Mercy is using a standardized reporting system, prompt responses, and, sometimes, a conversational approach to try to put a quick end to disruptive physician behavior.

The Chesterfield, Missouri-based system has developed two programs within its systemwide harm reporting tool — Safety Accountability and Feedback for Everyone, or SAFE — that specifically track and seek to counter problematic physician behavior.

Dr. Chad Smith and Kathryn Nelson, who have roles at Mercy connected with SAFE, say disruptive physician behavior while rare can pose a direct threat to patient safety, have a negative impact on patient outcomes, and put the safety and well-being of the offending physicians' colleagues at risk. They say the reporting programs are designed to get at the root of problematic physician behavior in a constructive way, while promoting the well-being of everyone involved.

"This work shows we care about protecting patients from harm and about having safe workspaces for co-workers," says Nelson, Mercy chief quality officer.

Smith, chief medical officer at Mercy Hospital Oklahoma City and a system-level physician leader, adds, "It all conforms with our mission statement and core values. We're seeking to improve everyone's experience, we're seeking to understand the situations that are going on, we're focusing on right relationships. We're affording providers an opportunity to learn and grow and be enriched" in the process of addressing problematic behavior.

Two reporting channels

The SAFE reporting system allows Mercy to receive reports on, track and seek to resolve tens of thousands of safety events — including falls, medication mishaps and care coordination missteps — each year across its eight-state footprint. The Vanderbilt Health Center for Patient and Professional Advocacy helped Mercy design two programs within the SAFE reporting system for receiving and processing potential safety events involving doctors and advanced practice providers: the Patient Advocacy Reporting System, or PARS; and the Coworker Observation Reporting Systems, or CORS. Mercy has more than 5,000 physicians and advanced practice providers across Arkansas, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Texas.

Smith says there are multiple ways the Vanderbilt center helps Mercy use the information in the patient and co-worker reporting systems. Mercy and Vanderbilt continuously monitor incoming reports, and in cases in which a report in PARS or CORS is on an imminent or serious threat to patient or co-worker safety, Vanderbilt immediately alerts Mercy, and Mercy leaders work to resolve the issue at the root level.

Vanderbilt and Mercy also use the data to analyze trends and identify systemic issues that need to be addressed to improve quality and safety at Mercy.

Smith and Nelson say some top goals of these reporting systems are to create a positive culture of patient safety, validate and investigate problems as they arise, maintain transparency in safety reporting and in the resolution of problems, and ensure patients and employees feel heard.

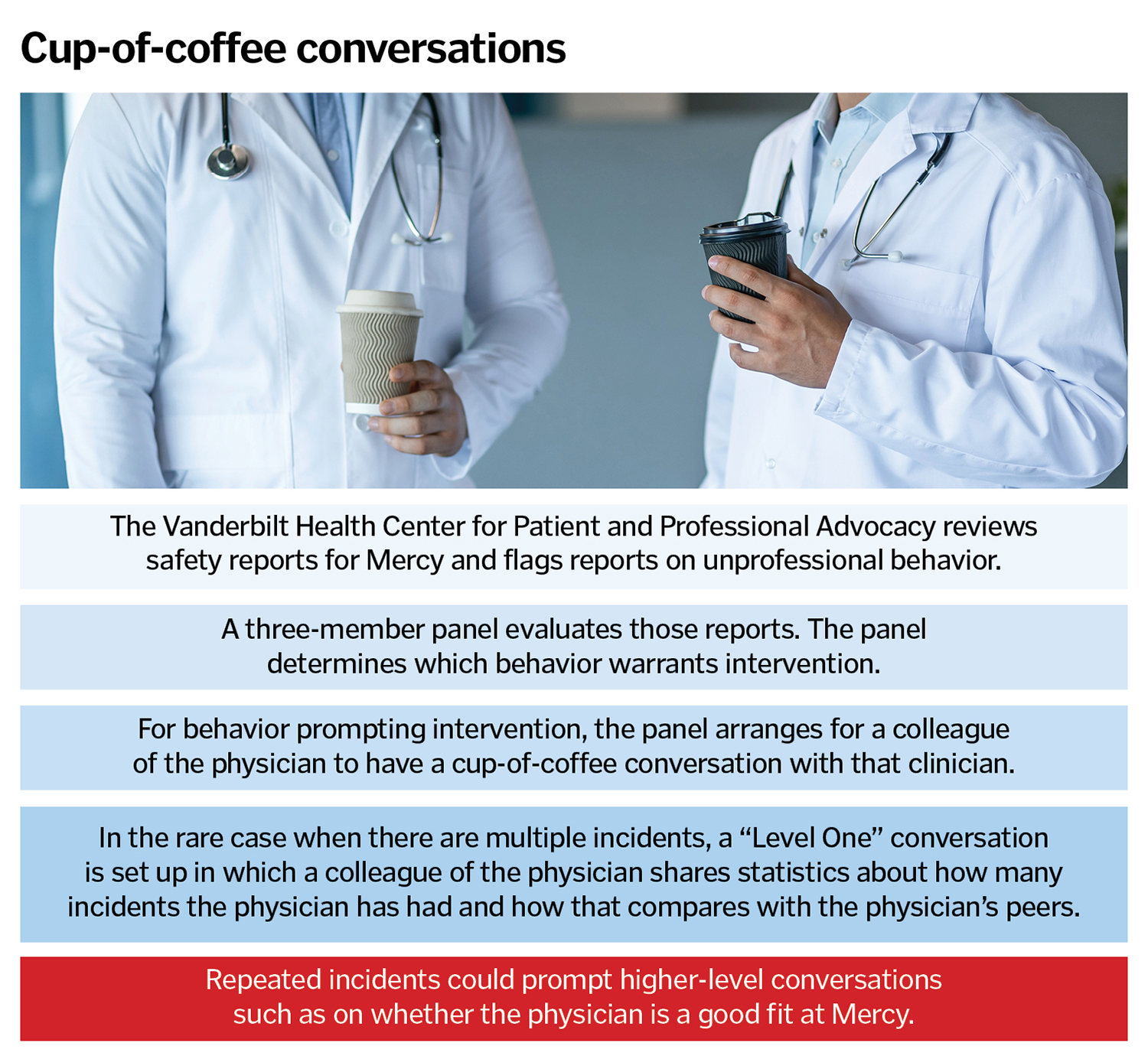

As the Vanderbilt center is culling through reports coming through the CORS system, it flags those that have to do with physician or advance practice provider unprofessional behavior, such as inappropriate language or actions toward co-workers. Once the Vanderbilt center staff deems behavior unprofessional, they send the relevant report plus additional information about whether the provider has been flagged before to a three-member committee that includes Smith. That committee evaluates the report and if committee members agree that the behavior is unprofessional, they arrange for a peer to have a "cup-of-coffee" conversation with the provider. Peers are trained in advance on how to have a collegial, nonjudgmental, brief conversation with the provider to make that person aware of the report.

In the cup of coffee conversations, the provider does not have to defend himself or herself, nor is it a contentious exchange. The practice of meeting over a cup of coffee harkens back to a convention of Mercy's foundresses, the Sisters of Mercy. They would talk about important — and potentially difficult to discuss — topics over a cup of tea.

Smith says the peer intervention normally resolves the concern and it is rare for the provider to be reported again.

Mercy promotes the "comfortable cup of tea" approach across its ministry, with the concept inspiring the name of the Comfortable Cup Cafe at the Love Family Women's Center. That center is on the campus of Mercy Hospital Oklahoma City. The "comfortable cup" concept is a Sisters of Mercy congregation tradition that originated with the foundresses talking through concerns over a cup of tea. The concept is at the heart of the health system's approach to handling concerning physician behavior as well.

In the unusual case that a provider is reported again, Smith says, a similar process repeats itself except that the peer receives additional data to give to the provider. In this "Level One" conversation, the peer gives the provider analysis showing how the physician ranks against his or her colleagues when it comes to reports of unprofessionalism. Smith explains that Mercy takes this step in the process because many physicians have a competitive spirit, and the desire to rank better can drive them to change.

According to Smith, there have been about 2,000 cups of coffee conversations and about 200 Level One conversations over the past nearly two years.

In the very rare case that reports of unprofessionalism continue after the Level One conversation, the committee Smith is on then engages physician leadership to have more substantive conversations with the provider. These could be conversations about whether Mercy and its values are really a fit for the physician. Or they could be conversations about what is prompting the poor behavior — is there a physician wellness issue, is it a workload issue, does the physician need some type of behavioral intervention?

Smith says Mercy has many employee assistance programs available to physicians who are experiencing burnout, behavioral health concerns and other stressors.

Return on investment

Nelson mentions that Mercy is very clear to its employees, including in onboarding and ongoing communications, that unprofessional behavior will not be tolerated, and that co-worker safety has top priority.

Mercy has been equally clear that the process it uses to address such behavior is rooted in Mercy values and is aimed at the growth and the protection of the well-being of the colleagues involved.

Nelson notes that a key benefit of the system is the ability to track physician behavior, monitor progress and benchmark results. The whole system is aimed at reducing harm.

Since launching PARS and CORS about eight years ago, Mercy has seen improved patient outcomes and a decrease in the number of malpractice lawsuits brought against the system.

Smith says that Mercy is taking on harm reduction and addressing unprofessionalism in a consistent, intentional way.

"To have a robust approach to patient safety, we have to understand that people are human and will make mistakes," he adds. "Our job is to have enough fail safes in place so when problems do occur there are no negative effects on patients.

"And we can do these types of programs in a way that also upholds our Catholic tradition."