In her 20 years in pediatrics, Dr. Lara Johnson had never treated a child with measles. That is, not until late January, when Covenant Children's in Lubbock, Texas, where she is a hospitalist, started to admit patients with severe cases.

One of those patients, a school-aged child, died of complications of measles on Feb. 26. As of March 6, the hospital had admitted about three dozen children who needed acute care because of the virus.

Johnson, who is chief medical officer for the Covenant Health Lubbock service area, said the children's hospital is preparing for many more. "I don't know how long it will last, but based on some other outbreaks that have been studied and reported on, we're probably maybe not yet halfway finished," Johnson said.

The Texas Department of Health had tallied 198 cases in the outbreak by March 7. The death at Covenant Children's was the only fatal case at that time.

Johnson said the death of the patient with a vaccine-preventable illness was emotional for the staff. "The whole hospital really came together to support everyone through that time as we would, as we do, anytime we have a sad outcome," she said.

Care for a vast region

Covenant Children's is the only strictly pediatric hospital for a vast region that spans northwest Texas and neighboring states. The hospital is part of Covenant Health, a subsystem of Providence St. Joseph Health.

Johnson said Covenant Children's began preparing for a potential outbreak when confirmed cases of measles began popping up in Texas. The state health department issued its first release about two confirmed cases on Jan. 23. Those cases were in Houston, 500 miles from Lubbock. On Jan. 30, the department announced two more confirmed cases, this time in Gaines County, part of Covenant Children's service area. That county has since had the most cases – 137 as of March 7.

When its first measles patients were admitted in those final days of January, Johnson said, Covenant Children's was at the ready:

- The infectious disease experts had established protocols to keep the virus from spreading within the hospital.

- The physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists had been briefed on how to care for patients with severe measles cases, which can cause dehydration, difficulty breathing, and seizures, among other symptoms.

- The facilities team had set up negative pressure rooms to isolate the patients with measles.

- The supply chain team had a cache of protective equipment such as N95 face masks on hand for care providers.

- The environmental services team was trained on proper cleaning procedures for areas where patients with the highly contagious virus were treated.

- The pharmacy department had stocked a supply of measles-related medications, such as prophylaxis that can reduce the risk of contracting the virus after exposure.

- The communications staff had processes in place to keep staff and the public informed on the hospital's response.

"It was a whole hospital, whole system effort to kind of get up and running," Johnson said.

To oversee all the pieces of the response, Covenant Children's quickly set up an incident command center that will remain in place until the outbreak ends.

The hospital isn't alone in its battle. Johnson praised the collaborative efforts of local and state public health officials, including in assisting in contact tracing to pinpoint the sources of the spread, informing the public of the risk and setting up vaccination clinics.

"I think all of that has been working the way that you want it to," Johnson said.

Vaccine hesitancy

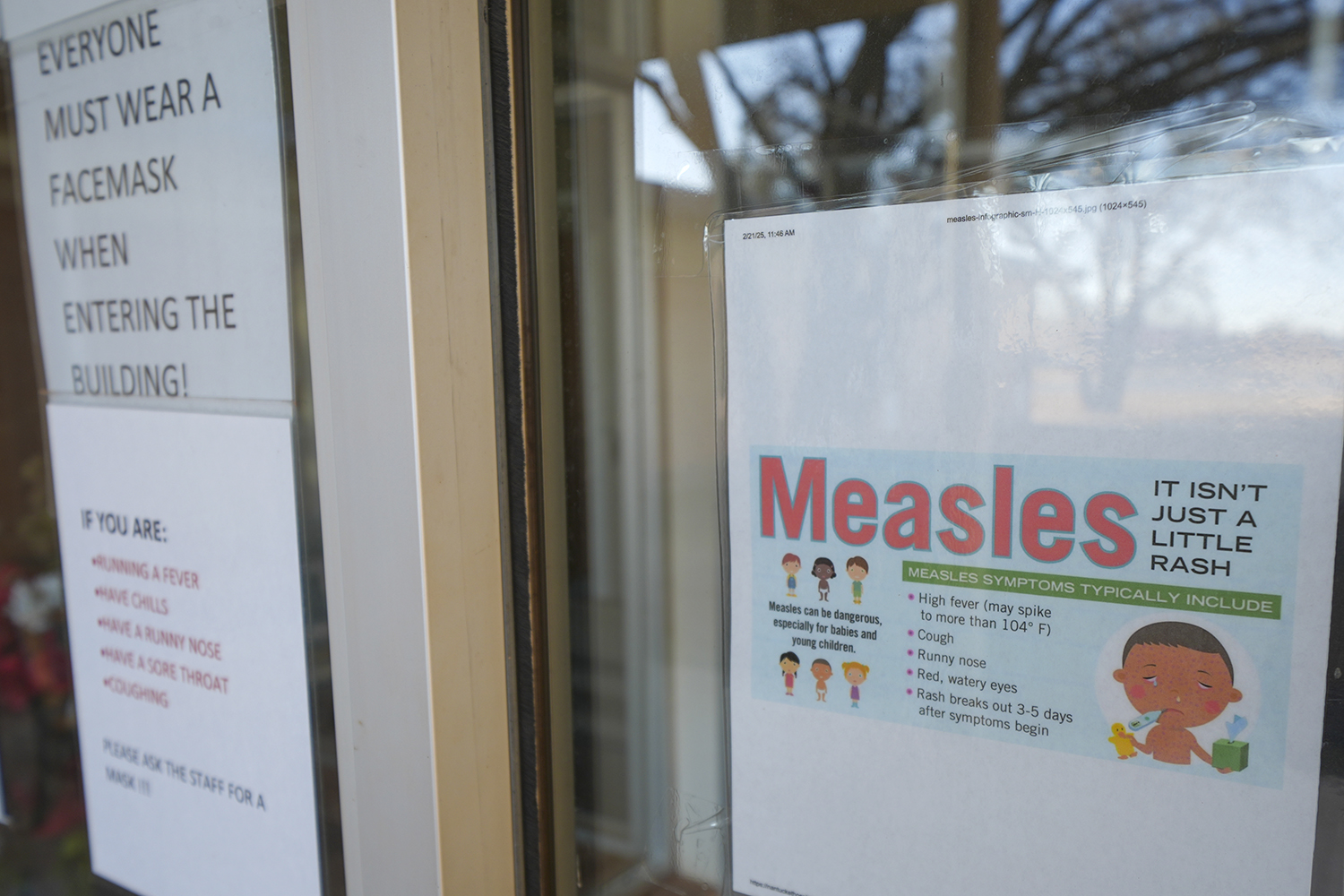

Unvaccinated people have about a 90% chance of contracting measles if they are in a room with someone who has the virus, Johnson noted. Because measles has a typical incubation period of about seven days, people who get immunized within 72 hours of exposure reduce their risk of contagion.

Health officials have stressed that vaccine hesitancy is at the heart of the Texas outbreak. The outbreak began in a population with low vaccination rates. Of the about three dozen patients with measles who have been hospitalized at Covenant Children's, none have been vaccinated.

In 1962, the year before the measles vaccine was licensed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there were almost 500,000 cases. In 2020, there were 13 cases. The number jumped to 285 last year and this year it is on track to surpass that.

Johnson thinks the reason for the uptick in cases of measles and other diseases that can be prevented with vaccines might be that the medical sector is a victim of its own success. "As these vaccine-preventable illnesses kind of fade from our common memory, I think it maybe changes how people think about them," she said. "People may think about them as something from the past."

She noted that an outbreak "may just help bring into focus that these illnesses are only preventable if we have a high rate of vaccination."

Staying focused

Johnson has given several media interviews since the start of the measles outbreak. She talks up the need for and importance of vaccination and for people who don't want to be vaccinated to take precautions to avoid infection. She said she's not trying to use the crisis in Texas as a cautionary tale or wade into the contentious debate over vaccines.

"I think the intention is not to talk about anything controversial ever as a physician," Johnson said. "My intention is just to talk about the things that are true, and to provide information and to answer questions. From my perspective, that's what I've been trying to do."

She added that she is avoiding social media, where conspiracy theories about vaccinations and the source of the Texas outbreak flourish, and she advises her colleagues to do the same.

"It's important to keep our focus on the patients that we serve and on our mission," she said. "We're here to care for the poor and vulnerable, and we're here to provide care to our community and be a resource to our community."