BY: RON HAMEL, Ph.D.

Surveys of Ethicists and Mission Leaders Indicate Concerns about the Future of Ethics in the Catholic Health Ministry

Dr. Hamel is senior director, ethics, Catholic Health Association, St. Louis.

What is the future of ethics in Catholic health care? This may seem to be an odd question. Many assume that ethics and Catholic health care are natural partners; where Catholic health care exists, ethics is present. This assumption, however, is not necessarily valid, and could lead to taking ethics for granted, which in turn could lead to lack of attention and neglect. For the most part, ethics does not just happen. Just as a mission-permeated health care culture is built on commitment and care, ethics requires deliberateness and nourishing.

So why question the future of ethics in Catholic health care? Some years ago, theologian and ethicist John Glaser, S.T.D., observed that there are "no ethics-free zones"; that is, virtually everything that we do in Catholic health care (and elsewhere) has an ethical dimension.1 Whenever decisions are made or actions performed that affect human dignity and well-being, ethics has a role. This suggests that ethics is an ever-present reality in the day-to-day operations of Catholic health care, not just at the bedside, but throughout the organization.

Given that ethics is so central, so critical to the organization's identity and integrity,2 is Catholic health care according ethics the explicit attention it deserves in daily decision-making? Equally important, are ministry leaders sufficiently attending to the quality of ethics in our organizations today and into the future?

Although ethics, in a sense, is the responsibility of all, some in our organizations are charged with this responsibility in a particular way — ethics committees; mission leaders who, in addition to doing mission, also are expected to fill the ethics role; and professional ethicists.

The latter are a relatively recent phenomenon in Catholic health care, appearing initially as "clinical ethicists" in hospitals. As Catholic hospitals and other health care facilities joined together to form health care systems, ethicists began to work at the system level. Some ethicists serve in both capacities. In comparison to mission leaders, professional ethicists who work directly in Catholic health care are relatively few in number — about 55.3

Interestingly, and of some concern, almost nothing has been written about the role and expectations of ethicists in Catholic health care, nor does there appear to be any clearly defined picture of their role, or of the ethics function in those places where it is carried out by mission leaders.

In response to this lack of information, the Catholic Health Association in fall 2008 conducted two ethics surveys that sought information from ethicists in Catholic health care, and mission leaders who carry out the ethics function.4 The purpose of the surveys, published under the title CHA Ethics Survey, 2008, was not only to get a better picture of those who do ethics in Catholic health care (excluding ethics committees), but also to obtain the kind of data that might be helpful for hiring and recruiting, standardizing qualifications and competencies, providing educational and development programs, doing strategic planning, and planning for the future.

Some of the following information obtained from the surveys raises significant concerns for the future of the ethics role and the future of ethics in Catholic health care.

SURVEY OVERVIEW

CHA invited individuals from two groups to participate in almost identical online surveys. The first group consisted of professional ethicists and included system (national and regional) and facility ethicists, as well as ethicists from several Catholic bioethics centers and academic institutions who contribute significantly to Catholic health care in a variety of ways. This group totaled 79. The overall response rate was 62 percent, though not all respondents answered every question. Unfortunately, technical glitches prevented some from accessing or completing the online survey, and not all respondents answered every question.

The second group consisted of mission leaders who also carry out the ethics function within their organizations. Because CHA did not know specifically who these individuals were, an e-mail was sent to all system and facility mission leaders inviting them to complete the survey only if, as part of their responsibilities, they also filled the ethics function. Although we believe that the actual number of mission leaders who cover ethics within their organizations is considerably larger, 179 replied to the survey. Here, too, technical glitches prevented some from accessing or completing the online survey.

What follows is an overview of the results of each survey, with some emphasis on the survey results from the professional ethicists. The overview is divided into four parts:5

- The people "doing ethics" in our organizations

- What they do — their roles, responsibilities, activities and concerns

- Their perceptions about ethics in their organizations

- Considerations for the future

Who is Responsible for Ethics?

1. Gender, Religious Affiliation, and Educational Preparation

Among the professional ethicists, the majority is male (63.3 percent), lay (77.8 percent), Roman Catholic (77.8 percent), and hold a Ph.D. or S.T.D. (73.5 percent). Of those holding these terminal degrees, 10 respondents have their degree in moral theology, 10 in health care ethics, seven in philosophy, two in historical theology, and one each in canon law, education, religion, philosophy of medicine, and bioethics. Three respondents hold an M.D.; one holds a J.D.

Each of these disciplines undoubtedly makes its particular contributions to ethics in the ministry. However, if there is an assumption and/or a desire that ethicists in Catholic health care be steeped in the Catholic moral tradition at minimum and, ideally, be able to bring a theological lens to their work and to the issues they address, it is fair to note that, according to the survey, those who hold a doctorate in a theological discipline are in the minority. Quite likely, most of these are from an older generation of ethicists who were seminary trained. (Some ethicists whose Ph.D. is not in a theological discipline do hold a master's degree in theology.)

The profile of mission leaders who do ethics in their organizations is quite different from that of the professional ethicists. They are predominantly female (72.1 percent) and almost evenly split between religious and lay (44.9 percent religious and 42.7 percent lay). They too are predominantly Catholic (88.2 percent). The vast majority (80.4 percent) hold a master's degree; 15.1 percent have a Ph.D.

When asked whether they had formal training in ethics, a solid majority (60.9 percent) reported they did, while a significant minority (39.1 percent) said they did not. When asked about formal training in health care ethics, 76.1 percent responded in the affirmative. Formal training was construed to be assorted courses for 48 percent; workshops/conferences for 59.2 percent. A much smaller number, 8.4 percent, indicated that formal training consisted of a summer workshop. Only 10.1 percent said they had received a certificate in ethics or health care ethics, and only 5.6 percent reported having a master's in these areas. In essence, only 15.7 percent of those who said they had formal training actually do, strictly speaking, meaning they hold either a certificate or a degree in ethics or health care ethics.

What this data suggests is that ethics in Catholic health care is often done by individuals who have no formal training, whether in health care ethics, the broader field of ethics, or Catholic moral theology. This is not to fault those individuals who have been asked by leadership to shoulder this responsibility. Nor is it meant to diminish their commitment and their hard work or to ignore the financial benefit of asking one person to wear several hats. But it does raise questions about how well the role of ethics is understood within our organizations and how well it is valued, especially by leadership. Mission and ethics are not the same. What qualifies an individual to do mission may not qualify him or her to do ethics, and vice-versa.

2. Location

The "location" of professional ethicists in Catholic health care has significant implications for desired qualifications and competencies of new and future ethicists. Survey results show that a majority of professional ethicists in Catholic health care function as system ethicists (63.6 percent), though some of these (those employed by a regional system) are likely to also have clinical responsibilities. Few acute care facilities and, to our knowledge, no long-term care facilities have a full-time professional ethicist.

Unlike professional ethicists, mission leaders who have an ethics role in their organizations are almost evenly divided between acute care facilities (40.9 percent) and health care systems (41.5 percent), whether regional (27.7 percent) or national (13.8 percent). Just 9.4 percent of respondents work in long-term care facilities.

This difference in location might account for other differences between the two groups, such as professional preparation, roles and responsibilities, competencies, interests, professional development and professional needs.

3. Compensation

The CHA ethics staff often receives inquiries from the ministry about salary ranges for professional ethicists. Needless to say, these vary considerably, depending on the size of the system or facility, the region of the country, and the title, responsibilities, education and experience of the candidate. The survey showed the following overall salary ranges:

- 2.3 percent of professional ethicists earn more than $300,000

- 9.3 percent earn between $200,001 and $300,000

- 20.9 percent earn between $150,001 and $200,000

- 30.3 percent earn between $100,001 and $150,000

- 37.2 percent earn $100,000 or less

As might be expected, ethicists employed by a national system earn more (63 percent earn between $125,001 and $200,000) than those employed by a regional system (approximately 61.1 percent between $50,000 and $100,000, 16.6 percent between $100,001 and $125,000, and 16.6 percent between $125,001 and more than $200,000), or by an acute care facility (75 percent indicated salaries between $35,001 and $75,000, while 25 percent indicated a salary between $125,001 and $150,000).6

Survey results showed the following salary ranges for responding mission leaders: 12.9 percent earn between $200,001 and $300,000; 8.4 percent between $150,001 and $200,000; 41.3 percent between $100,001 and $150,000; 37.4 percent less than $100,000. Mission leaders in long-term care earned the least (64 percent earning between "less than $50,000" up to $75,000.)

When broken down by location, survey results showed that 48 percent of mission leaders at the regional system/acute care facility levels earn between $100,001 and $150,000, while 30 percent at the national system level earn between $125,001 and $150,000. Another 30 percent at the national system level earn between $200,001 and $300,000.

4. Concerns about Age

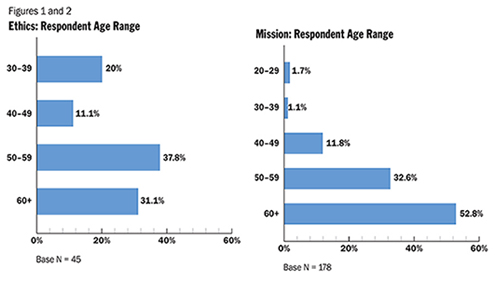

A survey result of significant concern is the age of professional ethicists in the ministry. The largest percentage, 37.8, is between the ages of 50 and 59, and 31.1 percent are 60 and above. This means that 68.9 percent of ethicists are 50 years old or older. Another 11.1 percent are in the 40-49 age range, and 20 percent are between 30-39. (We are confident there are a few ethicists in their late 20s, but they either did not respond to the survey or did not respond to this question.)

These numbers not only suggest an aging cohort of professional ethicists, but also, of even greater concern, disproportionately fewer ethicists coming into Catholic health care than those approaching retirement age. Absent some fairly aggressive measures, we are facing a shortage.7 Leaving these positions vacant or filling them with individuals who might not have the desired qualifications, competencies and experience could eventually have a negative impact on ethics in Catholic health care at a time when the issues are becoming increasingly complex.

As with the professional ethicists, the age range of mission leaders with responsibility for the ethics function is of considerable concern (see Figures 1 & 2). Among these individuals, 52.8 percent of respondents are over 60 years of age and 32.6 percent are between 50 and 59. Put more dramatically, 85.4 percent are over the age of 50. Only 1.7 percent is between 20 and 29, and only 1.1 percent are between of 30-39. In the 40- to 49-year-old category, we find only 11.8 percent. In other words, only 14.6 percent of mission leaders doing ethics in their organizations are younger than 49.

When combined with the ages of professional ethicists, and barring some significant reversal of the trend, it is evident that Catholic health care is rapidly facing serious shortages of those doing ethics in the ministry.

5. Titles and Reporting Relationships

Because titles may indicate the degree to which a particular role is valued by an organization, our survey asked about position titles of trained ethicists and the titles of those to whom they report. Position titles range from ethicist (five respondents), to director (16 respondents), to vice president (nine respondents), to senior vice president (one respondent).

As might be expected, a majority of ethicists (62.5 percent) report to a mission leader, while 30 percent report to "other," and 7.5 percent report to medical affairs. Of those reporting to a mission leader, 34.9 percent report to a senior vice president, 25.6 percent to a vice president and 11.6 percent to a director.

With regard to reporting relationships, a slight majority (51.7 percent) of responding mission leaders report to "other" (in most cases, the chief administrator of the institution), while 36.2 percent report to another mission leader and 8.7 percent to pastoral care.

The difference in reporting relationships is telling. The majority of professional ethicists report to a mission leader, whereas a slight majority of mission leaders who carry out the ethics function report directly to the chief administrator. This could be purely by happenstance or it could say something about attitudes toward the importance of ethics within the organization and the status of the professional ethicist. The difference merits further examination and discussion.

What Do They Do and Think About?

1. Roles and Responsibilities

In an attempt to obtain a better picture of what professional ethicists do, the survey asked them to indicate their primary roles and responsibilities from a provided list. Not surprisingly, the roles and responsibilities that rose to the top were education (89.8 percent), working with ethics committees (79.6 percent), clinical consultations (73.5 percent), development of educational resources (73.5 percent), policy development (71.4 percent), advising leadership on organizational issues (69.4 percent), and leadership development (59.2 percent). Less frequently mentioned were research (51 percent), church relations (49 percent) and writing for publication (46.9 percent).

With few exceptions, responses from ethicists working out of a national system office were similar to those of ethicists working for a regional system or acute care facility. In all probability, however, while little difference exists in stated roles and responsibilities, differences occur among the three groups in the manner and degree in which those roles and responsibilities are carried out on a daily basis.

Mission leaders' primary roles and responsibilities in carrying out the ethics function differ just slightly from those of the professional ethicists. Their two top roles/responsibilities are working with ethics committees (76 percent) and education (65.4 percent), just the reverse of ethicists. Other roles and responsibilities are comparable with the exception of research and writing for publication. Mission leaders rank these as 6.7 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively, whereas professional ethicists rank them as 51 percent and 46.9 percent, respectively. These differences might be explained in part by the two groups' different locations and training.

2. Daily Activities

By far the most frequently mentioned activity for ethicists was education (69.4 percent). Distant seconds were clinical consultations (26.5 percent), advising leadership on organizational issues (20.4 percent), working with ethics committees (20.4 percent), and development of educational resources (16.3 percent). Even lower on the scale were research, writing for publication, and policy development, each at 6.1 percent. Leadership development was at 2 percent, and church relations was almost zero. These results would seem to suggest that specified roles and responsibilities, as set forth in position descriptions, correlate only roughly with how professional ethicists actually spend their time. More importantly, they suggest something about desired competencies. It may well be that the activities that occupy ethicists from day to day should drive desired competencies rather than a general position description.

What occupies the time, energy, and attention of mission leaders as they carry out their ethics function? It should be noted that the amounts of time mission leaders spend doing ethics varies widely. The vast majority (82.2 percent) spend a quarter or less of their time in this role, and 14 percent spend 26 to 50 percent. Only 3.8 percent spend 51 to 75 percent or more of their time in an ethics role.

These results raise serious concerns. The vast majority of mission leaders who also carry out the ethics function spend a quarter or less of their time doing ethics. This is not the fault of mission leaders; most wear multiple hats and are stretched thin. This is a leadership and organizational issue. What does it say about how ethics is valued, how it is understood, and how it is done (i.e., quality), if it is receiving a quarter or less time of someone's attention, even if this person's efforts are supplemented by an ethics committee?

Professional ethicists and mission leaders are further differentiated by the activities that take priority as they carry out the ethics function. Mission leaders rank working with ethics committees (43.6 percent) higher than education (26.3 percent) — functions that are reversed by ethicists in terms of time spent. Among responding mission leaders, 45.5 percent indicated they chair the ethics committee. Another 26.6 percent serve as a member of the committee, and 18.8 percent serve either as the responsible staff person or as a resource to the committee. Mission leaders rank leadership development higher than do ethicists, whereas ethicists rank development of educational resources higher. Writing for publication and research occupy the least amount of mission leaders' time (.6 percent and .3 percent, respectively). Both rank higher for ethicists, but leadership development is near the bottom.

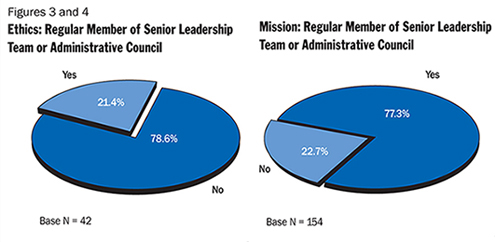

Respondents in both groups were asked whether they are a regular member of the senior leadership team or the administrative council (see Figures 3 and 4 below). The vast majority of mission leaders, 77.3 percent, reported that they are, whereas 78.6 percent of ethicists reported they are not. This should not necessarily be construed to mean that ethicists have little influence on senior leadership. What it does mean is that senior leadership may need to examine the degree to which ethics is valued in the organization, as well as how ethics is brought to bear on all dimensions of organizational life, including those areas of the organization represented by senior leadership. What is important is that ethics is brought to bear, and not so much how it is brought to bear.

Some clarity about how the ethicist exerts influence is critical to the success of the role. Those ethicists who do not sit at the senior table might do well to examine how they exert influence on the organization as a whole as well as on senior leadership. Is it by participating in discussions on an ad hoc basis, through face-to-face conversations with senior leaders, or through the mission leader or another person to whom the ethicist reports?

3. Issues Occupying Attention

What occupies ethicists' and mission leaders' time are not only particular activities, but also particular issues that those activities address. Respondents were asked about the ethical issues that had been most pressing in the 12 months prior to the survey.8 The most frequently mentioned issues by both groups were end-of-life care and futile treatment.

These results seem to point to a challenge that merits further exploration. Among the next top five issues, mission leaders and ethicists have two others in common, though rank them differently — education of leadership and staff (3.3 percent for mission leaders and 15.7 percent for ethicists) and contraception and reproductive issues (6.9 percent for mission leaders and 8.7 percent for ethicists). Mission leaders include physician/family conflicts (3.9 percent) and insurance and access to care issues (3.6 percent) in their top five issues, while ethicists do not.9

4. Professional Development

Responses to questions relating to professional development suggest something about the professional self-identification and interests of ethicists in the ministry. A majority, 56 percent, said they attend one to three conferences per year,10 while 34.1 percent attend four to six. These include the annual meeting of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (51 percent) and the CHA Colloquium (75 percent). Smaller numbers attend annual meetings of the Catholic Theological Society of America and the Society of Christian Ethics: 14.3 percent and 10.2 percent, respectively.

A strong majority of mission leaders (75.8 percent) attend one to three ethics-related conferences per year. Reading articles and books and attending workshops are among activities that help mission leaders keep up.

Both groups were also asked about the most critical topics for the continuing education of ethicists in Catholic health care. Fifteen percent of ethicist respondents noted theological foundations, 14 percent mentioned ethical issues related to research and advances in biology and science, 12.1 percent indicated the history and evolution of Catholic health care and organizational and business ethics, and 9.3 percent listed end-of-life issues and futile treatment. Mission leaders differed somewhat, listing the following in their top five: end-of-life and futile treatment issues (17.2 percent), cutting edge science/genetics/genomics (13.4 percent), the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (7.5 percent), health policy and economics (6.7 percent), and organizational and business ethics (4.9 percent).

What is most satisfying to ethicists about their work is making a difference and helping others (50 percent) and education of staff and community (22.5 percent). The most oft-cited challenge was addressing structural and educational issues (38.9 percent), followed by limited time, resources, and unrealistic expectations (22.2 percent), demonstrating the value of their role (19.4 percent), and lack of organizational focus on mission to guide decisions (11.1 percent). Conversations about these challenges between ethicists and the person to whom they report might prove valuable.

Mission leaders listed making a difference and helping others (29.3 percent) as the most satisfying aspect of their work, followed by living and sharing Christian values in an ecumenical setting (22.0 percent) and respect for colleagues and the organization (17.1 percent). The greatest challenges for mission leaders in carrying out the ethics function are addressing structural and educational issues (32.5 percent), limited time, resources and unrealistic expectations (15.4 percent), end-of-life issues (8.9 percent) and demonstrating the value of the ethics role (8.1 percent).

Perceptions of Ethics Within Organizations

1. Attention to Ethics by Senior Leadership

Both ethicists and mission leaders were asked about their perceptions of various dimensions of ethics within their organizations. One question inquired about the amount of consideration given by senior leadership to ethics in various areas; namely, mission, patient care, advocacy, leadership development, policy setting, strategic planning, human resources, budgets and medical affairs. Ethicists ranked mission, patient care and advocacy the highest; human resources, budgeting and medical affairs the lowest. Mission leaders gave a similar assessment, ranking mission and patient care the highest, and medical affairs and budgeting the lowest. The two groups differed, however, with regard to advocacy and human resources. Mission ranked advocacy among the bottom three categories, while ranking human resources among the top four. They ranked policy setting as third.

2. How the Ethics Function Is Valued

Both groups were also asked about the degree to which the ethics function is valued by sponsors, mission leaders, the CEO, nurses and clinical staff, board members, senior leadership, patients and physicians.

It is encouraging that both groups ranked the CEO among the top three, but of some concern, is that they both listed physicians in the bottom three. Whether the reason(s) for the poor showing of physicians are benign or problematic, they may well be worth some discussion at the local level.

3. Ethics in Strategic Planning

When asked about their perceptions of the degree to which ethical awareness is integrated into strategic planning, 30.8 percent of ethicists said considerably/very, and 51.3 percent replied little/not at all. Mission leaders, on the other hand, perceived greater attention to ethics in strategic planning, with 43 percent replying considerably/very, and just 28.1 percent saying little to not at all. The difference could be explained by the greater proximity of many mission leaders to the strategic planning process.

4. Budgeting for Ethics

The existence and extent of a budget may indicate how a particular service or program is valued. Both groups were asked about the presence of a budget for ethics and its adequacy. The majority of ethicists (77.5 percent) responded that there is a budget, with just 42.8 percent describing it as considerably or very adequate. Mission leaders' responses were nearly reversed. The majority (77.1 percent) have no separate budget for ethics; 34.8 percent describe the ethics budget as barely or not at all adequate. These results, too, merit further exploration and discussion. It could be, at least in some cases, that the ethics budget is folded into the larger budget for mission.

5. Contributions of Ethics to the Organization

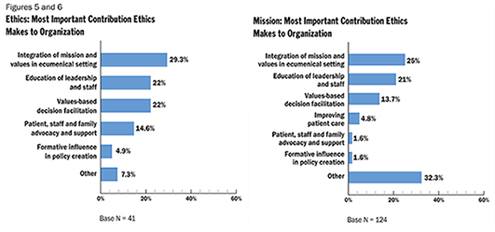

Asked to rank in order of importance the contributions ethics makes to their organizations, ethicists chose integration of mission and values in an ecumenical setting (29.3 percent), education of leadership and staff (22 percent), and values-based decision facilitation (22 percent) as their top three. Patient, staff and family advocacy and support ranked fourth, at 14.6 percent. Mission leaders had the same top three at 25, 21, and 13.7 percent respectively, but they ranked improving patient care fourth at 4.8 percent. It seems significant that both groups agree on the top three contributions (see Figures 5 and 6).

Looking to the Future

Survey questions related to the future of the profession dealt primarily with preparation of ethicists and the contributions of ethics to Catholic health care organizations and to the ministry.

1. Desired Core Competencies

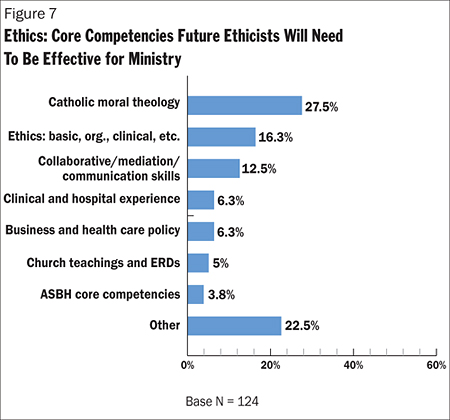

Asked what core competencies future ethicists would need in order to be effective in the ministry, ethicists cited Catholic moral theology (27.5 percent), basic, clinical and organizational ethics (16.3 percent), mediation and communication skills (12.5 percent), clinical experience (6.3 percent), business and health care policy (6.3 percent), church teaching and the ERDs (5 percent), and the core competencies developed by the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (3.8 percent).

Mission leaders mentioned church teaching and the ERDs most often at 21.3 percent, followed by mediation and communication skills (15.4 percent), basic, clinical and organizational ethics (14.7 percent), medical and technological advances (8.1 percent), Catholic moral theology (6.6 percent), values-based decision-making (4.4 percent), clinical experience (2.9 percent), cultural diversity (2.2 percent), and business and health policy (1.5 percent).

When broken down by location, mission leaders with national systems indicated Catholic moral theology and church teachings and the ERDs at the top, while those at the regional system and acute care levels most often mentioned church teachings and the ERDs and collaborative/mediation/communication skills.

It would be interesting to know why ethicists ranked Catholic moral theology first and church teaching and the ERDs considerably lower, while mission leaders ranked them just the opposite. The fact that both groups listed basic, clinical and organization ethics and mediation and communication skills among the top three desired core competencies is notable.

2. Desired Employment Experience

A follow-up question asked about relevant employment experience desired for future ethicists in the ministry. The responses to this question by the two groups were interesting. For both ethicists and mission leaders, the most desired employment experience is clinical/hospital/health care experience (50.9 percent for ethicists and 54.3 percent for mission leaders). Moving down the list, however, the two groups diverged. Ethicists preferred teaching experience (12.7 percent), some experience with business and complex organizations (10.9 percent), and ethics training/mentorships/fellowships (9.1 percent). The mission leaders' responses, no doubt reflecting their somewhat different roles and responsibilities, were mission and pastoral care (12.1 percent), ethics training/mentorships/fellowships (7.8 percent), ethics committee experience (6 percent), teaching (5.2 percent) and some experience with business and complex organizations (2.6 percent). Even though the rankings of each group varied, the fact that each identified similar desired employment experience is important in developing position descriptions and in assessing candidates for positions.

3. Essential Educational Preparation

Asked about essential educational preparation for someone doing ethics in the future, a slight majority of ethicists (51.3 percent), most at the national system level, cited a Ph.D., while 35.9 percent, mostly at regional systems and acute care facilities, cited a master's degree. Another 10.3 percent indicated a professional degree and 2.6 percent a certificate in ethics. Interesting, but unsurprisingly, 49.6 percent of mission leaders believe that a master's is essential educational background and 31.9 percent believe that a certificate in ethics is essential. Only 4.4 percent of mission leaders, the majority of whom worked at the national system level, indicated a need for a Ph.D.

Determining adequate and desired educational preparation for someone doing ethics in Catholic health care is a high priority goal in planning for the future, one that merits much more discussion. Is a master's degree sufficient for a professional ethicist? Does it matter whether that individual is employed by a national system, a regional system, or an acute care facility? Is it sufficient for a mission leader who is also responsible for the ethics function to have a certificate in ethics?

4. Recruiting Future Ethicists

Ethicists were invited to offer suggestions for attracting/recruiting future ethicists for the Catholic health ministry, a relatively urgent issue that calls for ministry-wide attention. Their top suggestions were the following: build a pipeline to universities (19.2 percent); develop a greater understanding of the role (11.5 percent); provide mentorships and fellowships (9.6 percent); offer attractive salaries and benefits (7.7 percent); and emphasize the ability to make a difference (7.7 percent).

5. Ethics' Contributions to Organizations and the Ministry

Shifting gears, the survey asked how ethics could contribute most to the responder's organization in the next three to five years. The top five suggestions by ethicists were: education of leadership, staff and the public (30.6 percent); better acceptance and integration of ethics as a resource by the executive level (14.5 percent); influencing policy development (12.9 percent); values-based decision facilitation (11.3 percent); and providing better tools for dealing with problems (11.3 percent). Mission leaders agreed with the top major contribution (22.3 percent), but differed in their next three: linking mission, core values, and vision with everyday behavior (17.3 percent); patient, staff, and family advocacy (11.2 percent); and providing an ethical framework and ethical oversight (6.7 percent). The fifth top contribution was values-based decision-making.

A follow-up question asked how ethics could contribute most to the ministry in the same time period. The top four responses for both ethicists and mission leaders were: patient, family, and staff advocacy and support; linking mission, core values, and vision with everyday behavior; education of leadership, staff, and the public; and influence in policy development. The two groups, however, ranked these contributions in a slightly different order.

Concluding Observations

This article began with a question about the future of ethics in Catholic health care. The results of CHA Ethics Survey, 2008, seem to suggest, at minimum, that far more attention needs to be paid to the ethics function in our organizations. The responses also raise some red flags about dimensions of the role as it exists today and into the future. Readers will have their own interpretations and observations regarding the results, but the following questions and observations are offered here.

1. We have an aging cohort of professional ethicists and mission leaders with responsibility for the ethics function. This challenge is compounded by the fact that there are insufficient numbers of younger individuals to replace them. Given this, what will happen to the ethics function in the future? And, if it continues, who will carry it on? Will they be adequately prepared?

2. What is the appropriate educational background for those with the ethics role in Catholic health care organizations — national and regional system offices, acute care and long-term care facilities? What are the qualifications and competencies that can be expected and that would enable those with the role to be as effective as possible? The survey suggests great variability. This is an area where there has never been sustained discussion on a national level. Related to this is the degree to which a theological background is desired in those individuals who carry out the ethics function. Again, survey responses reflect some variability. Why or why not is theological preparation a necessary qualification, especially for professional ethicists?

3. The survey results raise the question about how much the ethics role is valued by leadership within our organizations and whether ethicists are utilized in the most effective manner. Are ethics and the ethics role viewed as integral to the life of the organization or are they seen as nice to have around when crises develop or other difficult problems arise? How is the ethics role positioned and how is it used? What are expectations of those who hold it?

4. What does it say about the place of ethics in our organizations when the majority of people responsible for it (mission leaders who also have the ethics function) spend less than a quarter of their time doing ethics and seem to have minimal preparation for this part of their responsibilities? This is not meant as a criticism of mission leaders and their hard and good work. It is a question for leadership. Would we do the same for other roles — human resources, for example, or quality assurance or strategic planning?

5. Those who do most of the ethics in our organizations seem to spend a good deal of their time addressing clinical issues and working with their ethics committees, and devoting little attention to organizational ethics. This is good as far as it goes, but health care ethics needs to encompass all dimensions of organizational life. The current way of doing things seems to perpetuate an outdated understanding and approach.

6. Important similarities in the responses to a number of important issues between ethicists and mission leaders are present, but differences also exist. What is the significance of these differences? Do they complement one another? Or do they result in working in cross purposes? What is their overall impact on ethics in the ministry? This needs further analysis and discussion.

7. Research and writing for publication rank low for both professional ethicists and mission leaders. It is unclear whether this is because it simply takes up less time than other activities or whether neither is being done much. The latter would be very unfortunate. No one is better positioned to contribute to the field of Catholic health care ethics than those who do it. The field will suffer incredibly and the ministry will be short-changed if we fall short in this regard.

These observations, indeed the survey results themselves, are intended to stimulate conversation in our organizations about how we understand, organize, and do ethics. They suggest we are at a critical juncture. We hope that insights, observations and conversations from readers will lead to some rethinking and to some concrete steps to enhance the ethics role in Catholic health care. Doing nothing does not portend well for the future of ethics and the ethics role in the ministry.

NOTES

- John Glaser, "Hospital Ethics Committees: One of Many Centers of Responsibility," Theoretical Medicine 10 (1989): 278.

- For further discussion of this, see Ron Hamel, Organizational Ethics: Why Bother?" Health Progress 87, no. 6 (2006); 4-5; "New Directions for Health Care Ethics?," Health Progress 88, no. 1 (2007); 4-5; and "Ethics — Fostering an Ethical Culture: Rules Are Not Enough," Health Progress 90, no. 1 (2009); 10-12.

- Some systems and facilities do not have a full-time ethicist, but employ the part-time services of an ethicist who is generally based in a bioethics center or a university or seminary department. By "professional ethicist," we mean someone who holds a graduate degree in ethics and whose profession is ethics.

- These mission leaders are to be distinguished from those who have oversight responsibility for ethics (e.g., overseeing the ethicist, the ethics consultant, and/or the ethics committee), but do not themselves "do ethics."

- The two surveys and the complete results for each can be found at www.chausa.org/ethicssurveyresults. Many of the insights and comments from both groups are woven into this article.

- American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, "Salary Survey," www.asbh.org/salary.html.

- This is true not only in Catholic health care, but also in academic institutions (with the exception of those that have bioethics centers). There are fewer academics recognized as specializing in bioethics or health care ethics. One consequence of this is that few graduate students in Catholic universities are specializing in bioethics.

- This was an open-ended question. For this reason, the responses were extremely varied. In addition, respondents often used different language to express the same or a very similar issue. In compiling and reporting the results, we grouped similar responses into categories. There were many single responses. These were grouped under "other." The listing of all responses under "other" can be found on the CHA website, www.chausa.org/ethicssurveyresults, with the survey results. What is true of this question in the survey is also true of several others.

- Both groups were also asked what they believed the key issues would be in the next three to five years. Results can be seen on the CHA website, www.chausa.org/ethicssurveyresults.

- Both groups were also asked what publications and what websites they rely on for information on health care ethics. These results can also be viewed on the CHA website, www.chausa.org/ethicssurveyresults.

Copyright © 2009 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.