actively lead the team, then how could I ever be the leader of that institution?"

Hirsch is now the president and CEO of Saint Peter's Healthcare System based in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Twenty years after Katrina hit on Aug. 29, 2005, he shared leadership lessons he's taken from being at ground zero of the disaster. The Category 5 hurricane caused more than 1,800 deaths and an estimated $108 billion in damage, according to the National Weather Service.

At Touro Infirmary, patients and staff members and their relatives, about 2,000 people in all, sheltered in place as the storm struck. The Jewish hospital, in operation since 1852, is near New Orleans' famous Garden District. The storm hit in the middle of the night and the hospital went on emergency power, so not all areas were operating. By morning, the storm had passed, the sun came out around noon, and people began to leave.

"We really thought we dodged a bullet," Hirsch recalled.

The following day, word came that the levees were breaking and the city began to flood. The hospital's generators began acting up, possibly because water or contamination got in the fuel lines. Elevators began to fail. "It was very clear within a couple hours after that we were going to be subject to a complete failure," Hirsch said. "It was like a ship going down."

Seeking advice

New Orleans had very limited communication — cell phones and many telephone lines weren't working — but somehow, the pay phones in the emergency department were functioning. Hirsch called the president of the Louisiana Hospital Association, John Matessino, who helped him coordinate evacuation efforts. Hirsch had sought out Matessino's advice during his job interview process.

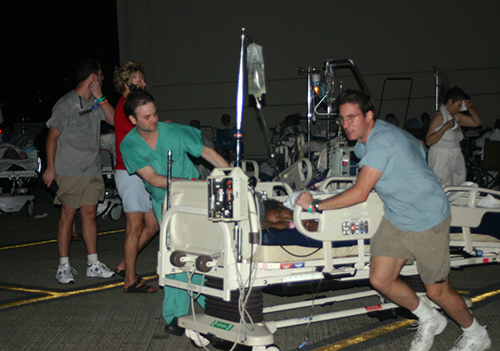

The hospital evacuated 240 patients, including 13 babies from the neonatal intensive care unit, mostly by helicopter and some by ambulance. Paper medical records went with each patient.

Because of its higher location, Touro Infirmary was not hit by floodwater, though it did sustain damage from the storm. It was the first hospital in the area to reopen 27 days later, and its adult acute care unit was the only one operating in Orleans Parish until February 2006, Hirsch said.

"We immediately moved from disaster to recovery," he said.

Touro Infirmary patients had been transferred to other areas, even out of state, and staff had dispersed. Hirsch and hospital leaders had an emergency website built to communicate with the public and staff. For staff who left the city, the hospital continued their pay and allowed them two months to decide whether they would return.

The hospital first reopened its emergency department and 50 beds, and then by spring 2006 was once again a busy hospital with about 250 patients.

New staff came from other hospitals that had been more heavily damaged or closed by the hurricane. "Now Touro became a melting pot of all staff," he said. "Not only did we have to rebuild economically and restore our operations fully, but from a cultural standpoint, we had to welcome people."

He distinctly remembers telling staff during a town hall meeting: "We have to forge a new culture that will be the new Touro culture."

"That was definitely a challenge," he said. "But the very first thing you have to do is to recognize that and then work on it and in a very transparent, intentional way."

New challenges

Hirsch stayed at Touro for three years before becoming president and CEO at Saint Clare's Health in Denville, in his home state of New Jersey. In 2015, he joined Saint Peter's Healthcare System as president and added CEO to his title in 2017.

During that time, he has navigated other disasters as a hospital leader: Hurricane Irene that hit the northeast in 2011, Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. While the pandemic lingered for years, so did the impact of Katrina, he pointed out. "The immediacy of it was there," he said. "But for the three years that I was in New Orleans, Katrina never went away."

He's learned to endure difficult situations by not getting caught up in the emotion of the moment, whether that be anger, worry or sadness.

"When you get into a tough situation, you have to be able to problem solve critically, think about the situation, and remain as calm as you can," he said. "It's not to say that I don't get that feeling in my stomach either. I'm human. But you can't allow yourself to get carried away by emotion."

He credits sports, especially playing basketball in college and into adulthood, with giving him a strong sense of tenacity, mental toughness and discipline.

"I know about digging down into the pit of your belly to not give up," he said, "and always fighting even when it's rough, when you just think that you can't go on any further."

Further reading:

Remembering Hurricane Katrina 20 years later: A look back at coverage in the Sept. 15, 2005, edition of Catholic Health World.