BY: JOHN O. MUDD, J.D., J.S.D.

Leadership Formation Takes Leaders to New Levels

Dr. Mudd is senior vice president, mission leadership, Providence Health & Services, Renton, Wash.

Not long ago in Catholic health care we spoke commonly of the importance of "leadership development" to prepare lay persons to be effective leaders in the ministry. Increasingly we speak today of "leadership formation."1 What does the subtle shift in language imply? What are the differences and similarities between leadership development and leadership formation?

Clear answers to these questions have not yet emerged, but with programmatic advances of the past several years, an understanding is emerging regarding elements that need to be in the development and formation of leaders in Catholic health care.2

To help focus their efforts, Catholic systems and individual ministries have adopted sets of leadership competencies, most of which contain common or overlapping characteristics. In its landmark study, first published in 1994 and updated five years later, the Catholic Health Association identified competencies found in highly effective leaders in Catholic health care.3 Although these competencies are often referenced and used in Catholic ministries, what has not yet emerged is a commonly used conceptual framework in which the competencies can be viewed or related specifically to leadership development or leadership formation.4 Mary Kathryn Grant, Ph.D., noted in her survey of leadership programs, "The ministry needs a model of leadership development that truly integrates mission, ministry principles and ministry values with clinical, professional and executive competencies."5 A conceptual framework would assist in shaping that model.

What follows is the description of a conceptual framework, originally developed for graduate students in a professional field, which might aid our thinking about competencies as they relate to leadership formation and leadership development.6 (The framework is intended only to aid thinking about the competencies that have already been identified through research; it does not suggest new competencies.)

We are at a critical moment in Catholic health care, when lay leaders may come to the field with seasoned knowledge and skills in their disciplines, but — if they are to lead the ministry into the future — will require a deeper understanding of the tradition of the Catholic healing ministry and the Gospel values that ground it. To assure that adequate formation for leaders is in place, those who create and carry out the programs must be clear about the goals of leadership formation as distinct from leadership development.

Five Dimensions of Leadership

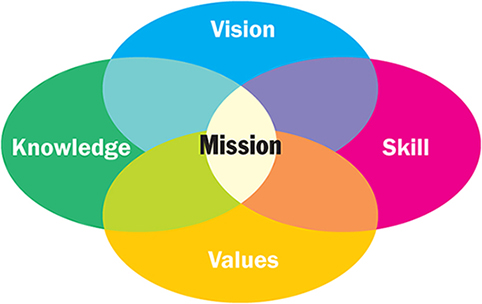

Leadership studies, such as that conducted by CHA, have identified attributes of effective leaders.7 The key elements can generally be clustered in five dimensions: knowledge, skill, values, perspective/vision and purpose/mission. Although these dimensions of leadership are distinct, they are not separate or isolated from each other. They are dynamic, and like the dimensions of a person, they overlap, flow together and influence one another.

They grow as a person advances toward higher levels of achievement, realizing his or her potential in each dimension. Because the dimensions relate to and reinforce each other, growth in one area commonly leads to growth in other areas in a mutually reinforcing dynamic movement.

Progress and growth may lead to increasing levels of mastery, but experience demonstrates that progress is never assured. A person may also experience periods of decline in one or more of the dimensions. Without denying the possibility of decline, the description offered here focuses on positive movement toward fulfillment of one's potential in each of the dimensions: knowledge, skill, values, perspective/vision and purpose/mission.

1. Knowledge

A leader needs both general knowledge and the specialized knowledge of her or his professional field (medicine, accounting, communications, management, etc.). In the leadership role, the person must know about such matters as planning, budgeting and operations. Health care leaders spend years developing this specialized knowledge. When new professionals are hired, or individuals are promoted into leadership positions, the initial area of examination is often aimed at determining whether the candidate possesses the needed content knowledge, with the first consideration centering on indicators of academic success.

Growth in the knowledge dimension leads to a level of mastery, perhaps even movement into the realm of what may be called professional "wisdom."8 While knowledge is essential, our common experience of leaders, even very intelligent leaders, tells us that knowledge in itself is never sufficient for effective leadership.

2. Skill

Every professional must develop a set of skills, often through years of practicing a profession. For example, a neurosurgeon must possess not only a comprehensive knowledge of the brain, but also the finely honed skills needed to perform intricate surgery.

Leaders must also develop a set of skills. Some are specific and technical (creating an effective budget or strategic plan, designing organizational structures to achieve specific goals, leading processes of change); others are more general (assessing the strengths of people, managing one's time and effort). Proficiency in these skills often requires extended periods of training and practice.

The dynamic movement in the dimension of skill is acknowledged when we distinguish a beginner or novice from the person with solid competence and from the person we recognize as a seasoned master. At the higher levels, an individual demonstrates skill in the practice, or art, of leadership.

3. Values

Professions typically express their values in codes of conduct or standards of practice; for instance, in statements like the Hippocratic Oath. Values ground our ethics, and serve as the lens through which we examine whether we should or should not take a particular action. In philosophical and spiritual traditions, values, though they may be called something different, are associated with concepts such as respect, compassion, honesty, integrity and justice. The organizational side of values moves into questions of ethics and collective behavior: how we treat each other and those with whom our organization interacts, as well as whether our decisions are aligned with the values we express.

When regularly practiced, values become part of the character of a person — a part of one's makeup that is essential for any professional, and particularly for someone who seeks to lead others.9 As in the two previous dimensions, knowledge and skills, we recognize that some individuals have moved further along the path of habitual practice of values in their personal and professional lives. We can count on them to be honest in all matters, to keep their word, to treat others with respect.

4. Perspective/Vision

Perspective has two features.10 It refers first to a person's self-understanding, captured in the ancient admonition "know thyself." Contemporary research reinforces the truth contained in this adage by pointing out that accurate self-knowledge is indispensable to effective interaction with others, particularly when one serves in a leadership role.11

The second feature is situational understanding. One must not only know oneself, but also one's situation or environment — what is happening "out there" to which I must respond. Leaders have to deal with daily routine, but must be able to get to the balcony to see the broader context.12

Leaders need an accurate self-understanding, combined with a good sense of their situation, in order to shape a vision for themselves and their organizations. Perspective leads to vision, and a clear vision is critical if a group is to move forward. Hebrew Scriptures put it succinctly, "Without a vision, the people perish." The leader may not create the vision personally, but the leader must name it, making it clear and powerful. Martin Luther King Jr. did not create the vision of racial equality, but he helped change a society in his proclamation, "I have a dream!" An accurate perspective, leading to a clear vision, spoken with conviction, moves people to action and helps shape a new reality. It is an essential dimension of leadership.13

5. Purpose/Mission

The fifth dimension of leadership, which may be called purpose or mission, is associated with words like "spirit," "heart" and "soul." These words point to a level beneath the surface of our knowledge and skill, and beyond our daily work. In this dimension a leader asks, "Why am I doing this? What is my purpose?"14 It is in being clear about this dimension of purpose or mission that the leader finds the strength needed to sustain the effort, to make difficult decisions, and, perhaps most importantly, to inspire others to do the same.15

It is easier to talk about the other dimensions because we can use ordinary language. It is more difficult to talk about our life's purpose, what gives us meaning, what inspires us, what moves us to action. This realm is deeply personal and private. A conversation about one's purpose requires moving away from the language of common experience or professional training toward the language of philosophers and spiritual teachers. For most professionals, this is unfamiliar territory.16

Although we may not be as comfortable in a conversation about personal purpose, we know this dimension makes all the difference. Our sense of purpose gets us through tough times. In the drudgery of routine or the ambiguity of difficult decisions, it reminds us that what we are doing counts for something.

Purpose and mission are at the heart of who we are both personally and organizationally. We look to our heritage and our founding stories to get to our roots — to our original purpose. The mission statements of our organizations invite a deeper awareness of collective purpose. We know team spirit counts and we seek inspiring leaders for our group. The mission brings us together around a common goal to which we can give our assent, our time and our energy.

The dynamic movement here is toward progressively higher levels of purpose. Modern psychology and religious traditions parallel each other in stressing the importance of growth in this area. Both identify the basic drive to meet physical needs (e.g., security and a paycheck), then the needs of our self-identity (e.g., personal autonomy, power and achievement). To find greater fulfillment, we must move beyond ourselves to engagement with others. The spiritual traditions in particular stress the importance of serving others, which finds organizational expression in phrases like "servant leadership."

At an even higher level, some sense a calling to serve a purpose greater than either themselves or those around them, to what is sometimes called a "transcendent" purpose, one that embraces large segments of humanity, creation or, ultimately, whatever one names as the Divine.17 Individuals who operate at this transcendent level become our heroes and saints, inspiring others to find a higher sense of purpose and to take action toward it. When entire groups function at this level of collective purpose, history shows they can change the world around them. We have to look no further than those who founded Catholic health care to see powerful examples of people operating at this level. One study of high performing secular groups puts it this way, "Great groups always believe they are doing something vital, even holy."18

Putting the Dimensions Together

The five dimensions flow together, influencing and reinforcing one another in an ongoing process that is more like the energy fields described by modern physics than the separate objects of classical physics.19 In addition, just as individual leaders manifest these dimensions, organizations also have collective knowledge, skill, perspective, values and purpose, which may be expressed or simply implied in an organization's language and actions.

Much more can be said about how these dimensions are developed to form a person or an organization of excellence, but this outline may help frame the similarities and differences between leadership development and leadership formation.20

Just as there are no hard edges between the dimensions of leadership, there is no clear boundary between leadership development and leadership formation. The goal of both is to aid the leader's growth and effectiveness. Yet each has a distinguishable focus and emphasis and a distinctive approach; and each involves different concepts, language and practices.

Development: Knowledge and Skill

With some exceptions, leadership development is typically focused on the first two dimensions — knowledge and skill — helping the leader advance in areas like planning, finance, operations and human resources. Whether delivered in formal courses of study or short programs, leadership development assists the leader in understanding increasingly sophisticated concepts and ideally offers the leader opportunities to practice the skills needed to apply them effectively — though often participants are left to practice new skills on the job without feedback from instructors. Although some of the more intensive leadership development programs may address the higher dimensions of leadership, such as a leader's self-understanding or goals, most programs focus on knowledge and skills, which are relatively easy and inexpensive to convey.

Formation: Higher Dimensions

Leadership formation, as we have come to understand it in Catholic health care, focuses on the other three dimensions: purpose/mission, vision and values. Formation is designed to bring into sharper focus the ministry's mission, vision and values, and to consider the alignment between these dimensions as they are experienced in the life of the ministry and the life of the leader.21 Formation invites exploration of questions like, "Why are we here? Where are we going? How should we act?" All religious and philosophical traditions remind us that to be fully human, and certainly to be an effective leader, one must move to this deeper level of personal and organizational insight.

For leaders in Catholic health care, a principal goal of formation, as distinct from leadership development, is therefore to help the leader gain greater facility in using the concepts and language needed to reveal these deeper dimensions of values, vision and mission. Only then is it possible to understand how a leader's personal values, vision and mission align with those of the ministry. How does he or she understand Catholic identity and the Catholic heritage? What principles govern his or her actions? Only when a leader is able to apply these concepts and speak about them with ease can they be communicated effectively. A leader who lacks this facility will appear unsure or even phony when talking about these matters, which are vital to the future of Catholic health care as a ministry. But the leader who is as comfortable with the language of mission, vision and values as with the language of finance and operations will exert a powerful influence, uniting people in common purpose to further the ministry and its mission.22

In exploring questions that are fundamental to the ministry, formation invites the leader to address the personal side of the same questions. Why am I here? What is "calling"? What values do I hold? What is important for my future? The invitation to explore these questions is an essential feature of formation because, ultimately, the leader must understand how these questions relate to and align with critical elements of the ministry. Formation programs should deepen leaders' understanding of the ministry's mission, vision and values, while evoking a deeper appreciation of those same dimensions in themselves. Formation encourages self-awareness and understanding of the ministry to grow and deepen together.

Formation: Time and Inner Work

Other differences between leadership development and leadership formation revolve around the manner of presentation and the time needed for successful integration. While both require disciplined study, reflection and practice, whether they take place over years, as in academic degree programs, or over a few days, as in professional workshops, leadership development programs are usually conducted in class settings, using examples and case studies and encouraging workplace application of the learning.

Formation is different. Absorbing values and purpose into the fabric of one's life and learning to lead from a well-integrated mission is an ongoing process, entailing difficult inner work. It evolves slowly, with the initial phase lasting many months if not years. The extended time is an acknowledgement that formation involves much more than acquiring a body of information.

Formation for leadership in the Catholic health care ministry is also different in that it draws heavily from the spiritual traditions generally and the Catholic tradition specifically. It uses the language of these traditions and involves meditation, reflection and journaling, practices that in our culture are not generally part of the experience of a professional or leader. It takes time to understand the language and practices and learn how to use them.

Growth in these areas cannot be achieved by study alone. The process requires a community setting, where issues and questions can be addressed in dialogue with others in a spirit of mutual respect and trust. Formation must therefore be structured to take place within a community of learners who share common experience and who process those experiences together.

Additionally, those who facilitate the formation experience must have special skills. Because formation involves more than imparting information, the typical academic model of teaching and learning does not work. Granted, acquiring information is a necessary component to help participants develop their understanding of the heritage and practices of the Catholic health care ministry. But formation cannot stay at the level of the intellect. It must move to the level of meaning — to the ways in which new understandings affect the life and work of both the leader and the ministry.

Participants need a skilled guide, or guides, to help them process what for many involves unfamiliar concepts and difficult questions. The formation leader must be able to help participants ask deeply personal questions without being intrusive and, without proselytizing, to assist participants, who may come from different religious and philosophical backgrounds, to understand and appreciate the Catholic tradition. This is a tall order. As the number of formation programs already underway contribute to a growing body of experience, they have arrived at the conclusion that this work requires a team of individuals with different skills, perspectives and backgrounds.23

Similarly, the environment and program structure of formation are different from a typical course of instruction. Experience has shown that formation programs are best held away from the workplace, ideally in retreat-type settings that allow participants to unplug from routine responsibilities. It is difficult, if not impossible, to address fundamental questions in an atmosphere filled with reminders of daily tasks waiting to be done. The structure and schedule of the formation program must give space for silence, reflection and dialogue. In fact, the typical packed agenda of a class or business meeting becomes a barrier. Participants in a formation program may receive no agenda beyond starting and ending times to prevent clock watching from becoming a distraction.

No Hard Edges

Although the setting, content, format and facilitation skills needed for leadership formation are different from those employed in leadership development, it bears emphasizing that there are no hard edges or barriers between formation and development. Both are required and they are closely related, though each effort addresses different dimensions of leadership. The needs of different leaders must also be taken into account. For example, a program for new supervisors may focus more directly on the development of knowledge and skills, whereas a formation program for senior leaders may focus almost exclusively on mission, vision and values. It is important to be clear which dimensions are to be addressed and to use the setting, content, format, and facilitation appropriate to nurturing and developing the desired dimensions.

Finally, it is worth noting that the word "formation" can be misleading and can even evoke a negative response. For example, the word might imply an effort to form or shape someone into a person they are not and do not want to become. Worse yet, some might think formation involves indoctrination or religious proselytizing. Properly understood, leadership formation is simply the process of helping the leader appreciate more fully the mission, vision and values of the ministry in which the leader serves and to be able to express them effectively as part of the leader's role. This presumes the leader's personal values, sense of purpose and vision are aligned with those of the ministry. The purpose of formation is not to identify leaders who do not belong in this work. Rather, it is intended to help leaders who want to serve, but who come from a variety of religious and philosophical backgrounds, to deepen their appreciation for the Catholic ministry in which they play such an important role.

Nurturing What Is Within

Ultimately, formation is not a process of imposing something foreign from without, but one of illuminating and nurturing dimensions already within the leader. When all elements of an effective formation program come together, formation brings into the leader's life and work a broader perspective, a deeper sense of purpose, and a greater energy and enthusiasm for life and for serving as a leader in Catholic ministry.

At this time in the history of Catholic health care the effective formation of our leaders is essential, not optional. While there is growing appreciation of that fact, there is work to be done in understanding the indispensable elements of formation and how best to deliver them. This much is certain: as we continue the journey toward fully lay leadership across our ministries, the future of Catholic health care depends on our ability to help form committed women and men who have a deep appreciation for traditional Catholic health care and who have integrated its mission and values into their lives and work.

NOTES

- In 2002, Mary Kathryn Grant wrote a white paper on "leadership development" summarizing more than a decade of efforts in the field. Grant, "Building on Past Success," Health Progress 83, no. 3 (May-June 2002): 30-35, 64. Six years later, Health Progress devoted a special section to "leadership formation" in its March-April 2008 issue (vol. 89, no. 2).

- Dennis Winschel offers important insights into the key features of the formation and how they differ from the features of a typical career path in "Formation Path in the Workplace: How Does It Work?" Health Progress 89, no. 2 (March-April 2008): 20-22.

- John Larrere and David McClelland, "Leadership for the Catholic Healing Ministry," Health Progress 75, no. 5 (June 1994): 28-33, 50.

- The CHA study proposed such a framework for the competencies it identified, but for reasons that are not clear, it has not found widespread use beyond the initial CHA follow-up activity.

- Grant, 64.

- John Mudd, "Beyond Rationalism: Performance-Referenced Legal Education," Journal of Legal Education 36 (1986): 189.

- Stephen Covey offers a helpful summary of common theories of leadership in The Eighth Habit (New York: Free Press, 2004), 352-358.

- Donald Shön points out that professionals move to this level of understanding, not simply by study, but by engaging with real situations in a process of "reflection-in-action." See Shön, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

- For example, James Kouzes and Barry Posner have found from their research, extending over many years and involving different cultures, that honesty is the single attribute most consistently identified as essential for effective leadership. Kouzes and Posner, Credibility (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993), 14.

- I have described this dimension in greater detail in "The Place of Perspective in Law and Legal Education," Gonzaga Law Review 26 (1990-1991): 277.

- For example, the research of Daniel Goleman and his colleagues identify self-knowledge as foundational for effective leadership. Primal Leadership (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 2002), 109-112. Describing the leadership characteristics that have sustained the Jesuits for 450 years, Chris Lowney concludes, "All leadership begins with self-leadership, and self-leadership begins with knowing oneself." Lowney, Heroic Leadership (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2003), 98.

- Ronald Heifetz uses the metaphor of "getting to the balcony" to describe this essential ability of effective leaders, who must simultaneously be in the action and yet above it. Heifetz, Leadership Without Easy Answers (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994), 252-263.

- Kouzes and Posner put it this way: "Exemplary leaders are forward-looking. They are able to envision the future, to gaze across the horizon of time and imagine the greater opportunities to come. They see something out ahead, vague as it might appear from a distance, and they imagine that extraordinary feats are possible and that the ordinary could be transformed into something noble. They are able to develop an ideal and unique image of the future for the common good." Kouzes and Posner, The Leadership Challenge (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 4th ed. 2007), 105 (emphasis in the original).

- Dag Hammarskjold's famous diary entry captures this dimension. "I don't know who — or what — put the question, I don't know when it was put. I don't even remember answering. But at some moment I did answer yes to someone — or something — and from that hour I was certain that existence is meaningful and that, therefore, my life, in self-surrender, had a goal." Hammarskjold, Markings (London: Faber and Faber, 1964), 85.

- "Leonard Doohan writes that once one gives attention to purpose there is a shift." Leadership is no longer a matter of skills and accomplishments; rather it focuses on the ultimate meaning of life, it deals with destiny and one's role in the universe." Doohan, Spiritual Leadership (Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 2007), 37. Ronald Heifetz puts it this way, "[T]he practice of leadership requires, perhaps first and foremost, a sense of purpose — the capacity to find the values that make risk-taking meaningful." See also Heifetz, 274.

- Parker Palmer describes the inner journey of the leader to be essential because a leader has the power to project his or her inner shadow or light on others. Palmer, "Leading From Within: Out of the Shadow, Into the Light," in Spirit at Work, Jay Conger, ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994), 19-40.

- For a visual summary of this dynamic movement in the work of Maslow, Piaget and others, see Ken Wilber, The Integral Vision (Boston: Shambhala, 2007), 112-113.

- Warren Bennis and Patricia Biederman, Organizing Genius (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1997), 204.

- Margaret Wheatley provides an elegant description of how our understanding of organizations and leadership must catch up with our understanding of the physical world in seeing reality, not as separate objects, but as elements constantly relating to each other. Margaret Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science (San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler, 1999, 2nd ed.).

- The dimensions may also be viewed dynamically as part of the process of human growth — how we experience growth (or decline) individually and collectively in our organizations and in society. Bernard Lonergan offers this dynamic approach as part of his philosophy and theology. For example, see Lonergan, Method in Theology (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), chapter 2.

- From his perspective as a former CEO, Bill George describes this alignment as essential. "To find your purpose, you must first understand yourself, your passions, and your underlying motivations. Then you must seek an environment that offers a fit between the organization's purpose and your own." George, Authentic Leadership (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003), 19.

- I develop this theme in "From CEO to Mission Leader" Health Progress 86, no. 5 (September-October 2005): 25-27.

- While the use of teams is commonly reported by colleagues doing this work, the programs with which I am personally familiar that have adopted this approach are the three-year program for senior executives conducted by the Ministry Leadership Center, Ascension Health's two-year program, and the two-year program by Providence Health & Services.

Copyright © 2009 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.