Doctors say symptom cluster differs by patient, so care must be customized

The COVID-19 virus had been circulating for only a short time when Dr. Nilam Srivastava and her colleagues at Saint Peter's Healthcare System recognized that some hospitalized patients would require extensive management of medical complications from the infection after discharge.

"We had already started identifying their needs while they were in the hospital, I would say from late May (2020)," said Srivastava, chief of the New Brunswick, New Jersey-based system's division of general internal medicine.

In August 2020, the system launched its COVID-19 Recovery Program, which Srivastava co-directs with Dr. Amar Bukhari, chief of the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine, and associate chair for the Department of Medicine at Saint Peter's University Hospital. The program has coordinated treatment for about 800 patients among primary care doctors and cardiologists, pulmonologists and other specialists. Not all of the patients had had severe bouts of COVID. Some were even asymptomatic in the acute viral stage yet wound up with long COVID symptoms such as fatigue, labored breathing, brain fog, headaches and insomnia that have required ongoing care.

While much remains unknown about COVID and its lingering complications, Srivastava said one thing that is clear is that the complications manifest in different ways in each patient. Symptoms vary in number, duration and severity. Some patients need only one type of treatment, such as respiratory therapy to rebuild lung capacity, while doctors choose from a cafeteria line of therapies for others depending on the specific secondary conditions caused by COVID infection. Some patients receive physical therapy, neurocognitive evaluations, physiatry referrals and/or undergo mental health counseling for depression and anxiety rooted in COVID infection.

Srivastava said Saint Peter's works to address all of its long COVID patients' medical needs and their goals of care in a coordinated way. "The recovery is different in each person," she said. "We have to individualize the treatment and that is important. It's not one treatment fits all."

National response

Doctors with Catholic systems that don't have a dedicated long COVID clinic or program said they too are working across disciplines to provide symptom-specific care.

Officially long COVID is called post-acute sequelae SARS-CoV-2 infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines the condition as "a wide range of new, returning, or ongoing health problems people can experience four or more weeks after first being infected with the virus that causes COVID-19."

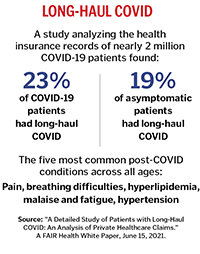

Estimates of how many COVID patients contend with lingering symptoms vary widely. One CDC study published in September and based on a survey of 698 adults who had tested positive, said that about two-thirds of those respondents self-reported symptoms that lasted beyond four weeks. The CDC study also noted that the prevalence of lingering systems has been reported as being as low as 5%. Even at the low end of the estimate, based on reported COVID infections, the number of U.S. patients with long COVID symptoms of varying severity would approach 4 million. The CDC study calls long COVID "an emerging public health concern."

The condition has prompted various national responses. The National Institutes of Health in September awarded nearly $470 million in grants for an initiative called REsearching COVID to Enhance Recovery, or RECOVER for short. The goal is to build a national study population and support large-scale research on COVID's long-term effects. As part of its National COVID-19 Preparedness Plan released in March, the White House pledged "to accelerate efforts to detect, prevent, and treat Long COVID."

Srivastava said Saint Peter's is collecting data on the patients in its long COVID program for its own analysis and to inform its treatment. It is not partnering on any larger studies, although she said that is under consideration.

Treating and collaborating

Dr. José Biller is professor and chair of the department of neurology at Loyola University Medical Center in suburban Chicago and Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. He co-leads a specialty neurology clinic for long COVID patients that opened in January 2021. The medical center is part of Loyola Medicine — a three-hospital system within Trinity Health.

Through mid-February, the Loyola neurology clinic had evaluated 113 long COVID patients. The first step in assessing their health was an extensive intake questionnaire that covers a long list of potential symptoms. So far, about three-fourths of the clinic's patients have reported "crushing chronic fatigue" and/or brain fog, or the inability at times to comprehend or multitask. More than half have reported anxiety, headaches and insomnia.

Biller is using findings from the clinic's patients in collaborative studies with other physicians and researchers into the incidences, potential causes and best treatments for long COVID. One of them, published in June in the journal Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, includes proposed diagnostic criteria and symptom-based care for long COVID.

Biller said it would be premature to point to any definitive conclusions about the cause of long COVID and potential cures. He is, however, confident about some aspects of the condition, such as that it is linked to the novel coronavirus, and not just occurring by coincidence in patients who have contracted the virus. He also is certain that COVID vaccines don't trigger long COVID, although he said it remains unclear whether those vaccines might offer some protection against the syndrome.

In addition, Biller is certain that the best care for patients is multidisciplinary, because the symptoms often span organ systems, and multimodal, with a mix of medication and other therapies such as those that focus on nutrition, sleep and coping with stress that is tailored to each patient's needs.

Starting with primary care

Bon Secours Mercy Health partnered with The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center for a symposium on long COVID in April 2021. The system's physicians, nurses, social workers and other associates were among more than 600 people who spent a Saturday morning learning about risk factors and the constellation of symptoms associated with the syndrome as well as the role of exercise, therapy, pain management and nutrition in treatment.

"I think people walked away realizing this is a syndrome that's evolving with focus areas that involve different specialties," said Dr. Herb Schumm, Bon Secours Mercy Health's vice president, medical director education and physician engagement.

Bon Secours Mercy Health is participating in another long COVID educational event on April 2 that is open to anyone.

Schumm said the system's doctors are noting similar patterns that have been identified in early studies on long COVID, including that older patients and those with preexisting conditions such as diabetes or compromised immune systems often have the most severe lingering symptoms after a bout with COVID.

Bon Secours Mercy Health is relying on its primary care providers to manage treatment for long COVID patients. Those providers have established referral paths to link patients to appropriate specialists, Schumm said.

He expressed concern that since so many providers themselves contracted COVID, the already-depleted health care workforce faces another headwind from long COVID. "From an employer standpoint, I'm not sure we're ready for this or equipped for this broader range of potential disabilities," Schumm said.

Dr. Shephali Wulff, system director of infectious diseases at SSM Health, also has taken note of long COVID's impact on care providers. She has seen nurses struggle to return to demanding 12-hour hospital shifts. Some of those nurses have had fatigue as long as nine months after recovering from acute phases of COVID.

Just how long long-term COVID symptoms last is one of the many unknowns about the condition, Wulff said. "It's still an area of growing science and so I think we're all learning together from our patients."

'When will I feel better?'

SSM Health doesn't have a long COVID program, per se; its primary care providers make referrals to specialists based on patients' symptoms. To inform their care, Wulff said SSM Health clinicians are watching closely how their long COVID patients respond to treatments, taking part in CDC trainings and staying on top of studies published by JAMA and other trusted sources to inform their care.

Wulff said long COVID patients are proving to be less resource-intensive than patients with severe cases of COVID. Few of them require hospitalization. Nevertheless, she said, while knowledge around the condition evolves, the lingering symptoms are frustrating for patients and clinicians.

"Everyone wants to know 'When will I feel better? When will these symptoms go away? When will I go back to normal?' and we don't know and that's a really difficult place for both the patient and the clinician," she said.

Research team finds four early indicators of long COVID

A team at the Institute for Systems Biology, a nonprofit biomedical research organization affiliated with Providence St. Joseph Health, has identified four factors that can be measured at the point of a COVID-19 diagnosis that indicate whether the patient will have lingering illnesses related to the virus.

The team published a paper on its findings titled "Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae" in the journal Cell on Jan. 24. The paper's findings have been cited in many media reports, including by The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Scientist magazine.

The factors the team identified are:

- The presence of certain autoantibodies, which are antibodies produced by the immune system that are directed against one or more of the body's own proteins.

- Preexisting Type 2 diabetes.

- The level of the COVID-19 virus in the blood.

- The level of Epstein-Barr virus in the blood.

Dr. Jim Heath is president of the Institute for Systems Biology and a co-author of the research paper. In a Q and A that appears in the spring 2022 edition of the CHA journal Health Progress, Heath says the research found that patients with any of the risk factors had odds greater than 90% of having long COVID with three or more symptoms.

The study also pointed toward potential treatments. For example, Heath says in the Health Progress article: "I think it is worthwhile to begin exploring whether drugs that are effective for lupus erythematosus might also have a role in treating patients with long COVID."

— LISA EISENHAUER

After two bouts with COVID, lingering symptoms test man's endurance

Just as he was getting back to feeling like himself after a bout with COVID-19 that had sent him to the mat for months, Michael Heath contracted the virus again.

Michael Heath says his wife, Deedee, and daughter, Emily, are bucking him up during his slow recovery from long COVID. Heath has had migraines, severe fatigue and labored breathing since contracting COVID-19 twice, most recently in August 2020.

Michael Heath says his wife, Deedee, and daughter, Emily, are bucking him up during his slow recovery from long COVID. Heath has had migraines, severe fatigue and labored breathing since contracting COVID-19 twice, most recently in August 2020.

"That was devastating for me because I'm thinking I just had this battle for all those months and now here we go again," recalled Heath, a social worker and freelance photographer who lives in Baraboo, Wisconsin.

Heath believes he caught COVID the first time while photographing a wedding. He remembers waking up the day after — March 1, 2020 — and feeling extreme exhaustion. He'd expected to be tired after logging 29,000 steps the day of the wedding. He didn't expect to be unable to get out of bed.

"It was something I had never experienced before," the 53-year-old said. "It came on me that quick."

Over the next few days, he grew more miserable, with relentless migraines, lack of appetite, night fever, labored breathing, heart palpitations and constriction in his throat that made swallowing difficult. Heath went to the emergency room where a doctor who had greeted him in full-body protective gear left the room and then called the phone in the room to talk to Heath.

The doctor said that while he was certain Heath had COVID, because Heath didn't have a fever he couldn't, under the protocols in place, do a test. The doctor also had no treatments for Heath. He urged Heath to rest, isolate and continue the use as needed of an inhaler that Heath had for occasional allergy-related asthma. Until he came down with COVID, that mild asthma was Heath's only health issue.

Heath went back to the ER twice more in spring 2020 when he was struggling to breathe. Each time he was sent home without being hospitalized with the same advice as the first time. There were no COVID therapies available at the time.

By July, Heath said he was feeling like he had turned a corner. Though his headaches, fatigue and breathing problems weren't gone, they had eased considerably.

He accepted another photography assignment that put him in close proximity to a mother and two teenagers. Even before the mother alerted him two days later that the kids were sick, he recognized that his acute COVID symptoms were back.

It took a few days before Heath's suspicions were confirmed by a positive test result. The second time the virus seemed to clear his system faster than it did the first time, Heath said. The fever and chest congestion lasted just a few days.

Nevertheless, his body has yet to recover from the double blow. He endures severe fatigue, breathing and swallowing problems, migraines, heart palpitations and cognition challenges that were not present before his COVID infections.

His primary care physician — Dr. Randy Krszjzaniek with SSM Health Dean Medical Group in Baraboo — has sent Heath to a neurologist, cardiologist and other specialists. "He was my savior and my blessing in this whole journey with COVID because he referred me to countless specialists to have me tested and treated to check my heart, to check my lungs, to check my breathing, my swallowing," Heath said of Krszjzaniek.

Heath has undergone EKGs, CT scans, MRIs and an ultrasound to diagnose and assess his condition. Some of them, he said, show no evidence of problems — a frustration for him and the doctors. He started pulmonary rehab to rebuild his lung capacity and strength, then had to take a break because the sessions caused his heart rate to spike.

Still in the throes of long COVID, Heath believes he's making progress. He's hopeful that he'll return to close to what had been a healthy life. He credits his wife, Deedee, adviser for the GoldenCare program for seniors and patient care advocate at SSM Health St. Clare Hospital in Baraboo, and their 15-year-old daughter, Emily, for helping him stay focused on healing and optimistic during his slow recovery.

He worries, however, that he will never again be fit enough for strenuous activities like the long hikes, biking and swimming that he used to enjoy a couple of years ago.

He also is concerned that many people don't take the long-term risks of COVID seriously. It's one reason why he shares his story.

"The general community I feel they just think, 'Oh it's the flu or a cold and you get over it and there's a 98% or whatever survival rate,'" Heath said. "Yeah, the survival rate, thank the Good Lord, is high, but survivors that get long COVID some have lost their jobs, their livelihoods. It's really a sad state."

— LISA EISENHAUER