BY: MICHAEL R. PANICOLA, Ph.D., and RON HAMEL, Ph.D.

Catholic Health Care Systems Need to Join Others in Adopting Stricter Guidelines

Dr. Panicola is corporate vice president, ethics, SSM Health Care, and Dr. Hamel is senior director, ethics, Catholic Health Association, both in St. Louis.

Physicians have long been committed to promoting the best interests of their patients, ensuring scientific integrity in research, and making treatment decisions free of bias. These are the ethical foundations of the profession. Yet these very foundations are threatened today by the extensive involvement of pharmaceutical, device and other medically related companies (hereafter, "industry") with physicians.1

Currently, industry supports more than half of all continuing medical education,2 sponsors 70 percent of all privately funded clinical research3 and interacts frequently with and provides various financial enticements to physicians. While industry's involvement in health care and with physicians has helped advance medicine and has benefited patients, its ultimate responsibility is to shareholders who expect a return on investment. Much of industry's activity is geared toward this end, including its relationships with physicians.

To be clear, industry-physician relationships not only affect the medical profession but also have far-reaching implications for all those who use and take part in the American health care delivery system. The issue has special relevance for health care organizations insofar as the credibility of such organizations is tied up with the physicians who practice within and/or in the name of these organizations. As such, health care organizations need to be attentive to this issue and act accordingly to curb real or perceived financial conflicts of interest engendered by industry's involvement with physicians. Catholic health care, in particular, should be especially concerned and quick to take corrective action, given its mostly counter-cultural stance vis-à-vis with the market and its commitments to integrity and the common good.

Growing Concern

Until relatively recently, industry-physician relationships were largely unregulated. Physicians were expected to monitor their own behavior and act with integrity for the good of their patients and the profession. Today, however, there is mounting pressure from both within and outside the profession to establish strict guidelines governing industry-physician relationships, especially those with a financial stake. There are two main reasons for this. First, a substantial body of research has emerged in recent years indicating that: (a) industry-supported "education" is often biased and intended primarily to improve product sales; (b) industry-sponsored research lacks objectivity and is often designed in such a way as to yield beneficial results, with negative results downplayed, spun positively or suppressed altogether; and (c) industry's relentless marketing tactics and gifts/payments to physicians unduly influence physicians' behavior and decision making.4 Second, ethical misconduct on the part of drug and device companies as well as physicians has been exposed in recent years, leading to intense media attention, legal settlements totaling billions of dollars, and greater public awareness of financial conflicts of interest. More recent examples include:

- In September 2007, four of the nation's five largest makers of artificial hips and knees agreed to pay $311 million to settle a U.S. Department of Justice investigation into alleged violations of the federal anti-kickback statute. The lawsuit claimed the companies used consulting agreements as inducements for surgeons to use their products.

- In 2008, Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, headed a congressional investigation into financial ties between pharmaceutical companies and academic physicians. The investigation uncovered major financial conflicts of interest for some prominent academic physicians.5

- In January 2009, Eli Lilly & Co. pleaded guilty in federal court of illegally marketing its powerful antipsychotic drug, Zyprexa, for unapproved uses (i.e., depression) and for patients (namely elderly and children) in whom the drug has shown to have serious side-effects. The company set aside $1.4 billion for damages.6

Believing federal oversight is necessary to reduce financial conflicts of interest that arise in relationships between industry and physicians and to promote greater transparency, Sens. Grassley and Herb Kohl, D-Wis., recently introduced a revised version of the Physician Payments Sunshine Act.7 Similar to its predecessor on which the 110th Congress failed to vote, the 2009 version of the proposed law would require industry to disclose on a publicly accessible government website payments to physicians totaling more than $100 annually and would penalize noncompliant companies $10,000 to $100,000 for each infraction with a cap of $1 million per year. Grassley is considering broadening the reporting requirements to include payments made by industry to medical organizations, hospitals, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmacists and pharmacies, continuing medical education groups, and medical schools.

The proposed federal legislation coincides with state laws that set limits on industry gifts/payments to physicians and/or require public disclosure of cash and in-kind payments. States with such laws on the books include Minnesota, California, Maine, Vermont, West Virginia, the District of Columbia and Massachusetts.8 Several other states are currently considering similar laws.

A Look at the Evidence

Despite increasing concern over industry-physician relationships, some question whether legislation is necessary, arguing that industry gifts/payments to physicians are not all that pervasive and not all that lucrative. The research, however, tells a different story. In an oft-cited article published in the New England Journal of Medicine in April 2007, Eric Campbell and colleagues reported on the results of a national physician survey they conducted to assess the nature and extent of industry-physician relationships.9 The authors distributed surveys to 3,167 physicians in six specialties (anesthesiology, cardiology, family practice, general surgery, internal medicine, and pediatrics) practicing in diverse settings and received a raw response rate of 52 percent. The survey included nearly 50 questions, with one asking "Which of the following have you received in the last year from drug, device, or other medically related companies?" Among the potential responses: Food or beverages in workplace; drug samples; honoraria for speaking; payment for consulting; payment for service on advisory board; payment in excess of costs for enrolling patients in industry-sponsored trials; costs of travel, time, meals, lodging or other personal expenses for attending meetings; gifts received as a result of prescribing practices; free tickets to cultural or sporting events; and free or subsidized admission to meetings or conferences for continuing medical education.

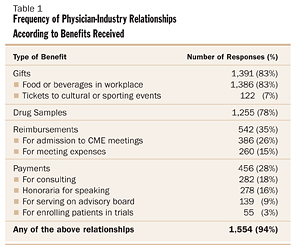

Astonishingly, 94 percent of the physicians who responded stated that they had received at least one of the items listed above, with 83 percent indicating they received some sort of gift, and 78 percent stating they had received free drug samples. (See Table 1)

Campbell and colleagues also looked into the frequency of interactions between physicians and pharmaceutical representatives and reported from the surveys returned that representatives met with family practitioners on average 16 times per month, internists 10 times per month, cardiologists nine times per month, pediatricians eight times per month, surgeons four times per month and anesthesiologists two times per month. This is not all that surprising given that there are about 90,000 pharmaceutical representatives to meet with the roughly 567,000 American physicians (or one representative for every 6.3 physicians).

What the article by Campbell and colleagues does not tell us is just how much money in the form of gifts and payments physicians receive from industry. This is more difficult to ascertain given the lack of transparency and public disclosure. Nevertheless, data compiled by IMS Health, which monitors industry's finances, give us a glimpse into some of the spending by industry to physicians. In 2004, for instance, the pharmaceutical industry spent on average $10,000 per practicing American physician on free meals, free continuing medical education training, free trips to conferences, and payments for various services (e.g., consulting and speaking). Pharmaceutical companies also gave the average U.S. physician $21,000 in free drug samples, which, when you include the above figures, totals $23.7 billion for 2004 — twice as much money as was spent just six years earlier.10

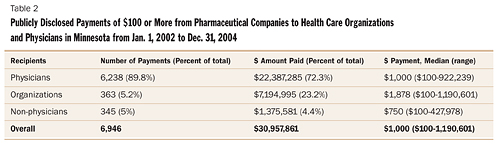

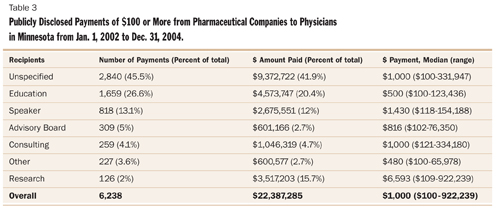

State disclosure data on industry gifts/payments to physicians also shed some light on this now ubiquitous practice. Joseph Ross and colleagues reported in the March 2007 issue of Journal of the American Medical Association on their efforts to assess the prevalence and magnitude of disclosed payments of $100 or more from industry to physicians in Vermont and Minnesota.11 Looking at the Minnesota data, which are particularly helpful because the law makes all disclosed data part of the public record, Ross and colleagues found that from Jan. 1, 2002, through Dec. 31, 2004, pharmaceutical companies issued 6,238 payments of $100 or more to Minnesota physicians totaling more than $22 million, with payments ranging from $100 to $922,239 (see Table 2). The majority of these payments were for an unspecified purpose (2,840, or 45.5 percent), followed by payments for education (1,659, or 26.6 percent), speaker honoraria (818, or 13.1 percent) and service on an advisory board (309, or 5 percent) [see Table 3].

While the numbers may seem staggering, Ross and colleagues caution that their study is limited to only two states with a relatively small number of physicians. What is more, the total number and value of payments for physicians in these two states are most likely significantly underestimated because of the lack of quality of the obtainable data. Ross and colleagues note, "Our analysis was limited by the quality of the obtainable data, which were variously nonstandardized, inconsistently reported, or withheld on trade secret grounds."12 Beyond this, Ross and colleagues reveal that estimates account only for payments publicly disclosed and those of $100 or more (in Vermont, for instance, 77 percent of all payments were for less than $100) and do not include payments related to samples, publications and educational materials, which account for a substantial portion of the total dollars spent by pharmaceutical companies to market their products to physicians.13

So, based on what we know through surveys, studies and publicly reportable data, physicians have extensive ties with industry and, all things considered, receive a substantial amount of money from industry. Yet, interestingly, in survey after survey most physicians insist that industry gifts/payments do not unduly influence their judgment.14 But, again, the research suggests otherwise. Older and more recent studies suggest gifts/payments create conflicts of interest that unconsciously bias physicians and lead to inappropriate use and over-utilization of medical devices and drugs, reduced generic prescribing, increased overall prescription rates and thereby increased expenditures on prescription drugs,15 formulary requests for drugs with few or no advantages over existing drugs, and quick uptake of the newest, most expensive devices and drugs, including those of only marginal benefit over existing options with established safety records.16

Of the more recent studies, Ashley Wazana reviewed 29 empirical studies that provided data on gifts/payments to physicians by industry. She concluded that meetings with pharmaceutical representatives were associated with requests by physicians for adding the drugs to the hospital formulary and changes in prescribing practice; attending sponsored continuing medical educational events and accepting funding for travel or lodging for educational symposia were associated with increased prescription rates of the sponsor's medication; and attending presentations given by pharmaceutical representative speakers was associated with what she describes as "non-rational prescribing."17

Likewise, Troyen Brennan and colleagues examined the nature and extent of industry-physician relationships that create conflicts of interest in light of emerging research in diverse fields and concluded the following: data show financial enticements by industry create a strong impulse to reciprocate on the part of physicians and unduly influence their behavior; the rate of drug prescriptions by physicians increases substantially after they see sales representatives, attend company supported symposia, or accept samples; and physicians who request additions to hospital drug formularies are far more likely to have accepted free meals or travel funds from drug manufacturers. Given this, Brennan and colleagues argue that all gifts/payments should be prohibited; samples should be banned and replaced by a voucher system for low-income patients; physicians with financial ties to industry should be excluded from formulary committees; industry support for continuing medical education should flow through a central repository; funds for physician travel to conferences should be handled by a central office; physicians' participation on speaker's bureaus and ghost-writing should be banned; and consulting and honoraria should always be tied to a contract with explicit tasks and payments commensurate to the tasks assigned.18

In one of the more fascinating studies on the subject, Jason Dana and George Loewenstein applied social science research on conflicts of interest to the issue of gifts to physicians from industry and concluded that data show gifts and payments to physicians have an unconscious influence and create a strong feeling of reciprocity. This is why physicians often say they are not unduly influenced by relationships with and enticements from industry. Research, however, suggests otherwise. From this the researchers suggest that because bias induced by monetary interests is unconscious and unintentional, there is little hope of controlling it by limiting gift size, engaging in educational initiatives, or mandating disclosure. Rather, the simple and most effective solution is to prohibit gifts and payments altogether.19

Winds of Change

Cumulatively, all the scandals, lawsuits and studies point to the need to create greater distance between those who make medical goods for a profit and those who determine the safety and efficacy of those goods and use them to care for patients. Recognizing as much, several influential health care groups have recommended or revised existing guidelines governing industry-physician relationships. Some are more permissive, relying primarily on physician judgment and discretion, such as those of the American Medical Association20 and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.21 Others, however, are more restrictive, placing strict limits on certain interactions or exchanges, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, the Institute on Medicine as a Profession,22 the Association of American Medical Colleges,23 and the Institute of Medicine as reflected in its April 28, 2009, report titled "Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice."24

Health care organizations, too, are trying to get ahead of proposed federal legislation by requiring associated physicians to reveal their financial ties with industry on the organizations' websites. For instance, the Cleveland Clinic now requires disclosure of physicians and researchers' financial ties to industry and makes this information available on its website, www.clevelandclinic.org, under each of its physicians' particular web pages. Park Nicollet Health Services recently became the first health care system in Minnesota to require its physicians to disclose publicly their financial relationships with drug and device companies.

Seeing the writing on the wall or perhaps just reacting to the inevitable, industry itself has tightened its own standards or guidelines. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, which represents the country's leading pharmaceutical research and biotechnology companies, recently revised its voluntary "Code on Interactions with Healthcare Professionals." The organization's revised code, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2009, includes the following:

- Prohibits distribution of non-educational items (such as pens, mugs and other "reminder" objects typically adorned with a company or product logo) to health care professionals and their staff, but permits educational items of less than $100.

- Prohibits company sales representatives from providing restaurant meals to health care professionals, but allows them to provide occasional meals in office or hospital settings in conjunction with informational presentations.

- Prohibits the provision of any entertainment or recreational benefits to health care professionals, such as tickets to sporting events and vacation trips.

- Permits reasonable compensation to health care professionals for speaking and consulting arrangements, but suggests appropriate disclosure regarding the existence and nature of the relationship with the company.25

Likewise, the Advanced Medical Technology Association, which is the largest member association in the United States for manufacturers that produce medical devices, diagnostic products and health information systems, recently revised its voluntary "Code of Ethics on Interactions with Health Care Professionals," incorporating similar standards. The association's revised code goes into effect July 1, 2009.26

An Opportunity for Catholic Health Care

As a major provider in the American health care system, Catholic health care has an opportunity to align itself with the academic medical centers and private health care systems that already have set tough standards concerning industry-physician relationships. Doing so follows inexorably from Catholic health care's overall mission and the values out of which it operates, especially human dignity, justice, stewardship and the common good. Demonstrating leadership in this area is ultimately a matter of identity and integrity for Catholic health care.

Part III of the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services speaks to the nature of the health professional-patient relationship which is viewed as "never separated from the Catholic identity of the health care institution."27 This suggests that, at minimum, the relationship ought not be contrary to the values that mark Catholic identity. Preferably, it should be shaped by them. The introduction to the directives further states that the health professional-patient relationship ought to be characterized, in part, by "mutual respect, trust, [and] honesty" and be grounded in respect for the dignity of the human person. "When the health care professional and the patient use institutional Catholic health care, they also accept its public commitment to the Church's understanding of and witness to the dignity of the human person."28 Obviously, current practices within industry-physician relationships can weaken or even undermine honesty and trust, and can be harmful to patients physically, emotionally and economically. They promote neither the best interests of the patient nor respect for human dignity. Such practices are at variance with the foundations of the physician-patient relationship as well as one of the grounding commitments of Catholic health care.

Reform of industry-physician relationships is critical to the integrity of the physician-patient relationship as well as to the well-being of patients and health care organizations. Current practices weaken trust in physician decisions about medical devices and drugs, needlessly and perversely increase costs, may well detract from institutional efforts at improving quality and striving for excellence, and could contribute to patient dissatisfaction and, ultimately, harm the reputation of the organization. Justice and good stewardship would seem to require the elimination of financial conflicts of interest.

Finally, Catholic health care's commitment to contributing to the common good would suggest that it assume a leadership role in the matter of industry-physician relationships. The practices that have developed over the years between industry and physicians can hardly be said to contribute to the common good of society. Rather, they are structures that perpetuate lack of transparency, bias, injustice and inflated costs. They directly contribute to our broken health care system.

There are many ways Catholic health care organizations can approach the issue of industry-physician relationships. SSM Health Care, headquartered in St. Louis, for instance, recently established a task force comprised of select physicians from all of its markets as well as specific professionals in the areas of ethics, corporate compliance and supply chain management. The task force, which is chaired by a physician, is charged with evaluating and revising the organization's current policy governing industry-physician relationships as it relates to the provision of gifts, payments, reimbursements and drug/device samples; industry-sponsored education, industry support for scholarships, fellowships or other support for students, residents and trainees; and facility access for industry representatives. The task force was given a specific deadline of May 31, 2009, to offer its recommendations, which will then be incorporated into a new policy scheduled to become effective July 1, 2009. At present, it is unclear what the organization's policy will ultimately look like. There is, however, unanimous agreement that more restrictive guidelines governing industry-physician relationships are necessary if SSM Health Care is going to fulfill its mission and live out its values, particularly stewardship, community and excellence.

It is the hope of the authors that those Catholic health care systems that have not revised their industry-physician policies will do so soon in order to create greater distance between industry representatives and physicians so that financial conflicts of interest can be eliminated or at least significantly reduced.

NOTES

- Troyen A. Brennan et al., "Health Industry Practices that Create Conflicts of Interest: A Policy Proposal for Academic Medical Centers," Journal of the American Medical Association 295 (Jan. 25, 2006): 429-433.

- Arnold S. Relman, "Industry Support of Medical Education," Journal of the American Medical Association 300 (Sept. 3, 2008): 1071-1073, at 1071.

- ACOG Committee on Ethics, Opinion, "Relationships with Industry," Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 401 (March 2008): 799-804, at 800.

- Marcia Angell, "Industry-Sponsored Clinical Research: A Broken System," Journal of the American Medical Association 300 (Sept. 3, 2008): 1069-71; also see her article, "Drug Companies and Doctors: A Story of Corruption," New York Times Review of Books 56, Jan. 15, 2009.

- See Angell, "Drug Companies and Doctors: A Story of Corruption." Some of the names mentioned in the article include: a) Dr. Joseph Biederman, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and chief of pediatric psychopharmacology at Harvard's Mass General, noted as the most prominent researcher and physician promoting the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder, who was found to have received $1.6 million in consulting and speaking fees between 2000 and 2007 from drug companies, including those that make drugs he advocates for off-label use for the treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder; b) Dr. Alan Schatzberg, chairman of Stanford's psychiatry department and president-elect of the American Psychiatric Association, who was found to control more than $6 million of stock in Concept Therapeutics, a company he co-founded, which is testing mifepristone (RU 486) as a treatment for psychotic depression, though, he was serving as principal investigator in a National Institute of Mental Health grant that included research on the drug for this use and he co-authored three papers on the subject; and c) Dr. Charles Nemeroff, chairman of Emory University's department of psychiatry, principal investigator on a five-year, $3.95 million National Institute of Mental Health grant to study several drugs made by GlaxoSmithKline, who failed to disclose about $500,000 he received from GlaxoSmithKline for giving dozens of talks promoting the company's drugs and, in 2004, lied by stating he received only $9,999 when in fact he received $171,031 from the company.

- This is not the first infraction for Lilly with Zyprexa. In 2005, the company agreed to pay $700 million to settle 8,000 suits and, in 2007, agreed to pay $500 million to settle 18,000 suits from people who claimed they were harmed by the drug.

- Physician Payments Sunshine Act of 2009, proposed Senate bill 301 for the first session of the 111th Congress. Review the bill online at www.opencongress.org.

- For a succinct review of state laws governing industry-physician relationships, see The Prescription Project, "Regulating Industry Payments to Physicians: Identifying and Minimizing Conflicts of Interest," Sept. 12, 2008, at www.prescriptionproject.org/tools/solutions_factsheets/files/0006.pdf.

- Eric Campbell et al., "A National Survey of Physician Industry Relationships," New England Journal of Medicine 356 (April 26, 2007): 1742-1750.

- John Dudley Miller, "Study Affirms Pharma's Influence on Physicians," Journal of the National Cancer Institute 99 (Aug. 1, 2007): 1148-1150, at 1148.

- Joseph S. Ross et al., "Pharmaceutical Company Payments to Physicians: Early Experiences with Disclosure Laws in Vermont and Minnesota," Journal of the American Medical Association 297 (March 21, 2007): 1216-1223.

- Ross et al., 1222.

- Ross et al.

- See, for instance, L. Lewis Wall and Douglas Brown, "The High Cost of Free Lunch," Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 110 (July 2007): 169-173. Also see M.A. Morgan et al., "Interactions of Doctors with the Pharmaceutical Industry," Journal of Medical Ethics 32 (October 2006): 559-563; and Susan Chimonas, Troyen Brennan and David Rothman, "Physicians and Drug Representatives: Exploring the Dynamics of the Relationship," Journal of General Internal Medicine 22 (February 2007): 184-190.

- Retail spending on prescriptions has increased rapidly, more than doubling from $64.7 billion to $202 billion between 1995 and 2007 with an estimated one-quarter of this increase resulting from a shift to the prescribing of more expensive drugs. For more information on total retail sales rank ordered by state, go online to the Kaiser Family Foundation's website at www.statehealthfacts.org.

- For some of the more notable older studies, see among others: Jerry Avorn et al., "Scientific Versus Commercial Sources of Influence on the Prescribing Behavior of Physicians," American Journal of Medicine 73 (July 1982): 4-8; Lurie et al., "Pharmaceutical Representatives in Academic Medical Centers: Interaction with Faculty and Housestaff," Journal of General Internal Medicine 5 (May-June 1990): 240-243; James Orlowski and Leon Wateska, "The Effects of Pharmaceutical Firm Enticements on Physician Prescribing Patterns," Chest 102 (July 1992): 270-273; Joel Lexchin, "Interactions Between Physicians and the Pharmaceutical Industry: What Does the Literature Say?" Canadian Medical Association Journal 149 (Nov. 15, 1993): 1401-1406; and T.S. Caudill et al., "Physicians, Pharmaceutical Sales Representatives, and the Cost of Prescribing," Archives of Family Medicine 5 (April 1996): 201-206.

- Ashley Wazana, "Physicians and the Pharmaceutical Industry: Is a Gift Ever Just a Gift?" Journal of the American Medical Association 283 (Jan. 19, 2000): 373-380.

- Brennan et al., 429-433.

- Jason Dana and George Loewenstein, "A Social Science Perspective on Gifts to Physicians From Industry," Journal of the American Medical Association 290 (July 9, 2003): 252-255.

- American Medical Association, Code of Medical Ethics, Opinion E-8.061, "Gifts to Physicians from Industry," March 2008. Available online at www.ama-assn.org.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee on Ethics, Opinion, "Relationships with Industry," 799-804. Available online at www.acog.org.

- American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and the Institute on Medicine as a Profession, Task Force, January 2006.

- Association of American Medical Colleges, Task Force, April 2008.

- To review the report and to find information on purchasing it, visit the Institute of Medicine's website at www.iom.edu.

- Review the organization's code online at www.phrma.org.

- Review the association's code online at www.advamed.org.

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, (Washington, D.C.: USCCB, Fourth Edition, 2001), 18.

- USCCB, 17-18.

Copyright © 2009 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.