In February 2020, when a cruise ship arrived at a California port carrying passengers with COVID-19, the workers in the special pathogens unit at Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center and Children's Hospital in Spokane, Washington, were ready to help.

The unit is one of 13 spread throughout the country and designated by the federal government to treat high-consequence infectious diseases. They are known as Regional Emerging Special Pathogen Treatment Centers. Providence St. Joseph Health is the only Catholic health care system with a unit.

When the four COVID patients from the cruise ship who were under federal quarantine arrived at Sacred Heart's unit in the early days of the virus' spread, "There was a lot of response based out of fear," said Christa Arguinchona, a nurse and Providence special pathogens program manager. "And so, it was challenging for sure, but it was also an opportunity to educate everybody to our capability and to our preparedness level."

None of the four COVID patients brought to the unit had severe symptoms. They were released within the 28 days that the unit was activated. As more people were hospitalized later with severe cases of COVID, the unit was used as treatment space for the overflow of patients.

Sharing their work

This spring, after the federal government lifted the public health emergency, Providence opened the doors to the highly specialized unit for media tours. The system wanted people to learn about how the unit works

so they could understand how it was used, and how it may be used in the future.

Health leaders and federal partners look at specific criteria to determine when to activate and deactivate special pathogen units.

The units' origins go back to the Ebola outbreak in 2014 and 2015, when Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, the University of Nebraska Medical Center/Nebraska Medicine, and NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue in New York were tasked with caring for patients in the United States. Ebola first spread in parts of Africa, where more than 11,000 people died. Fewer than a dozen people were treated for it in the United States, where two people died.

The Ebola outbreak prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to partner with public health departments to create more regional facilities that would be able to respond in the event of a similar outbreak. Congress approved funding to establish the centers.

The Washington State Department of Health encouraged Sacred Heart to apply for funding. The hospital had the space and the willingness to invest in training and preparedness. Its unit opened in 2015, and generally serves Alaska, Idaho, Oregon and Washington.

Special equipment

The unit is 14,000 square feet, with 12 ICU-level rooms with negative airflow to contain pathogens. There's in-room video to help monitor and communicate with patients and caregivers, as well as a biosafety lab

to contain potentially infectious samples. An isolated area stores dedicated supplies and personal protective equipment and has rooms for putting on and removing the gear.

The unit also has a San-I-Pak, which is a sterilizer that allows workers to inactivate waste that may carry an infectious substance. Without the sterilizer, the waste would have to be taken to an off-site incinerator.

The number of patients the unit can hold at one time depends on the pathogen involved. The unit can hold only two patients with Ebola or viral hemorrhagic fever because of the space needed to isolate them at a high level. The unit can care for up to 12 patients who have a respiratory pathogen with a lower acuity.

Prepared for a pandemic

Arguinchona was at a meeting in January 2020 unrelated to COVID with colleagues from the other regional treatment centers when they started carefully monitoring the novel virus seen in Wuhan, China. Because

the Spokane unit's staff had been regularly training for years, preparations for their first patients went smoothly.

"This happened to be an emerging novel pathogen that we really didn't know much about yet," she said. "So, it was a perfect use of our space and our expertise."

She said that no staffers contracted COVID during the unit's activation — a testament to their preparedness.

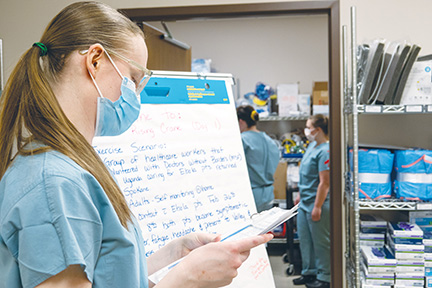

About 90 staffers, who otherwise work elsewhere in the hospital, are specially trained to work in the unit. They include nurses, doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, respiratory therapists, medical laboratory scientists and environmental services personnel. They get regular training and can mobilize within eight hours if they are asked to receive a patient with a high-consequence infectious disease. They all chose to work in the unit.

The unit's staff partners with those in other regional centers to educate and train one another. This March, they completed a training exercise with another health care system in the Spokane area as well as with other local and state agencies. Now, they are working with the other regional centers to focus on prevention of disease spread.

Arguinchona called the time during the unit's activation challenging, but not scary. "I would say we were confident, and we were ready," she said. "And I'm confident that we would feel the same way again, if we were activated for another pathogen."

Thomas Barnett is a nurse who joined the special pathogens team around the time it started and found it especially rewarding to be part of a new program at the hospital. He serves as a team leader and takes part in quarterly trainings.

"A lot of my colleagues I've worked with, I've tried to get them to join and they were like, 'Do you really want to take care of an Ebola patient if they come?'"

Barnett said his response is: "The way I look at it, I'm getting the best training to be safe. It's not that I want to take care of somebody who is really contagious, but I know how to do it."

When he and his colleagues in the unit learned in 2020 they would get some of the first COVID patients, they felt ready. "It was almost like a nervous excitement," he said. "Like, OK, we don't know what this virus is just yet, but I did feel very confident that we had all the right equipment. We'd had lots of training. We were familiar with the unit we were using."

Preparing for the future

Leaders of the National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center, the coordinating body for the National Special Pathogens System, said in a statement that they are proud to have members

of the Sacred Heart unit in its ranks. The leaders added that they "remain grateful that the Providence Sacred Heart special pathogens unit will continue to join NETEC and the nation's 12 other RESPTCs (Regional Emerging Special Pathogen Treatment

Centers) in setting the gold standard for special pathogens care, protecting the lives and security of millions of Americans in the process."

Taking on the responsibility of the special pathogens unit is one way Sacred Heart fulfills its mission as a Catholic hospital, Arguinchona pointed out.

"We are very committed to our mission, and our mission is to care for our community and to care for those that are vulnerable," especially those with infectious diseases, she said. "We can't control who walks through our doors, and we want to be prepared for whoever is sent to us needing that care."