Dr. Paul Berndt enjoys looking around the field at his son's T-ball practices in Parkston, South Dakota, and seeing how many players he delivered.

"In a small town, it gets to be a pretty small little network," said Berndt, an obstetrician and family practitioner.

The population of Parkston is just over 1,500 people and Avera St. Benedict Health Center, where Berndt practices, sees about 60 deliveries a year. Berndt says the residents of Parkston are grateful for his services and trust Avera St. Benedict for their care.

"I think to continue to do obstetrical care, you have to have a lot of community buy-in," he said. "If those patients don't trust the care in their local facility, if they're going to drive right past that to the next facility, a lot of times that leads to programs not being able to sustain."

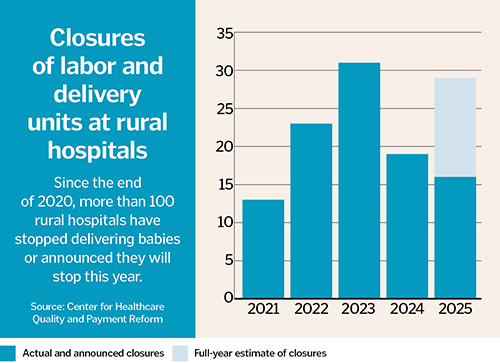

Finding obstetric care in rural regions such as the one that surrounds Parkston in Eastern South Dakota is getting more difficult. The Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a national policy center, says that since 2020, more than 100 rural hospitals have stopped delivering babies. The reasons are many, experts say. They predict the recently passed federal budget bill will be another.

Maternity care deserts

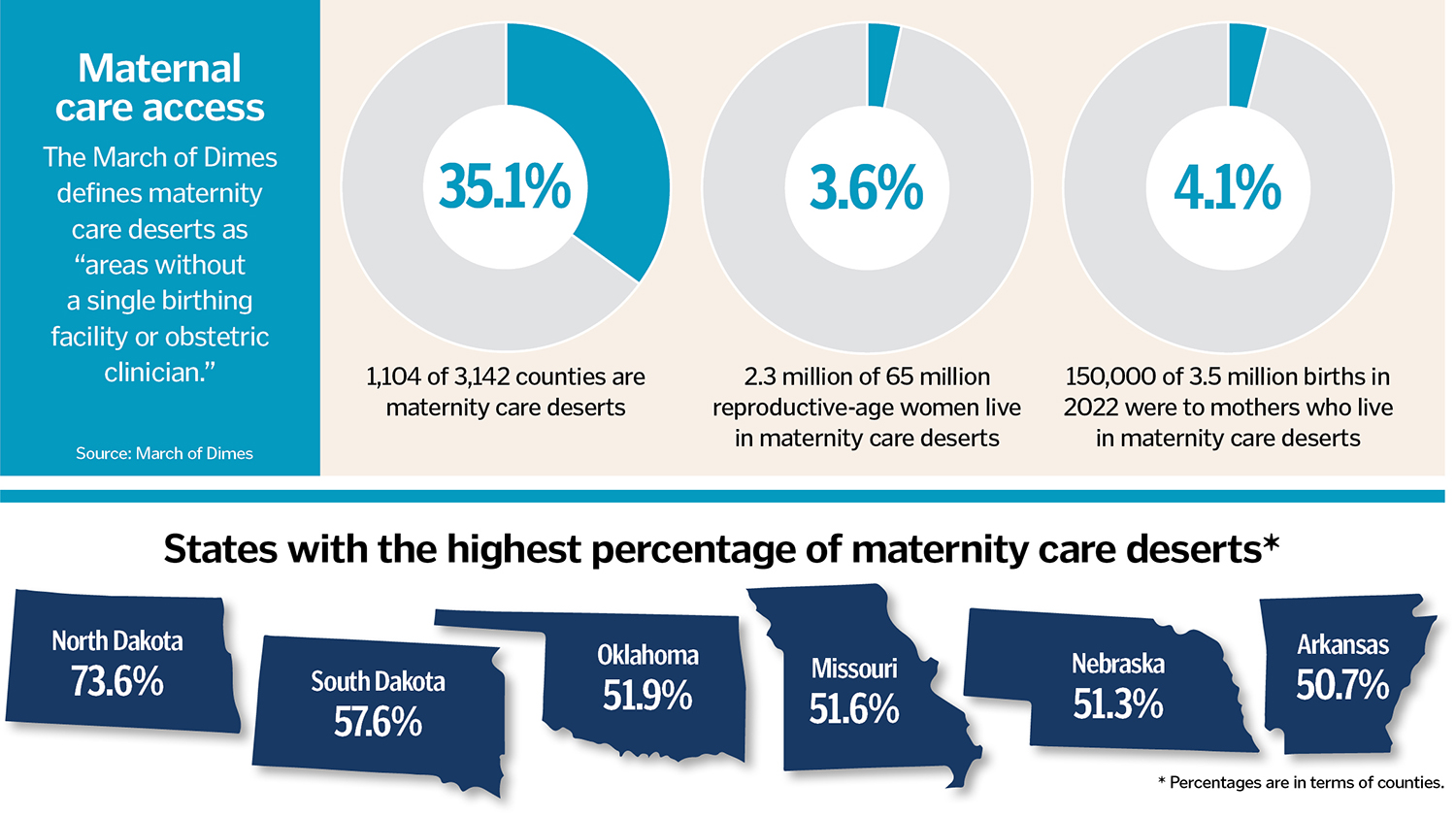

Already, some of Berndt's patients drive as far as 90 minutes for an obstetric appointment. In South Dakota, nearly 58% of counties are defined as maternity care deserts, compared to about 35% of all counties in the United States, according to a March of Dimes report. The report bases its definition of a maternity care desert on three factors: the ratio of obstetric clinicians to births, the availability of birthing facilities, and the proportion of women without health insurance.

Nearly 24% of women in South Dakota had no birthing hospital within 30 minutes compared to nearly 10% of women nationwide.

South Dakota is among the top six states in terms of percentage of counties that are maternity care deserts, in company with North Dakota, Oklahoma, Missouri, Nebraska and Arkansas.

Women living in these deserts "have poorer health before pregnancy, receive less prenatal care, and experience higher rates of preterm birth," said the report.

Women living in these deserts "have poorer health before pregnancy, receive less prenatal care, and experience higher rates of preterm birth," said the report.

With rural hospitals already running on tight margins, hospital administrators are worried about the tax package signed July 4 by President Donald Trump that will cut more than $1 trillion in Medicaid and other health care spending over the next decade, although the measure does include a $50 billion fund for "rural health transformation."

"We know that it's going to be devastating," said Ashley Stoneburner, director of applied research and analytics for March of Dimes, which operates mobile health centers for maternity care in underserved areas.

Stoneburner said the March of Dimes is looking at the potential impact of the budget bill on hospitals and whether it will lead to closures and more maternity care deserts. "We don't know how each state will handle the changes, but we're worried that states that already have the worst outcomes will have even worse," she said.

The cost of obstetric care

Workforce shortages and payments from both commercial health insurance and Medicaid programs that are lower than the cost of delivering the services have contributed to closures of obstetric units. While expanding and extending Medicaid has helped, according to the March of Dimes report, one in every 25 obstetric units in the United States has closed in the last two years and already over half of counties lack a hospital that provides obstetric care.

"It's an unusually difficult service to have because it's a 24/7 service that requires multiple types of clinical professionals to be available for every birth," said Harold Miller, president and CEO of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform.

For a hospital to provide labor and delivery service, a physician who can perform cesarean sections, an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist, and obstetric nurses must always be available. Miller pointed out that with birthrates going down, the fixed cost of having all these clinicians available at all times is causing the average cost per delivery to increase, and many health care plans already don't reimburse hospitals adequately.

A bill called the Supporting Healthy Moms and Babies Act that a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced in June would prevent private health insurance companies from requiring parents to share the costs of childbirth and related maternity care. Miller pointed out that the measure doesn't ensure that providers will get adequate reimbursement for the cost of the care.

Although adequate reimbursements would enable many small rural hospitals to keep their obstetric units open, Miller noted that many larger hospitals close their units "not because they're being forced to do it, but simply because they don't want to continue providing an expensive service that is difficult to staff."

A 'gutted' safety net

Nationwide, 23.3% of women of childbearing age in rural areas are covered by Medicaid, compared to 20.5% of women in metro areas, according to the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy Center for Children and Families.

Elisabeth Wright Burak, a senior fellow with the center, said Medicaid pays for nearly half of births in rural areas. How the upcoming cuts to Medicaid will affect those payments is unclear, but the loss of funding could prompt states to reduce funding to hospitals, which then might be forced to end costly services that don't generate much revenue, such as obstetric care.

"Suffice it to say, there's a lot of questions about what the biggest cut in Medicaid history is going to mean for rural communities and the women who rely on Medicaid there," Burak said, referring to the federal budget cuts. "We already have a maternal health crisis. We already have poor maternal health outcomes. We're already in a situation where women are having to drive longer distances to have babies. What more is going to happen as a result of the new law?"

Because of lost federal dollars, states likely will have to make funding cuts that might affect everyone's health outcomes, not just those of pregnant mothers, Burak pointed out.

"That unfortunately puts a lot more strain on the Catholic social and health service systems already challenged to do everything they can do for their families with limited resources," she said. "It's the entire safety net that's going to be gutted."

New payment and staffing models

Miller said that because of the difficulties in attracting obstetricians to live and work in small rural communities, some small rural hospitals have adopted a model in which physicians with obstetric training who live in a different community come to the rural hospital for a week or more at a time to handle labor and deliveries. The cost of doing this is higher, Miller said, but the model alleviates the challenge of finding specialists who are willing to be full-time employees in the rural community.

A potential solution to ensuring adequate payment for obstetrics care in rural areas, he said, is for insurance companies to adopt a two-part payment model that would offer a "standby capacity payment" designed to cover the fixed costs of maintaining 24/7 obstetric care staffing and fees for individual services designed to cover the additional variable costs incurred when a baby is born. A hospital provides an important service simply by being there and available to deliver a baby, Miller said, and the standby capacity payment would ensure the cost is covered regardless of how many babies are delivered at the hospital in a particular year.

A potential solution to ensuring adequate payment for obstetrics care in rural areas, he said, is for insurance companies to adopt a two-part payment model that would offer a "standby capacity payment" designed to cover the fixed costs of maintaining 24/7 obstetric care staffing and fees for individual services designed to cover the additional variable costs incurred when a baby is born. A hospital provides an important service simply by being there and available to deliver a baby, Miller said, and the standby capacity payment would ensure the cost is covered regardless of how many babies are delivered at the hospital in a particular year.

"It's the same thing in terms of the ED," he said. "It's a good thing that if I don't need emergency care, but I certainly want the ED to be there in case I do. Health insurance plans need to pay hospitals adequately to have emergency physicians and nurses available on a 24/7 basis regardless of how many emergencies there actually are."

Fixes in rural areas

As access to obstetric care tightens, hospital systems are coming up with ways to help expectant mothers in rural areas.

In Southern Illinois, SSM Health is part of the Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative. The collaborative promotes initiatives such as one focused on safe sleep for infants; education on perinatal mental health conditions; and effective communication, collaboration and clinical care during childbirth.

In Louisiana, the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System announced in April that three of its hospitals have earned designations from the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative. To earn the designation, the hospitals had to meet stringent criteria in categories like health equity, evidence-based policies and education, and measurable outcomes.

Avera is using grant funding from the federal Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies Program to increase access to obstetric services and help prevent conditions such as preterm labor and low birth weight. The federal funding allows for remote patient monitoring. A virtual hub of experienced labor nurses can review fetal heart strips or advise nurses at the bedside who don't deliver babies as often.

Berndt calls the hub "a huge resource for our nurses." He has had a few high-risk patients who don't want to travel to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, to see a specialist, so he monitors them while staying in touch with the specialist.

"We hope, or I always believe, that if we can provide obstetrical and general wellness care that's at a high-quality level, that helps our small communities to grow, they don't have to go anywhere else for the care that they need," Berndt said. "Hopefully, down the road, that leads to more patients, stronger communities, better care. But you have to believe in that, because it is a lot of investment to provide rural obstetric care."