BY: KAREN LOVE and ELIA FEMIA, PhD

Mary entered Mrs. P's bedroom and gently placed a hand on her arm, saying "Good morning, Mrs. P, it's Mary.1 Let me warm up those knees of yours before you get up." Mary pulled up the side of the bedclothes, keeping the rest of Mrs. P's body covered, and tenderly placed both of her hands around one knee at a time. It was clear from the smile on Mrs. P's face how good the warmth from Mary's hands felt on her 89-year-old knees. After a couple of minutes of comforting touch on each knee as Mary softly described what they would do together that morning, Mrs. P was ready to get up.

Mary entered Mrs. P's bedroom and gently placed a hand on her arm, saying "Good morning, Mrs. P, it's Mary.1 Let me warm up those knees of yours before you get up." Mary pulled up the side of the bedclothes, keeping the rest of Mrs. P's body covered, and tenderly placed both of her hands around one knee at a time. It was clear from the smile on Mrs. P's face how good the warmth from Mary's hands felt on her 89-year-old knees. After a couple of minutes of comforting touch on each knee as Mary softly described what they would do together that morning, Mrs. P was ready to get up.

What a contrast to the unpleasant mornings they used to have. Trained in caring for people with Alzheimer's, Mary had experienced the progression of Mrs. P's disease over the past four years, and she knew many appropriate techniques to try, such as speaking directly to a client at his or her eye level. Even with those, getting Mrs. P out of bed each morning became increasingly difficult, leaving them both exhausted and frustrated.

Fortunately, during one of the thrice-yearly training sessions Mary's home care agency provided, Mary learned about using comforting touch as a tool. She tried it with Mrs. P, and it became a pleasant part of their morning routine. The gentle touch Mary provided took only a short time, five minutes or so, and it amazed her that something so easy to do could make such a difference to them both.

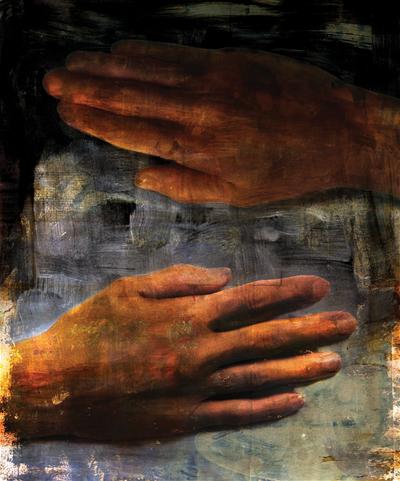

Comforting touch is an intentional, physical way to convey compassion and care to another person and to create an emotional connection. Human touch can provide comfort and support and make a person feel more relaxed. It also can help relieve pain and other physical discomfort. Touch can be as simple as a hug or a gentle squeeze on the shoulder, or it can involve a more systematic process of gently placing warm, closed hands on various parts of the body.

Since ancient times and around the world, touch has been used to deliver comfort and healing. Touch is the most basic element of human development; it starts in the womb and becomes the first sensory system to become functional — before sight, smell, taste and hearing. Touch is the first experience of a newborn baby upon entering the world. Mothers instinctively use touch as a form of communication, to soothe and calm a child in discomfort. Touching an injured area is generally the first thing people do when hurt; it's almost automatic. As a matter of everyday language, the phrase "that was so touching" expresses being emotionally moved.

The body's physiological response to comforting, caring touch starts with the brain's release of oxytocin and the engagement of the limbic system2 that, in turn, stimulates the body's autonomic, endocrine and immune systems. Physically, this can stimulate lymph flow that boosts the body's immune system, improves circulation, reduces muscle cramping and provides temporary relief from pain.3 Emotionally, the physiological response can trigger feelings of being cared about, of emotional closeness and connection, trust, relaxation and calm.

Comforting touch becomes especially beneficial for people who have dementia. The neural systems underlying emotional processing and feelings continue to be functional after other cognitive abilities decline,4 and research shows the good feelings triggered by the comforting touch persist long after the actual event. Also, for someone living with dementia, understanding verbal communication can become cognitively exhausting. A gentle, caring squeeze of the hand can convey emotional support without words. Moreover, as the person's ability to verbally communicate lessens as their dementia progresses, a comforting touch can help give them a means to express and reciprocate their emotions.

Research methodologies to measure the nuances of touch have yet to catch up with practices. There is ample anecdotal evidence, but the amount of high quality, experimental research to establish empirical evidence regarding touch interventions for people living with dementia is limited.5

In 2013, the U.S. Administration on Aging funded a project directed by Elia Femia of Pennsylvania State University and Karen Love, founder of CCAL Advancing Person-Centered Living, a nonprofit national advocacy and education organization, to study the effects of training home care aides on touch techniques and evaluating the outcomes.6 The findings were positive; aides reported that 50 to 70 percent of their clients who were living with dementia experienced increased happiness, calm and sleep. To a slightly lesser extent, they also reported that their clients functioned better (that is, could walk better, or their range of motion improved), were less resistant, less angry and more cooperative. Only a very small proportion of aides (5 percent to 10 percent) reported a negative response (such as wanting the aide to stop) or no difference in emotional or physical benefits.

The study also found that the benefits of using comforting touch extended to the aides themselves. After receiving training in touch techniques, aides reported being able to provide better care and feeling a higher satisfaction with their care role. It also helped them feel closer to their clients, which is a key factor in home care aides' tenure and satisfaction with the job. Nine out of 10 aides (90 percent) used the techniques consistently over the 8-month period of the project, and more than 90 percent reported they would continue to use these skills in the future.

One aide said, "[My client] loves it! Her mood is much happier, and she glows. Before, she seemed bored and showed no interest in anything. Now, [my client] looks forward to receiving touch at each visit. This is also a good experience for me. I, too, am glowing!"

Engaging touch and the other senses can be extremely valuable techniques while caring for people living with dementia. They lose the ability to self-engage and, as a result, can spend long periods of time with nothing to do, which can cause boredom, frustration and anxiety. Engaging the senses can provide interesting and stimulating things for them to do: A former artist finds pleasure creating art with her hands by attaching cloth bands to small posts on a geoboard. Organic play clay can be lots of fun for people who like to dig their fingers into something satisfying.

Physically touching things themselves also can be relaxing and feel good for the elderly. A daughter whose mother has Alzheimer's describes how her mother could sit for hours, gently stroking the family's small dog. The look of contentment on her mother's face warmed the daughter's heart.

Another individual, Mrs. A, used to love to knit and crochet small blankets. She lost the ability to do this when her dementia advanced, but watching her mother one day, Mrs. A's daughter realized how much her mother enjoyed running her fingers across the small, knitted blanket covering her lap. The tactile experience appeared to comfort her. The feel of the knitted rows likely triggered long-ago pleasant memories of handling knitting projects. Thereafter, the daughter made sure her mother had a knitted blanket nearby to run her fingers across.

It is not unusual for women with advanced dementia to enjoy holding a baby doll or stuffed animal. For women who raised babies, the sensation can spark warm maternal associations. Thus, knowing a person's background and history can help identify things that he or she may find pleasant to the touch. One son, for example, discovered that walking barefoot in the sand at the beach brought joy to his father as his dementia progressed. Similarly, a person who loved to garden may especially like the feel of touching and digging in potting soil, or someone who once enjoyed making bread now may like the sensation of kneading bread dough.

To be sure, activities may need to be adjusted with individuals who have dementia. Instead of making bread out of the dough they are kneading (and perhaps placing on unclean surfaces), for example, let them enjoy the activity and then unobtrusively substitute that dough with another batch already prepared and ready for the oven. The smell of baking bread is a great stimulant to other senses.

KAREN LOVE is founder of CCAL Advancing Person-Centered Living (www.ccal.org) and ELIA FEMIA is a research associate at Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pa. They are co-founders of FIT Kits®, dementia engagement products and resources to help improve the quality of life for people living with dementia and their care partners (www.fitkits.org).

NOTES

- Names have been changed for privacy.

- Ruth F. Craven, Joie Whitney and Diana Lynn Woods, "The Effect of Therapeutic Touch on Behavioral Symptoms of Persons with Dementia," Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 11, no. 1 (January 2005): 66-74.

- Mitchell L. Elkiss, John A. Jerome, "Touch — More Than a Basic Science," Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 112 (August 2012): 514-17.

- Edmarie Guzman-Velez, Justin S. Feinstein and Daniel Tranel, "Feelings Without Memory in Alzheimer's Disease," Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 27, no. 3 (2014): 117-29.

- Niels Viggo Hansen, Torben Jorgensen and Lisbeth Ortenblad, "Insufficient Evidence to Draw Conclusions about the Possibility That Massage and Touch Interventions Are Effective for Dementia or Associated Problems," The Cochrane Library, published online 10.8.2008; http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD004989/DEMENTIA_insufficient-evidence-to-draw-conclusions-about-the-possibility-that-massage-and-touch-interventions-are-effective-for-dementia-or-associated-problems.

- Elia E. Femia, Evaluation of the Therapeutic Engagement and Compassionate Touch (TECT) Project (2013). Final report prepared for the D.C. Office on Aging and Home Care Partners under an Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration Grant to States funded by the U.S. Administration on Aging.

THERAPEUTIC EFFECTS OF TOUCH

Caring, comforting touch is easy, safe and rewarding to do. Plus, the techniques are intuitive for many and simple and easy to learn for others.

It's important to note that not everyone likes to be touched. Some people don't like the tactile sensation of being touched; some are uncomfortable about being touched by someone they don't know. If you aren't certain about someone's comfort level regarding touch, ask. If the individual has advanced dementia and cannot respond to a question, gently touch them and carefully observe their body's response. Pulling back, widening eyes and flinching are some signs that they are not comfortable with being touched. In these cases, a warm smile can convey your care.

Comforting touch techniques are simple to learn and easy to use. The more practice you get, the better your skills become. Here are a few techniques to get you started:

- Think of your hands as gentle instruments that can deliver kindness and care. This mindset helps transform your touch to an act of caring from the heart

- Lightly place both closed, slightly cupped hands on various clothed parts of a person's body — shoulders, arm, back, neck, hands, ankles — for five seconds or more so that the person can feel the warmth from your hands.

- The amount of time needed to apply touch can be short or long, depending on the amount of time you have available. It can last for a minute or so to 30 minutes or longer — it's your choice. Even if you don't have any time, a gentle touch on a person's shoulder delivered with a smile shows that you care and makes the person — and you — feel good.

|

Copyright © 2014 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.