Over the past three years, facilities within Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System have been refining protocols, creating patient pathways and using a new test to detect and manage sepsis.

Data show that the changes are having a significant positive impact on patient outcomes and saving lives, according to Dr. Christopher Thomas, vice president and chief quality officer at FMOLHS. The Baton Rouge, Louisiana-based system has 10 hospitals and a network of affiliated outpatient facilities in Louisiana and Mississippi.

"Our goal has been to create a new structure that treats sepsis like the other time-dependent diseases for which medicine has found success, like acute myocardial infarction, stroke and trauma," Thomas said. "Each of these diseases has a well-defined approach for identifying patients at risk and following that with an objective diagnostic test upon which treatment is dependent."

He said applying these concepts to sepsis, FMOLHS has shown "we can improve both patient-centered outcomes, including mortality and length of stay, while reducing resource use."

Disparate impact

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1.7 million adults in America develop sepsis annually. About 350,000 adults diagnosed with the condition die each year while hospitalized or are discharged to hospice. About one-third of people who die in the hospital had sepsis during their stay.

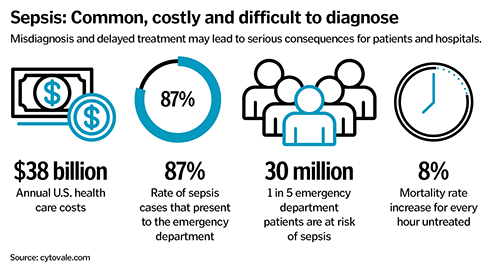

The condition, which is characterized by organs failing because of the body's poor infection response, is a leading cause of mortality and a significant driver of health care costs, according to FMOLHS. The system says that historically, sepsis has been difficult to diagnose because of the lack of reliable diagnostic tools and because it presents similarly to many other conditions.

Thomas said awareness of and concerns about sepsis have increased over the past several years. Despite the increase in awareness, clinicians' ability to accurately diagnose sepsis "has not kept pace with the other time-sensitive diseases," Thomas said.

Thomas added that addressing sepsis' impact is key to creating true health equity because marginalized populations can have higher rates of comorbid diseases such as heart failure and kidney disease. Research reported by JAMA Network Open in October indicates that such factors make compliance with severe sepsis and septic shock management protocols more difficult. Thomas believes the use of early diagnostics may be the key to closing the health equity gaps.

Professional clinical societies have worked to address the sepsis crisis, including by releasing consensus guidelines in 2021 under the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. And then in 2023, the CDC launched a sepsis core elements program to improve how hospitals manage sepsis.

Professional clinical societies have worked to address the sepsis crisis, including by releasing consensus guidelines in 2021 under the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. And then in 2023, the CDC launched a sepsis core elements program to improve how hospitals manage sepsis.

Novel test

FMOLHS' flagship hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge, has been leading the system's efforts to stay at the forefront of sepsis knowledge and protocols. In 2022, that facility launched a Sepsis Learning Health Initiative, educating and training clinicians on a holistic approach to diagnosis and treatment that included comprehensive data collection.

In August 2023, Our Lady of the Lake integrated use of the IntelliSep test from the Cytovale medical diagnostics company into its sepsis protocols. Thomas, along with Dr. Hollis O'Neal, spearheaded the hospital's involvement in developing, testing and implementing the novel test for sepsis. O'Neal is FMOLHS medical director of research.

Based on the success of the innovations at Our Lady of the Lake, FMOLHS replicated them in summer 2024 at St. Dominic Health in Jackson, Mississippi; and in Louisiana at Our Lady of Lourdes Health in Lafayette, St. Francis Health in Monroe, and St. Elizabeth Health in Gonzales.

Nurse triage

Thomas said the protocols adopted at these FMOLHS sites include "a structured process for screening" with a patient-centered approach that uses a diagnostic, the IntelliSep test, to risk-stratify patients for sepsis. The facilities then use "provider-driven treatment pathways that are informed by the diagnostic," he said.

He explained that FMOLHS' approach differs from how many health care facilities take on sepsis. It is common for facilities — following protocols established by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services — to treat a broad swath of incoming patients in the emergency department as if they have sepsis based on an overabundance of caution and a fairly indiscriminate process for determining risk of sepsis.

However, Thomas said, given that not all these patients are prime candidates for aggressive sepsis treatment, this can be a waste of time and resources. Waste is especially concerning in the emergency department environment, where time squandered on a wrong diagnosis can be life-threatening. Additionally, with limited staff and resources, inefficiency can be very costly.

Part of FMOLHS' innovations is a triage system in which a nurse completes a verbal screening of patients in the emergency department, taking into account their health history, potential symptoms of infection and vitals. Only patients with signs and symptoms of sepsis get the IntelliSep blood test, which calculates in about eight minutes how likely a patient is to have sepsis. According to the IntelliSep website, the lab test analyzes "biophysical changes in white blood cells that occur early in the immune response to infection and signal risk for sepsis."

Based on test results, patients then are categorized as "band 1" for patients unlikely to develop sepsis, "band 2" for those with a possibility to develop it, and "band 3" for those who will probably develop it. Patients in band 1 are evaluated for other diseases, patients in band 2 are monitored further for sepsis with clinical imaging as needed, and patients in band 3 are put on an aggressive treatment path, including the administration of antibiotics.

Thomas said that implementing sepsis treatment only for those at objective biologic risk of it is a much more efficient and effective use of health care staff and resources, improves the chances that clinicians are acting on a correct diagnosis, and decreases the likelihood that unconscious bias will impact the diagnostic process.

Care improvements

Data analysis shows that after using the new protocols FMOLHS has achieved a 4.3% reduction in sepsis-associated mortality, a 0.76 day reduction in the length of patient stays, and a significant reduction in return visits to the emergency department. The health system also saw a significant reduction in the use of unnecessary blood cultures, thus saving time and resources. The system also increased the rate of emergency room discharges among the group unlikely to develop sepsis. There also was a reduction in the cost of care.

Given that there is an 8% mortality rate increase for every hour a patient remains untreated, according to the IntelliSep website, and given that sepsis can have lasting consequences for those who survive it, treating patients quickly is essential. Having a protocol that promptly determines patients' risk level and gets those truly at risk of sepsis into treatment without delay is vital, said Thomas.

FMOLHS plans to help other hospitals implement the protocols and tools it is using.

Thomas noted that improving sepsis outcomes requires collaboration among doctors, nurses, quality and performance improvement professionals, the lab, the pharmacy and other units.

"We have felt really good" about the results, he said.

Thomas is part of a research team that recently published the study, “Impact of a Sepsis Quality Improvement Initiative on Clinical and Operational Outcomes,” in the MDPI healthcare academic journal.