BY: FR. CHARLES E. BOUCHARD, OP, S.T.D.

Ascension Health's Program Aims to Enhance Understanding and Commitment to the Ministry

Fr. Bouchard is vice president, theological education, Ascension Health, St. Louis.

Catholic health care systems now realize that in order to maintain a vital ministry into the future, they have to educate, develop, and form key leaders in the theology and spirituality that inspired previous generations. Formation programs have existed for some time at a number of levels in many different systems, but formation for governance boards is new and evolving.

In 2007, the Board of Ascension Health commissioned a special task force on board development and formation. Board members had observed the impact of leadership formation programs at other levels and wanted to ensure a consistent approach to formation of individual ministry boards across the system.

The task force recommended a board formation program that would strengthen board members' awareness of the theological foundations of the ministry, contribute to greater uniformity in governance across the system and eventually affect the way we recruit new board members and assess board work. Board formation activities began in July 2008 with pilot sites at five ministries, each of which is a system in itself, including at least one acute care hospital, plus long-term care and some specialty services. At some ministries, formation activities are limited to the system board; at others, they include boards of subsidiary entities.

This article is an early progress report that describes what we mean by "formation," why we think it is important, and some successes and challenges we have experienced.

What is formation?

This word is familiar to anyone who has been in religious life or the seminary. Formation is the period of intellectual, spiritual, human and ministerial development that takes place after a candidate enters the seminary or religious life but before assuming ministerial duties. Ascension Health's formation programs are not intended to replicate seminary or religious formation, and debate is ongoing about whether formation is the correct word. Priests and religious who had negative formation experiences see it as inappropriate. They are concerned it suggests passivity and indoctrination. Others worry that formation will be seen as proselytizing or conversion. Even those whose experience was not negative may object that, as adults, they are "already formed," so education or development would more accurately describe what takes place in these programs.

In Ascension Health we have decided to stay with "formation" because we do not feel that any other term quite conveys the multi-faceted dimensions of our programs. Our formation efforts are built on the conviction that persons are essentially spiritual and that everyone has a spirituality, or at least a spiritual awareness. The point of formation is not just to transmit knowledge or inculcate a technique or a practice but to deepen understanding of and commitment to the ministry. We do not want to impose spirituality; rather, we want to awaken the spiritual sensitivity that is already there.

Ascension Health has multiple formation programs for executives, associates, middle managers and physicians. These programs started independently of one another and differ in format. In an effort to achieve greater uniformity in content and outcomes across all programs we have adopted a common definition of formation:

"'Formation' is a transformative process, rooted in theology and spirituality, that connects us more deeply with God, creation and others.

Through self-reflection it opens us to God's action so that we derive meaning from the work we do, grow in awareness of our gifts, see our work as vocation and build a communal commitment to the ministry of health care."

The key elements are transformation (a change in the participant's vision, motivations or understanding); self-reflection; meaning; vocation; and community. Community is particularly important because even though formation begins with its effect on individual participants, its ultimate purpose is to sustain a dynamic mission community that will lead our ministries. It was the strength of religious communities, after all, that enabled these ministries in the first place.

Why undertake formation?

Kenneth Homan, system ethicist at Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth Health System, Lenexa, Kan., provides an excellent rationale for board formation:

"Governance must be formed in the 'why' of the mission if it is to be an effective force in the culture of Catholic health care. The 'why' of mission is the transcendent purpose, the greater good of God's love and God's healing presence that motivates and amplifies Catholic health care culture. When trustees fail to understand the 'why' of mission — their institutions' greater and more durable good — lesser and more proximate goods will drive the engine of Catholic health care."1

Another way of saying this is that if health care is to survive as a ministry of the church, someone has to know some theology.

Of course Catholic health care has ethicists, mission executives and other theological experts, but we must expose a broader range of leaders and associates to the tradition that shaped our sponsored ministries. In ways appropriate to their aptitude and responsibility, each person involved in the ministry must have at least a basic understanding of the "why" of the mission. Each one must understand how he or she contributes to the healing ministry of Jesus, to the common good of health care and, by extension, to the Reign of God.2

For boards this means acquiring a basic theological vocabulary and fluency that enables them to discuss the issues they face from the perspective of church, ministry, Christology and Scripture, just as they now discuss them from the perspective of finance, planning and competitive environment. In my own service as a board member, I have had to learn about DSH (Medicare Disproportionate Share) payments, Stark laws, and cost-to-charge ratios. Are words like "incarnation," "church," "ministry," "PJP" (public juridic person) and "magisterium" not equally important to those involved in Catholic health care governance?

Ministry boards exercise the same fiduciary responsibilities for finance, mission and strategy as their counterparts at publicly held companies. Our hospitals provide traditional board development activities that focus on what boards do and how they function, just as public boards do.

But Catholic health care is also a ministry. Its mission touches on the transcendent, and this makes it different from a publicly held company whose primary purpose is profit. This difference means that board members need more than the usual governance skills to be effective. They also need the right motivation and certain qualities of character, or virtues.3 Board formation focuses primarily on identity and meaning — who board members are and how they understand their role, both individually and as a group. I have found Ken Wilber's approach to human development and the four quadrants of his "integral model" of formation to be useful in conceptualizing this.

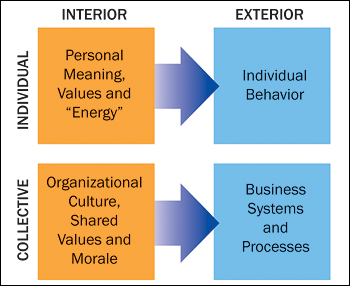

In Wilber's model the right side of the quadrant is concerned with empiric observation — what does it do? The left side of the quadrant focuses on interpretation — what does it mean? "Wilber contends that modern times evidence a pathological separation from healthy evolution due to a near-complete focus on the right sides, with the denial of the left side as having no meaning being a fundamental cause of society's malaise."4

Board formation focuses on the left, or "meaning," side of the quadrant, both individually and corporately. It provides an opportunity for individuals to become more aware of their own spiritual lives and to deepen that spirituality. The self-reflection and interior transformation that is part of formation leads to the right side of the grid, enabling us to create "model communities" that can carry out the mission more effectively.

Another reason for board formation is to clarify and strengthen the role of the board relative to the role of sponsors, especially as sponsorship structures evolve. In some cases new public juridic persons have more or less combined governance and sponsorship functions at the system level,5 but in most systems there is still a "sponsor's council" or other structure that enables several communities to exercise a joint sponsorship role that is distinct from governance.6

Continuing evolution of sponsorship means that we must take care to evaluate and clarify the duties and responsibilities of the board.

Finally, formation activities should contribute to something like what Richard Chait and his colleagues describe as "generative governance."7 Rather than merely "taking care" of their charge (fiduciary) or planning for its future (strategic), the best governance should also involve creativity. This is particularly important at a time when health care, society and the church are undergoing massive transformation. Just as we have imagined new forms of health care that led to laparoscopic surgery and telemedicine, so we must also ask, "How can we imagine a new way for the church to be present in the world through health care?"

What do boards need to learn?

Even though formation focuses on personal qualities and spirituality, it also involves the acquisition and integration of a body of knowledge. We have packaged this content in the following series of seminars or modules, each of which involves a brief pre-read, a presentation and a discussion.

What is Formation?

- Health Care: Business or Ministry?

- Health Care and the Church

- Scriptural Roots of the Health Care Ministry

- What Boards Need to Know About Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, Governance and about Catholic Social Teaching

- Virtuous Leadership: Spirituality for Governance

These seminars can be done one at a time during the course of regularly scheduled board meetings, or a number of them can be combined in a board retreat. In addition, we believe that in order to function effectively, board members need to know about 20 theological words or concepts. We are developing brief definitions of these words in a flashcard format that can be presented in the context of a seminar or in a brief session lasting as little as 10 minutes.8

Finally, we plan to offer periodic webinars for board members across the system on topical issues (e.g., health care reform and Catholic social teaching).

The formation process should enable board members to acquire certain competencies including the ability to:

- Articulate their own spirituality.

- Articulate how health care is a ministry of the church and how it differs from other kinds of church ministry.

- Cite the main Scriptural roots of the ministry of health care.

- Use key theological words confidently in board discussions.

- Arrive at policy decisions that take explicit account of mission values.

Challenges to Formation

My first year of board formation work has been encouraging. The most satisfying moments are those when board members realize that they are not just "helping the sisters with their hospital," but assuming real fiduciary and spiritual responsibility in their own right. Still, there are a number of challenges.

Diversity: The first anxiety about board formation arises from the tension between diversity and singleness of purpose. CEOs and board chairs rightly value the diversity of their boards and do not want to do anything that will alienate or isolate board members who do not share Catholic faith convictions. They also know that board members serve for different reasons. Some serve as an expression of their Catholic faith, others because they value health care as a community good, still others for political or personal reasons.

Our approach to formation is theological and rooted in the Catholic tradition. This is important for two reasons. It serves our Catholic board members who are well-educated generally but lack a mature adult understanding of their faith. They welcome the opportunity to delve more deeply into questions about church authority, religious charisms and social morality.

In addition, board members who are not Catholic or Christian welcome the opportunity to gain a fuller understanding of why we are in the business of health care and what has motivated the church to invest so heavily in institutional ministries. We try to draw parallels between the Catholic tradition and other traditions whenever possible. For instance, I recently spoke to one of our boards about the similarities between Catholic social teaching and the Jewish concept of tzedakah (a combination of justice and charity). A Jewish board member who was active in community development said, "I'm right with you. This parallels my own tradition perfectly."9

It is possible that as we move toward requiring participation in formation activities for board membership, we may lose a few prospects who are not interested in exploring personal spirituality. This is not a bad thing. It simply says that health ministry governance is a specialized call and is not for everyone.

Time: Board members are volunteers. They meet periodically, their meeting time is short and agendas are full. These limitations require flexibility and a combination of short sessions, longer sessions and occasional board retreats that allow for more reflection. I have found that after a period of time, board members begin to see that these sessions are personally enriching and helpful to their work, so they are willing to make time for them within board meetings. Growing numbers of CEOs and other senior leaders who have completed a formation process are invaluable allies who can make the case for board formation from personal experience.

Symbol, Ritual and Prayer: This is a sensitive issue because we are trying to balance respect for a diverse board membership with authentic expression of who we are as a Catholic ministry. Liturgy, prayer and personal acts of devotion are an important part of our tradition; they are probably the most important formative experiences of the religious communities who founded our ministries. The rhythm of Eucharist and common prayer shaped these pioneers personally and corporately.

Health care board meetings typically begin with a non-denominational or secular reflection. This can be appropriate, especially when some board members are not Catholic or Christian. Yet we must ask whether board members can fully assume their responsibility for ministry governance if they have not had some exposure to specifically religious and even Catholic forms of prayer. There are a number of prayer forms that are familiar to Catholics that can be adapted for a wider audience. Some examples follow:

- Every major religious tradition has some kind of contemplative or meditative activity. A combination of meditative instrumental music, a carefully chosen and well-read passage from Scripture or some other source, followed by a significant period of silent mediation (e.g., at least 10 minutes) and a concluding shared prayer could provide a powerful common prayer experience.

- Liturgy of the Hours provides a ritual structure, including Hebrew psalms, periods of silence, Scripture or other readings for morning, midday or evening.

- Blessings and commisionings are a good way to mark new memberships and other transitions with prayer, music and gesture.

- Eucharist is the heart of Catholic liturgical and spiritual life. It cannot serve every purpose, but especially in situations where a majority of board members are Catholic, it should be celebrated at least occasionally. Those who are not Catholic can be warmly invited to attend.

These prayer experiences are helpful to individual members and also can improve communication among board members. William Murray, CEO of the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth Health System, said, "Sharing spirituality really breaks down barriers and enables board members to raise hard questions with one another."

Sustainability: Because board membership is constantly changing, board formation is not "once and for all." In order to be effective, formation has to be ongoing. Sustaining quality board formation activities without resorting to videos or booklets that quickly get shelved requires a long-term plan. Local leadership, especially the CEO, the board chairman and the mission integration officer, must be active participants.

Assessment: As a result of the formation process the big question is, "Did anything change?" After a period of formational activities, do boards and board members think, act, deliberate or make decisions differently than they did before? Do they feel differently about exercising their roles in governance? Has their understanding of their own faith or spirituality changed? Are their relationships with one another or with the senior staff different? We are just beginning to develop a qualitative assessment plan, but other systems have already developed some very helpful tools.10

A Final Note

The current moment in ministry leadership is unprecedented. At no time in history has the leadership of such a massive ministerial organization undergone such dramatic change in such a short time. We have learned a great deal about formation for leadership and governance, but we are still writing the book, and our efforts need sustained attention.

NOTES

- Kenneth Homan, Ph.D., "Formation and Governance: Catholic Organizations Should Institute Theological and Spiritual Formation Programs for Their Trustees." Health Progress 85, no. 5 (September-October 2004), 23-29.

- This point is too complex to explore fully here, but it is important to note that in public life, health care serves the common good; theologically, however, the Catholic tradition sees the common good as a glimpse or partial realization of the Reign of God, which will be characterized by full justice and equity.

- The idea of virtues for leadership and governance needs fuller development, especially given the prominent place of virtue in Catholic ethics. See Helen Alford and Michael Naughton's fine discussion of virtue in Managing As If Faith Mattered (Notre Dame, 2001), 70-98.

- "Ken Wilber," http://en.wikipedia.org, Aug. 11, 2009. His highly eclectic approach is based on Asian philosophy and spirituality as well as on the work of experts in human and moral development such as Erik Erikson, James Fowler, Lawrence Kohlberg and Abraham Maslow. For a fuller description of Wilber's approach, see his Integral Spirituality: A Startling New Role for Religion in the Modern and Postmodern World (Boston, Integral Press, 2006).

- Catholic Health Initiatives has a single board that includes both "sponsorship trustees" and "stewardship trustees."

- Ascension Health has "sponsorship of the whole," which is the responsibility of a Sponsors' Council made up of representatives from founding communities and two lay persons. Catholic Healthcare West has corporate members who represent each of the sponsoring congregations and appoint the board of directors. Catholic Health East is jointly sponsored by several religious communities and a public juridic person.

- Richard Chait, William Ryan and Barbara Taylor, Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley and Sons, 2005).

- Some of the most important words board members need to know are: church, ministry, magisterium, bishop, salvation, common good, Jesus Christ, eschatology, sponsorship, natural law, Gospel, Catholic social teaching, justice, virtue, vocation, intrinsic evil, cooperation, principle of double effect, grace, sacrament, solidarity and subsidiarity.

- See Rabbi Jonathan Sacks' discussion of this concept in The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash of Civilizations (New York: Continuum, 2002). See especially chapter 3, "Compassion: The Idea of Tzedakah."

- For instance, Brian O'Toole and Lynette Ballard of Sisters of Mercy Health System in St. Louis have developed a board formation values inventory with a pre-test and post-test that enables them to measure the success of formation efforts.

Copyright © 2009 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.