Lacey Starcevich was 19 years old when she showed up at the emergency room at St. James Hospital in Butte, Montana, with a bladder infection. She didn't have a home, she was addicted to drugs, she was severely underweight, and, as she eventually found out, she was 11 weeks pregnant.

She felt like her world was crashing down around her. At her first appointment with an obstetrician, social worker Joslin Hubbard came in to talk to her.

"She was very caring and sweet and she made me feel not judged," said Starcevich. "Not one ounce of me wanted to be in that room. And she just made me feel like I was welcomed, like I needed to be there."

Hubbard explained to her the importance of the first 1,000 days of a mother and baby's life, and that there was hope and help for her and her baby.

Hubbard helped start the First 1,000 Days program at St. James in southwestern Montana, part of Intermountain Health. The program seeks to screen pregnant patients and connect them to the help they may need and follow them through their pregnancy and the first two years of their child's life. The program name comes from the length of a typical pregnancy (270 days) plus the first two years of the baby's life (365 days plus 365 days).

"This first 1,000 days is a critical and crucial time in human development," said Hubbard in an interview with Catholic Health World. "It's a great time for you to be able to set up your child for success later in life. We tried to come at it as a positive — which it is. It's an opportunity in positivity, or a positive chance to impact life."

The program started in 2018 when the hospital got a grant from the Montana Healthcare Foundation to provide care coordination to help support social determinants of health, specifically ones around substance use and mental health needs.

Intermountain Health runs a similar program out of the midwifery clinic at St. Vincent Regional Hospital in Billings, Montana, and is working to get a program off the ground at Holy Rosary Hospital in Miles City, Montana.

Hubbard, who now works as an ER navigator for St. James, helped get First 1,000 Days rolling while she was an OB care coordinator.

In February, Hubbard and Starcevich joined April Ennis Keippel, Intermountain Health director of community health, and Jana Distefano, director of community health for Professional Research Consultants, in describing the First 1,000 Days program on a panel. The panel was at the American Hospital Association's Rural Health Care Leadership Conference in Orlando.

Fighting against adversity

Butte is a mining community, and in its heyday, it was the largest city between Chicago and San Francisco. "People from all over the world came to work in the copper mines," said Keippel. "It was known

as the richest hill on earth."

But it was dangerous work, and a "live for today" attitude has prevailed through the generations, she said.

In a 2023 community health survey, more than 42% of women in Butte-Silver Bow County, where most residents are white, reported symptoms of chronic depression. Nearly half of all surveyed were low income. Nearly half of women reported their life has been negatively affected by substance abuse, either their own or somebody else's. Many of the women in crisis were of childbearing age.

Compared to other states, Montana has the third highest percentage of children who have experienced two or more adverse childhood experiences, such as living with someone with an alcohol or drug problem and being a victim or witness of neighborhood violence.

"If you don't have a way to intervene, that cycle continues multiple generations over," said Keippel. "I think that's what we've seen in the Butte community. So the First 1,000 Days project is really a way to intervene, where you can kind of break that cycle, and be able to provide the change or resources to change. For some people, I think, if you've never known anything else, how would you envision a different world for yourself?"

How the program works

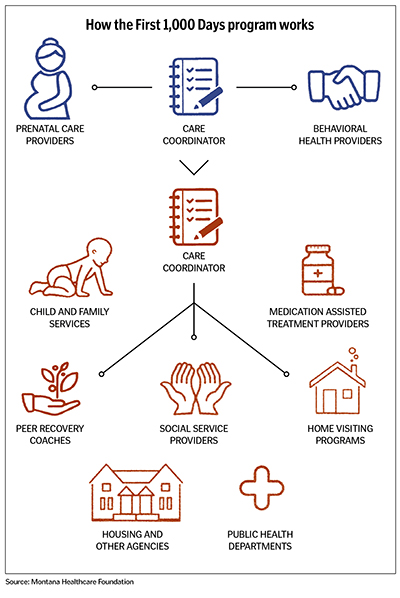

The idea of the First 1,000 Days program is to connect pregnant patients with resources that they didn't know were available and that caregivers might not have known the patients needed. Care coordinators work

directly with the patients, and others with the hospital work with community partners to coordinate care and try to address issues.

When patients are in the waiting room, they are given a questionnaire that asks about their home life, whether they have adequate housing and transportation, are feeling symptoms of prenatal depression, or if they are experiencing domestic violence. A nurse collects the questionnaire when the patient comes into the exam room, and the care coordinator goes through it with the patient, addressing and discussing issues behind the answers.

If a woman misses prenatal appointments, it may not be because she doesn't care, it may simply be because she doesn't have a way to get there, said Hubbard.

If a woman pregnant with her second child reports she experienced postpartum depression after her first, care coordinators with the program may be in touch with her more often after she has her second baby to look for signs of trouble.

It isn't always obvious who needs help.

We would have labor and delivery nurses that we would screen, and they would say, 'You know, I think I had postpartum depression with my first baby. This is my second, but I was too scared to say anything. I wasn't sure,'" said Hubbard.

Expectant mothers who had previous miscarriages or infertility issues also might need help because if they do experience depression and anxiety, they might be afraid to tell anyone because they worked hard to achieve this pregnancy, said Hubbard.

How often the care coordinator or care providers follow up with the woman depends on the need.

Tools for success

Starcevich didn't have insurance when she found out she was pregnant, so Hubbard helped her enroll in Medicaid, an outpatient drug treatment program, and a nurse-family partnership so that she could get regular

care. She got clean within a week and moved into her boyfriend's parents' home.

She said Hubbard "gave me all the tools to set me up for success."

Her son, Raiden, is now 4 years old. She and her boyfriend, Jim, got married, and they have a second son, Parker, who is 2. They both have jobs and a home, and life is good. They are teaching Raiden how to snowboard. And, as she told the attendees at the panel at the conference in Orlando, she still texts Hubbard for support.

The First 1,000 Days program, Starcevich said, saved her life.

"It not only saved me and Raiden, it helped me create the family I have today," she said.

There are other successes: St. James Hospital has seen fewer babies born with a positive neonatal drug screen, a large increase in mothers who have received adequate prenatal care, and a smaller percentage of newborns removed by child protective services. In some cases where a newborn cannot live with the mother, the outcome may not be as traumatic when the mother gets help from the First 1,000 Days program because the care coordinators have discussed the options with the mother during her pregnancy. The mother may have arranged for an open adoption or otherwise been more involved in making the decisions, said Hubbard.

Keippel said the program's focus on helping the poor and vulnerable aligns with the system's mission.

"Intermountain's mission is really about helping people to live their healthiest lives possible," she said. "But for Catholic care sites, ours is really about revealing and fostering God's healing love. I just think this is a great example."

Hubbard urges any system that would like to start a similar program to start small, even by screening a small category of patients and families. And she said providers should remember that these women want to do well and want to love their babies in a way they may have never been loved themselves.

"As an organization, we can't solve everyone's issues, but we can give them compassion and empathy and understanding and love," she said. "And those are sometimes the greatest gifts that we can give individuals."