Rev. Diane Smith knows the hospice education program she leads for predominantly Black churches resonates with those who enroll.

She recalls the time a man popped into a virtual class as he was riding in a car. He told Rev. Smith: "My sister died. We went down south to a funeral. I'm on my way back, but I didn't want to miss this session."

Another woman tuned in to the training while hospitalized. "I said, 'Are you sure you want to be on this call?'" Rev. Smith asked her. "She says, 'Oh, yes, I'm going to get my certificate.'"

Rev. Smith directs The African American Church Empowerment Project at Livonia, Michigan-based Angela Hospice and gives certificates those who complete the training. She is also the hospice's director of ministry engagement and chief diversity officer.

The Empowerment Project isn't about promoting Angela Hospice's services, Rev. Smith explains, but rather about educating the community on hospice care and listening to concerns about end-of-life issues.

"It is such a wonderful experience for those of us who facilitate the trainings, because people want the information and they want to have a safe place to even talk about their own experiences," she says.

Conversation to project

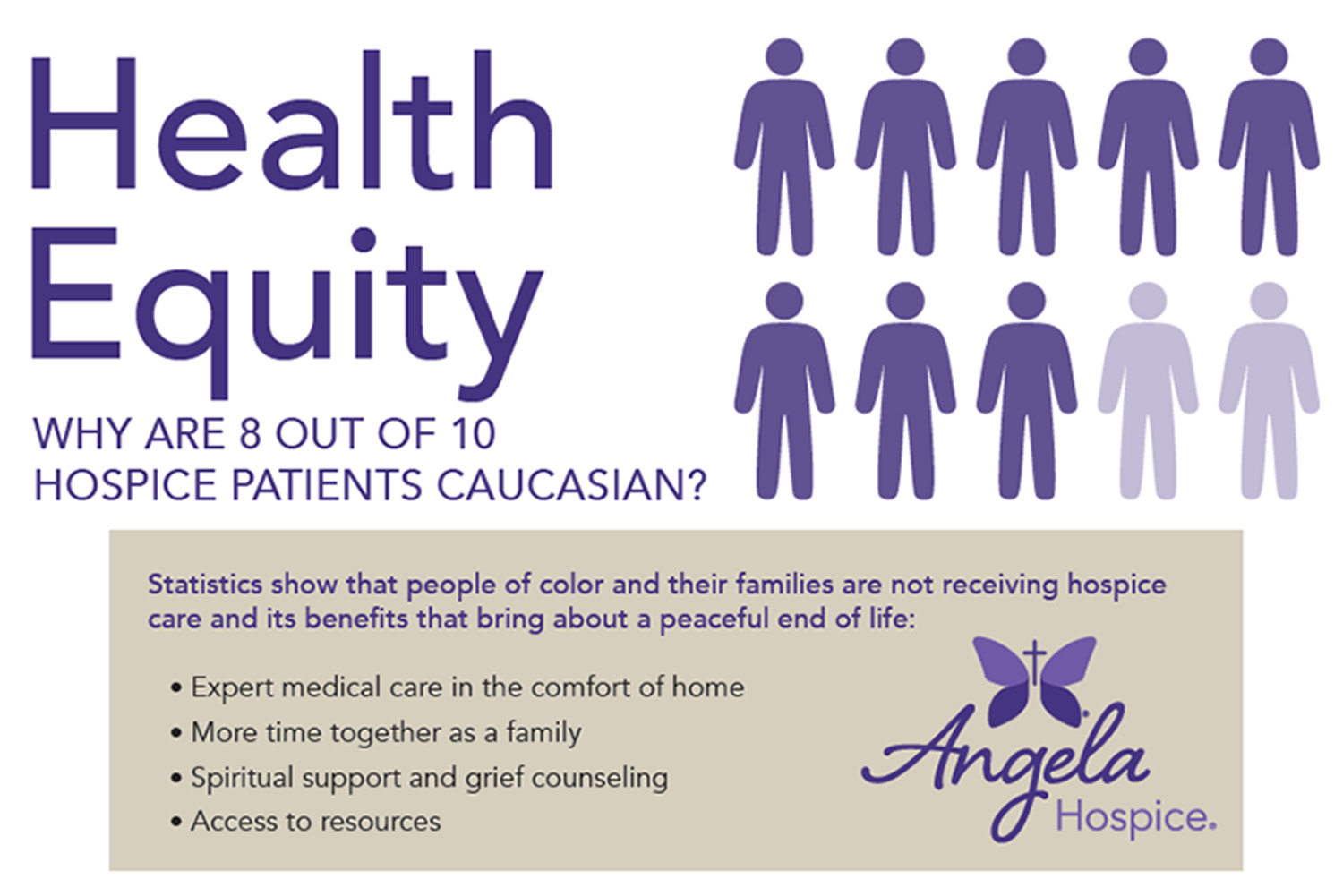

The Empowerment Project took root in a discussion among members of Angela Hospice's ethics committee about Black Americans being underserved by hospice. A doctoral student in ethics and philosophy prompted a conversation that led to a literature review that found many articles back up the concern.

Other research has reached the same conclusion, including a report published in 2017 in the American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine that identified many barriers to the use of end-of-life care by Black Americans such as lack of knowledge about prognosis, desires for aggressive treatment, family members' resistance to accepting hospice, and lack of insurance.

Rev. Smith sees another primary reason for the disconnect between Black Americans and hospice providers. She says many people of color have a distrust of the medical community that is rooted in historically being both denied care and exploited, including in the Tuskegee experiment that was revealed in the 1970s and in which syphilis sufferers were intentionally left untreated.

'How do we reach them?'

After the literature review, Angela Hospice's ethics committee surveyed the surrounding community to get residents' take on hospice care. The committee brought church leaders, academics, health care workers and elder residents into the conversation.

"We intentionally surveyed a diverse group of people to determine what their experience of hospice had been," Rev. Smith explains.

From there, the committee developed what Rev. Smith calls a "Hospice 101" presentation focused on hospice care, who qualifies, where it's offered, who provides it, how it's paid for, and bereavement and grief care services.

Then the committee took the presentation back to the people whose input had helped in the development. That group agreed that the information would be welcomed by the African American community.

"The next question was, how do we reach them? How do we share this information with them?" Rev. Smith says. "And the answer was the churches. So that's how they ended up doing the trainings in churches."

Point people

The training sessions started in 2017 for predominantly Black churches of any denomination near Livonia in suburban Detroit. The St. Francis Fund set up by the hospice's founding congregation, the Felician Sisters of North America, to support new initiatives based on shared core values provided seed money. The grant paid for the training resources and covered other costs in the project's early years. Angela Hospice has since taken over the costs.

Rev. Smith has been leading the Empowerment Project since she joined Angela Hospice in 2018. She says trainers approach church leaders to see if they are interested and supportive of hospice education for their parish.

"This is a very important feature of the project, because the minister is the driving force in the Black church and to go around the minister would be a mistake," she says.

The minister then decides who in the church should get the training and become the hospice point people for all church members.

Initially, the training was four in-person sessions, each on a specific topic: an introduction to hospice, advance directives, grief and bereavement, and "Ask the doctor," an open forum with a member of the hospice's medical team.

Later, the trainers added a fifth session on empathic listening and creating a safe space for fellow parishioners to talk about planning for death. "And that is the most important session after they understand what hospice is, given what their role is to be in the church, to walk alongside people who need this information," Rev. Smith notes.

Until COVID, the training sessions were biweekly and each started with a meal. Nowadays the trainers lead the sessions remotely. They also are open to modifying the timing and length of the sessions, to be respectful of participants' schedules, and to offering sessions on the topics of highest interest to the congregation.

At the end of the course, Rev. Smith presents graduation certificates to the trainees. "We do that during a church service, so that the church members know which members of their community have had exposure to this information and they could therefore go to someone in the church they trust," she says.

Fostering dialogue

Maria Holmes went through Empowerment Project training along with other members of Abundant Harvest Church of God in Christ of Belleville, Michigan. Pastor Willie S. Foster dubbed the training program the "11th Hour Ministry." The church posted information about the trainees on the bulletin board and website and spread the word that they're available to parishioners to discuss end-of-life issues.

Holmes wishes she had known about hospice in the 1980s, when she was a teenager and her father's health began to deteriorate as heart and lung disease and other illnesses took their toll. "I look back now and wonder, especially for my father, if hospice might have been helpful, but it just wasn't all that common then," she says.

Before she took the Empowerment Project training, Holmes had become something of a bereavement resource for family, friends and fellow parishioners.

"I realized after I lost my father-in-law in 2015 that a lot of families don't know what to do when they lose a loved one, if they've not been through that before," Holmes says. "So I actually put together my own personal spreadsheet to support friends and family. It's a list of what to do and how to find information and what you might need to prepare for during the death of a loved one."

She also shares templates for obituaries and funeral programs.

She found Angela Hospice's training to be a helpful addition to her knowledge base. In particular, she says she appreciates how it showed her and the other trainees how to open dialogues on sensitive topics.

"We feel like we're in a better position to understand and help other people," Holmes says. "And I think that it's a big part of what ministry does. And yet, oftentimes we're ill-prepared for it and or uncomfortable with it."

Hospice champion

Rev. Smith notes that hospice gained something of a poster child in 2023 when former President Jimmy Carter went into care. She says his candidness about his failing health and his championing of hospice until his death in December changed the perception of end-of-life treatment for many people.

"When people hear hospice, they feel that you sign on to hospice and you're dead," Rev. Smith says. "To be able to point to this experience that President Carter had has allowed the public to be aware of and actually helps to educate the public and opens the door for conversation about people being on hospice longer and not automatically dying when they sign on the dotted line. That, in and of itself, is a huge lesson about what hospice can be."