BY: DAVID LEWELLEN

In the first week of the coronavirus epidemic in the Bay Area, Sr. Donna Moses, OP, a chaplain, was asked to visit a dying patient who was symptomatic for COVID-19. At the nurses' recommendation, she put on an N95 mask, a gown, a face shield and two sets of gloves.

She prayed with the patient, who "appeared to derive some peace from it, but I was no image of peace wearing that gear," said Sr. Moses, the spiritual services coordinator at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, California. Chaplains "do a lot by eye contact and a calm voice, and that's all impeded – even your voice doesn't sound the same through the mask. I was thinking, gosh, that's not the last image anyone would want to see on earth."

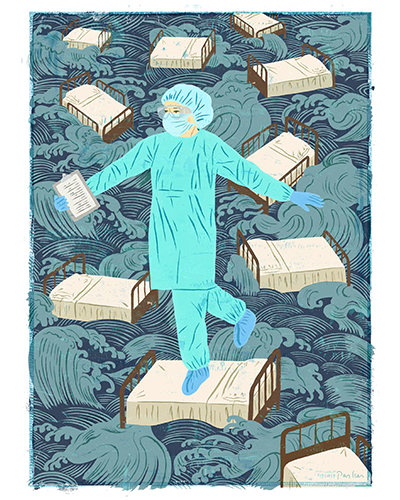

As the coronavirus upends normal health care delivery, chaplains and spiritual care departments also find that everything has changed. Simply visiting with patients and families presents formidable new challenges, and feelings of fear are compounded by loneliness and isolation. Like every other hospital department, spiritual care is figuring out solutions on a daily basis.

Immediate Need with Concern about the Toll

"This is a mass disaster of epic proportions," said Tim Serban, the system disaster response officer for Providence St. Joseph Health in Portland, Oregon. Disaster responders know that huge adverse events first have heroic and honeymoon phases, in which the community rallies and comes together, followed by the disillusionment phase. When that begins is "anyone's guess at this point," Serban said. "There are multiple ground zeroes," he said, broadly referring to locations in this pandemic that have experienced crisis-level caseloads. During the first week of April, the United States had more than 360,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and nearly 11,000 deaths. Worldwide, 79,000 deaths total had been recorded by that point, according to information from the Johns Hopkins coronavirus resource center.

If health care workers and ordinary citizens don't know how long they have to be in a state of constant readiness, "that requires a pacing of how to help people find their `groundedness.' We may not have clarity about when it ends," Serban said.

But trying to put catharsis on hold is "like holding a beach ball underwater," said Serban, who is also the regional spiritual officer for Providence St. Joseph. Due to social distancing practices to keep the virus from spreading, hospitals and long-term care facilities have eliminated or severely restricted visitors. Large funerals cannot be held currently for those who die. "Families are being asked to hold that grief down until they can have a ritual to say goodbye."

Sr. Moses has observed staffers already showing signs of physical and mental exhaustion, with no idea of when the situation will end. In debriefing with staff after wearing the full protective gear, she found that "the nurses have the same feeling: 'Am I comforting this person? Am I exposed? Can we contaminate each other?'"

Rapid Increase in Telechaplaincy

For the moment, the human connection available to chaplains is largely electronic. For years, telechaplaincy has been an intriguing possibility, but the current pandemic has dramatically stepped up its use. "We're given very little option in this time," said Austine Duru, vice president of mission for Mercy Health in Youngstown, Ohio. "It becomes necessary, and we are forced to be creative. We can connect in new ways that are not very traditional."

In the absence of families in the waiting room or patient's room, Duru's staff has begun making phone calls to their relatives. "It's shifted the dynamic. We've had very good success and a lot of positive feedback."

Figuring out telechaplaincy on the fly is like "learning to breathe underwater," said Nicholas Perkins, a chaplain at Franciscan Health Dyer in Indiana. With no loved ones clustered around the bedside, "it's a dual isolation, for the patient as much as the family," Perkins said. "That's a source of great pain and sadness." And when chaplains talk with families, "you can't see their body language, you can't offer a box of Kleenex, you can't put your arm on their shoulder. That's the brand-new layer to all of this."

Perkins lost three patients to COVID-19 in a recent weekend. While patients are still living, he has been praying from the doorway. But after death, he dons the full protective suit, enters the room, and, "I have a sacred moment of prayer over the deceased, along with those who tended the deceased, asking for resilience, fortitude and strength." An hour or two later, after the doctors have broken the news to the family, he calls them to check in, console, pray, talk about funeral arrangements, and "let them know that even though it's a phone call, I'm with them."

Frequent Check-ins, Moving Forward

In coming months, Serban said, health care workers may well face "battlefield-like PTSD, like what the military faces in wartime. It could be a mass psychological casualty event." When health care workers take a 10-minute shift break, they, or chaplains, can do a quick psychological first-aid assessment: "Focus on the breath, on the moment, on the ways you can cope. Don't tap into what you've seen or heard. Are you safe? Is your family safe? Have you been hydrating?"

And in the midst of the chaos and the grief, Serban is thinking about hope. "Have confidence in the fact that together we can overcome. We know from history. We are all survivors of all pandemics. How can we remain calm and helpful, and how can we keep each other safe?"

DAVID LEWELLEN is a freelance writer in Glendale, Wisconsin, and editor of Vision, the newsletter of the National Association of Catholic Chaplains.