CEDAR RAPIDS, Iowa — When Bob Kazimour and his wife, Jan, were honorary chairs of a fundraising effort about a decade ago to raise capital to start the Family Caregivers Center on the Mercy Medical Center campus in Cedar Rapids, little did he know that center would become a vital resource for him.

When Jan developed Alzheimer's years later and in time became nonmobile and nonverbal, he found his caregiving role to be increasingly difficult. He turned to the Family Caregivers Center and got access to a wide range of resources and joined a men's coffee group. Those men who are caregivers to spouses with dementia have been meeting since 2016 to talk about what they are experiencing and to share insights on how to better care for themselves and their wives.

"This group has been wonderful for me — we've helped each other a lot," Kazimour says. With the support of the other men in the group, "I don't feel like a lone ranger," he says. Kazimour's wife died Sept. 7.

Kazimour is among the thousands of Cedar Rapids-area caregivers who have received resources, services, programming and support from the Family Caregivers Center since its 2015 opening. According to founder and Director Kathy Good, the center seeks to ease caregivers' stress and equip them to nurture themselves and their loved ones.

Around-the-clock role

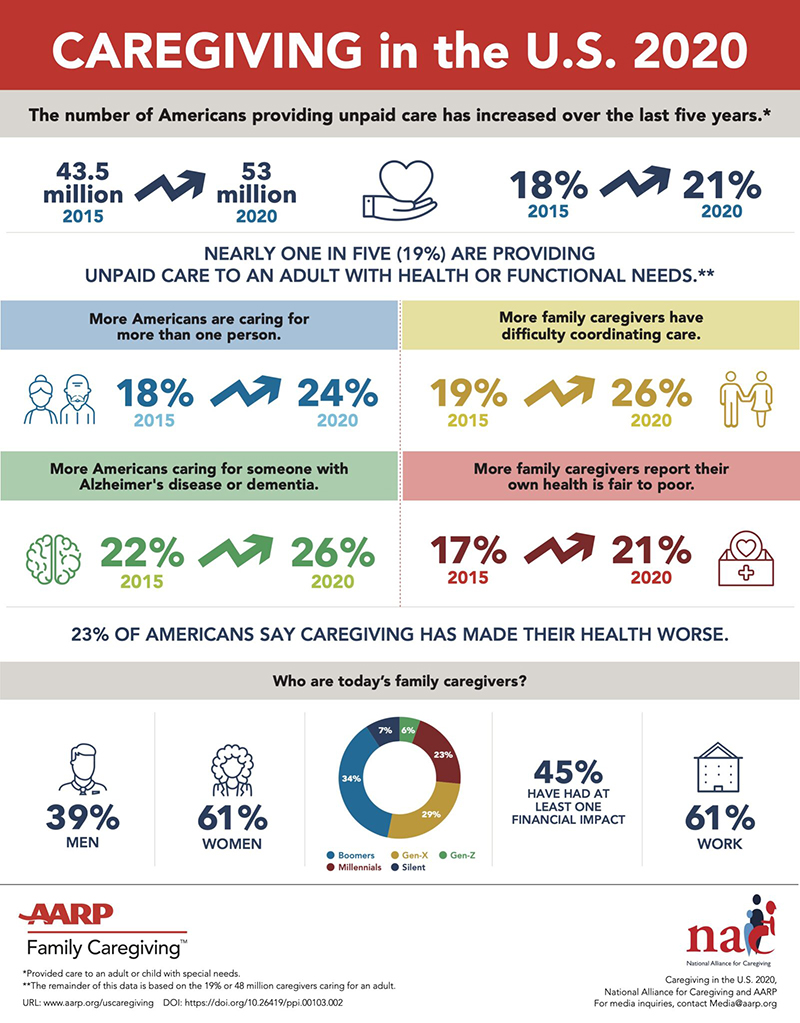

A 2020 report from the National Alliance for Caregiving says about 53 million people in the U.S. are unpaid caregivers.

This role can be highly stressful and emotionally and physically taxing; and for some it is a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week role. It can be so strenuous and difficult that the caregivers themselves can pay a price in terms of their own mental and physical well-being. An estimated 40% of caregivers die before the person they are tending to. Mary Ann Grobstich, a community facilitator with the Family Caregivers Center, says these caregivers are at great risk, especially since in many communities there is not much support available.

To address such gaps that were evident in Cedar Rapids a decade ago, Good accepted the challenge of Tim Charles, who was Mercy Cedar Rapids president and CEO at the time, to see whether Mercy could replicate the idea of a family caregiver center he'd seen in New York. Good, who had a social work background, was an acquaintance of Charles. At the time he approached her, she was a caregiver for her husband, Dave, who had Alzheimer's and was a resident of Mercy's HallMar care center.

From concept to reality

Good embarked on an extensive effort to create a center that would aid caregivers and the people they were supporting. She worked with Mercy leadership and a committee of community leaders with caregiving

experience to study the gaps in services for caregivers locally, consult numerous caregivers and experts in caregiving, build plans for the center, fundraise for it and coordinate its development and eventual completion.

The Family Caregivers Center opened on the Mercy campus in 2015. Mercy since has opened another center in suburban Cedar Rapids — Chris & Suzy DeWolf Family Innovation Center for Aging & Dementia — to spur innovation in programming for people living with chronic conditions including changing cognitive abilities.

The two centers share a staff of less than a dozen, with most of them having a social work background and many of them with lived experience as caregivers. Dozens of volunteers support the centers' work. The Family Caregivers Center has an annual budget of about $450,000, and the Innovation Center, about $400,000 (excluding the Center for Memory Health that is on the premises). Since partnering recently, Mercy Cedar Rapids and Presbyterian Homes & Services jointly own the buildings. The centers are funded by Mercy and through philanthropy.

Ever-growing list of offerings

Good, her team, volunteers and a committee of community members with caregiving experience are continually evolving and expanding the resources that the Family Caregivers Center and the Innovation Center

provide. Many of the centers' offerings are free, though clinical services provided at the Center for Memory Health at the Innovation Center are paid by insurance.

Caregiver resources currently are available at both the Family Caregivers Center and the Innovation Center. Staff meet one-on-one with every family who seeks services and talk to them about their situation and needs then connect them with services. The centers' staff — in many cases along with trained volunteers — offer emotional support; help accessing community resources, respite services, educational presentations, and referrals to legal services such as on wills and advance directives. The centers have a lending library of materials that offer caregivers relevant information. The centers are getting ready to debut an online networking tool for caregivers.

But the bread and butter of the centers' caregiver offerings are the numerous support and social groups that caregivers can access. Many are available as hybrid in-person and virtual gatherings. There are groups available for women caregivers, men caregivers, couples in which one person is living with dementia, and people transitioning out of caregiving after their loved one's death. There are exercise, gardening, journaling and spirituality workshops, all geared to caregivers. Sometimes the workshops are open to people living with chronic conditions. There also are group series on the legal aspects of caregiving, sexuality between caregivers and their spouses with dementia, and loss and grieving. More groups and sessions are being added continually.

The centers offer companions for people with dementia while spouses attend sessions.

Hunger for services

Sue Rowbotham is a volunteer who co-facilitates a support group for people with early-stage dementia. She says "people are hungry for" what the centers are providing. Some people participate in multiple support

groups and classes and also sign on as volunteers.

Staff member Grobstich says a key reason people choose to become so invested and involved in the centers has to do with the culture the centers have created. She says the focus is on building trusting relationships and on engagement. "We have this commonness in caregiving, and that is humbling," Grobstich says. "This creates an openness to learn and to have real connections with one another."

Kathy Krapfl, the Family Caregivers Center office coordinator, says, "You can see the relief of caregivers when they are in the groups, when they are in the network (of caregivers). They find joy. There is laughter."

It is usual for caregivers in the support groups and other activities to build deep and lasting friendships with one another. They commonly socialize outside of classes and sessions.

Lisa Hawk, a center social worker and counselor, says in this environment, "caregivers feel safe to process what they are going through. They feel they have permission to focus on their own needs," which can be very difficult for them to do.

The centers have found that meeting the multidimensional needs of caregivers can greatly enhance the caregivers' health and well-being, which can in turn improve mental health and clinical outcomes. This can be true for both the caregivers and those they are caring for.

"It takes a whole team to ensure caregivers are healthy and well," says Abby Weirather, manager of the Family Caregivers Center.

Hawk adds: "Caregiving is never going to be easy, but we are trying to make it easier."