BY: KAREN SUE SMITH

The text below is an official summary of a CHA white paper, "Caritas in Communion: Theological Foundations of Catholic Health Care," prepared as part of a three-year study of CHA's membership criteria.The full-length white paper is available at the CHA website, www.chausa.org.

Catholic health care finds itself within a rapidly changing landscape. In response, some Catholic hospitals and collaborative health systems are making structural changes. Some systems have decided to forego formal recognition by the local bishop, for example, while a few hospitals and systems have begun to explore for-profit corporate structures. These and other new models-in-the-making may have deep, far-reaching implications for their ministries, implications still unknown. Meanwhile, the self-identity of many of these institutions is changing. Mixed models of identity have emerged, models no longer solely Catholic but with ecumenical, interfaith, or secular dimensions. Mixed models of identity intensify such basic questions as: What makes Catholic health care Catholic? Can an organization maintain its Catholic identity if it is owned and/or managed by a non-Catholic organization? If so, how? How might for-profit status affect Catholic identity?

For the Catholic Health Association, these new developments also raise a practical issue. Currently, the association's criteria for membership require both "not-for-profit" status and recognition as Catholic by the local bishop. Given this disconnect, the CHA Board has outlined a three-year discernment process to help members reflect on the theological foundations of Catholic health care (year one), consider in light of those foundations the experience of members that have adopted new models (year two), and revisit the CHA membership criteria (year three).

"Caritas in Communion," the study upon which this summary is based, is a fruit of year one. Written with wide consultation, it accounts for the theological commitments that ground Catholic health care ministry. Specifically, the study examines the theological foundations of three pivotal issues: Catholic identity in Catholic health care, the principle of moral cooperation used to assess partnerships between Catholic and other institutions and Catholic economic thought as it pertains to for-profit status in health care.

In framing and analyzing how the new models relate to traditional Catholic health care organizations, a series of questions may prove helpful. What is the religious identity of the parent organization? Of individual hospitals? What is the for-profit/not-for-profit status of each? How are the relationships between Catholic and non-Catholic components of the system structured? What is the relationship between the system, hospitals, and the local bishops? What is the role of the sponsors?

CATHOLIC IDENTITY

Catholic health care organizations are envisioning new ways to maintain their Catholic identity within new structures. They are taking steps to remain in relationship with the local bishop and the sponsors. They continue to follow the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, to offer pastoral care and the sacraments, and to provide charity care. Are all of these vital to Catholic identity? Are they sufficient?

Catholic identity is a complex term. Its meaning has been debated since the 1970s. "Identity" itself has many dimensions. It concerns intrinsic characteristics of a person or institution that are consistent over time, are perceivable by others, distinguish a person or institution and connect them to others. Yet identity also develops over time in response to experience. All persons and institutions embody multiple identities simultaneously. Discerning the core characteristics of one's identity is an ongoing process attuned to place and time. Catholic identity is embedded in Catholic tradition, which includes spirituality and prayer, the church's sacramental and liturgical life and official church teaching. While Catholic identity is neither fixed nor complete, it does have roots. And it should be perceptible to others. We ask, Who do we say we are? in order to discern who we are called to be, and what we ought to do in new situations.

Consensus is emerging around seven characteristics of Catholic identity in health care. Catholic health care is rooted in and continues to make present in the world: (1) the healing ministry of Jesus, (2) the stories of the founding congregations and (3) the social teaching of the church. Catholic health care is also (4) a ministry of the church, (5) a sacrament or sign of Christ's presence, (6) a way of being in communion with the church and (7) a means of witnessing to the faith.

Beneath the key characteristics we find several theological concepts that ground Catholic identity. Catholic health care draws its identity, for example, from a balanced Christology based on Jesus' dual nature as both human and divine. The results are practical. In continuing the healing ministry of Jesus, Catholic health care tends to body and spirit, to the welfare of patients and their families, as well as to staff/employees. Similarly, the stories of the founding congregations not only inspire us, but invite us to share their charism and close links to Jesus, bringing that grace and power into the present. The church's social teaching —with its emphasis on human dignity, the common good, stewardship, solidarity, subsidiarity, care for the whole person, concern for the poor and vulnerable — also is made present, affirmed in the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, in employee compensation and benefits, in charity care and other ways.

Catholic health care recognizes itself as a ministry, though historically the word "ministry" has been limited to the work of the clergy. The Second Vatican Council's "Dogmatic Constitution on the Church" (Lumen Gentium), however, shifted the sacramental basis of Christian work in the world from ordination to baptism. Since then, theology has begun to describe the work of the laity, grounded in baptism, as ministry. This theology is still evolving. So far, neither lay ecclesial ministry (modeled on parish life) nor the works of religious institutes is an exact fit for Catholic health care.

Ecclesiology (the theology of the church) also is evolving in its understanding of church as communion. The "communion ecclesiology" of Vatican II presents the church as founded in baptism and created anew each time the Eucharist is celebrated. The people of God who make up the church share the "priesthood of the faithful." Historically, for Catholic health care to be in communion meant to have validation from the local bishop. Today that seems insufficient as health care systems now extend beyond diocesan borders; the link with the church needs clarification. In the 1980s, Catholic health care developed the role of sponsor and appropriated the canonical "public juridic person" in an effort to maintain an official connection between religious institutes, their lay-led ministries and the church. Sponsorship continues to move Catholic health care toward a more complete understanding of communion ecclesiology, a fuller vision of the shared work of laity, vowed religious and bishops.

Jesus commissioned the church to be the visible sign (or sacrament) of God's salvation. Thus sacramentality is central to Catholic health care. Catholic institutions not only continue to provide the sacraments to patients and staff, they perform their daily work as a visible sign of Christ in the world. Those who work in Catholic health care are called to embody Christ as healer. This sacramentality includes ordinary moments, like serving hospital food, wiping the drool from the chin of an Alzheimer's patient, covering a naked patient and other daily encounters — occasions of grace.

Witnessing to the faith is reflected in the way Catholic institutions treat persons of all faiths or no faith. To witness does not mean to proselytize, even though some patients and staff, influenced by the lives of nurses and other practitioners, have converted or become reconciled to God. Witness is the way Catholic health care, by continuing God's healing work, invites people to God.

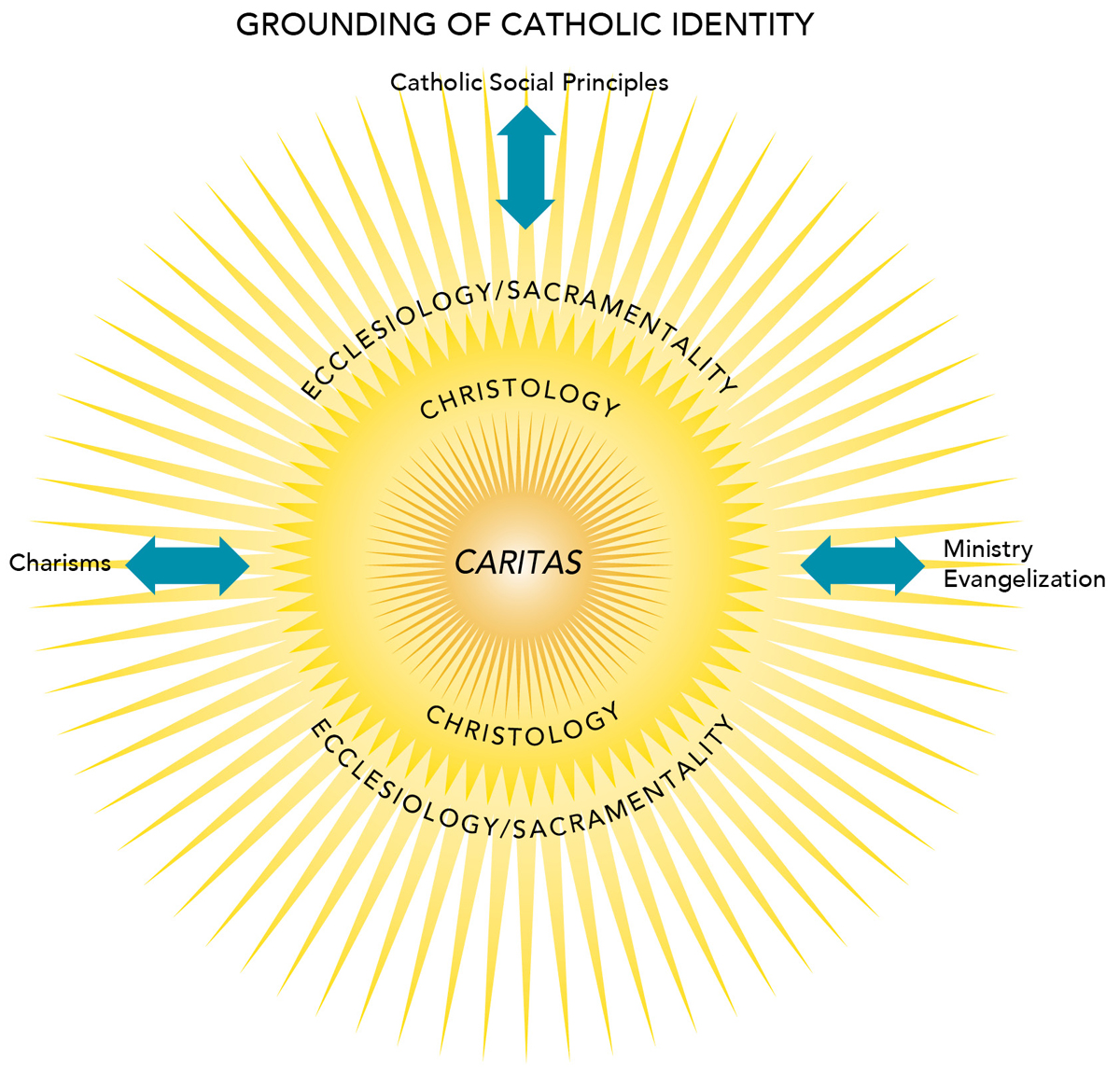

These seven characteristics of Catholic identity are interrelated in layers around caritas ("love" or "charity" in some translations). Caritas is the theological reality upon which the cosmos is created and sustained, thus the bedrock on which Catholic health care stands. Pope Benedict XVI's encyclicals "God is Love" (Deus Caritas Est) and "Charity in Truth" (Caritas in Veritate) describe caritas, a concept that far exceeds the notion of "charity care." Caritas is the very essence of God. It is the way God interacts with the world. Caritas is essential to all that derives from God. It follows that caritas is the essence of the person Jesus Christ; the essence of the church; the essence of the sacraments by which we encounter God; the essence of ministry; the essence of witness; the essence of Catholic social principles; and the essence of the stories of the founders of Catholic health care.

Catholic health care is a concrete practice of love. It takes shape as a communion of people engaged in ministry and witness, steeped in Catholic social thought and the Spirit-led charisms of our founders, which continue to inspire our ministry. Catholic health care is sacramental, grounded in an ecclesiology rooted in Christ, the summit and fullness of God's caritas in the world.

PRINCIPLE OF MORAL COOPERATION

Catholic health care tries to demonstrate caritas, showing what health care looks like when shaped by a community witnessing to God's love. Yet Catholic identity has been difficult to maintain within the traditional models. How might emerging models further complicate the challenges?

To date, the ethical principle of moral cooperation has been a primary lens used to assess the implications of partnerships between Catholic and non-Catholic organizations. The principle enables us to determine what involvements with others are morally acceptable. It suggests what to do when one discovers that the good one does involves one in some wrongdoing of another. Yet as used in Catholic health care today the principle has limitations. For one thing, the principle was developed in the 16th century to help priests hear confessions, assess sins and assign penances, leading a penitent to reconciliation. Since the 1990s, moral theologians have debated whether the principle is applicable to institutions like health care. Also, the principle does not reflect the robust ecclesiology emerging from Vatican II in which the church, seeing itself as a part of the modern world, is obliged to engage with it. A more fully developed "theology of cooperation" on which to ground the principle may help Catholic health systems determine how to advance the Kingdom through non-Catholic structures.

The writings of popes Paul VI, John Paul II and Benedict XVI have begun to articulate such a theology. The church has recognized that Christians have a positive obligation to cooperate with others, including the State, non-Catholics and those of other faiths. In "Charity in Truth" Benedict states the basis for collaboration, describing the human race as "a single family working together in true communion." Joint efforts with others must be mutual and transparent, Benedict writes. And partners in collaboration must be open to faith that is "purified by reason" and reason "purified by faith." The purpose of collaboration is to further justice, peace and human development.

Benedict identifies the primary theological grounding for the mandate to collaborate as the doctrine of charity (caritas). He finds additional grounds for collaboration in theological anthropology, ministry and evangelization, the church's social teaching and the goodness of creation. Benedict's theology reveals a positive understanding of the relationship between church and world. Moreover, laypersons are to be the primary agents of this collaboration. In 2012, Benedict forcefully said that laypersons should "not be regarded as 'collaborators' of the clergy but rather as people who are really 'co-responsible' for the church's being and acting."

The principle of cooperation and assessments about Catholic partnerships, then, must be interpreted and applied within a rich theology of cooperation. That theology has roots in the unity of the human family and in the doctrine of caritas. It reflects a positive vision of relations between church and world and an increasing appreciation of the co-responsibility of the laity for the church.

In light of current papal theology, then, Catholic health care finds itself not only permitted to enter into partnerships with other faith-based and secular organizations; it finds a positive obligation to engage in "fraternal collaboration between believers and non-believers" ("Charity and Truth"). Consider that throughout the world, access to affordable care is an issue of justice and peace. Often the health needs of the public are more effectively served by collaborative efforts. In Catholic health care these efforts are typically lay-led. Collaboration between Catholics and non-Catholics bears fruit for the Gospel and human development in society. Catholic systems in partnership not only deliver health care across populations, especially to the poor and marginalized, but have been remarkably successful in influencing other institutions to adopt many Catholic values. Their success in achieving practical moral consensus is unparalleled in the United States.

This theological analysis calls for a new approach to the principle of cooperation, one that moves discussions away from a narrow focus (on reproductive issues, for example) toward the overall mission of Catholic health care. Conversation would build on the goods we hold in common. It would follow the church's approach to the collaboration of institutions in the social sphere, rather than of individuals in the personal sphere. And it would align the principle of cooperation with Catholic social thought regarding the promotion of the common good and the proper subsidiarity of non-Catholic partners.

If non-Catholic (secular) not-for-profit parent organizations are structured to allow all participants their proper subsidiarity, they may prove amenable to the maintenance of Catholic identity within hospitals and subsystems. They may even allow for a greater range of Catholic partnerships with other faith-based or secular providers of health care, increasing the scope of the work of charity in the world.

The main question regarding new partnerships is: Does the structure of a proposed organization — especially where one party is managed by the other — diminish/preserve/enhance the mutuality necessary for dialogue and true collaboration?

THE FOR-PROFIT QUESTION

Since there is no authoritative doctrinal teaching on the question of whether Catholic ministries ought to adopt for-profit or not-for-profit corporate status, this paper outlines the theological parameters for discernment. The goal is to shed theological light on the question: Is a shift to for-profit status for an organization in Catholic health care consistent with Catholic identity? To do so, we look at magisterial teaching on economics, applicable social questions and the theology behind them.

First, two definitions. A for-profit corporation (whether publicly traded or privately held) is one that intends to maximize the shareholder value, which can include returning a portion of surplus revenues to owners or investors. A not-for-profit corporation cannot distribute surplus revenues as profits or dividends to owners or investors, but rather must use surplus revenues to achieve other specified goals; these goals include preserving or expanding the corporation itself or funding community goods.

The main concern about shifting to for-profit status in Catholic health care is "shareholder primacy." Shareholder primacy holds that corporations are obligated to make profit for owners the primary end to which all other ends are secondary. A strong cultural assumption, taught in business schools and upheld in case law, is that for-profit corporations are obliged to maximize profits for shareholders. Still, as some have argued, pursuit of humanitarian, charitable, social or other stakeholder objectives is legally within the discretion of for-profit corporate leadership.

Catholic social doctrine speaks of the economy in particular terms. It speaks of integral human development, the dignity and priority of labor, structures of sin and solidarity, private property and the universal destination of goods and the principle of gratuitousness. All five principles bear on our question.

- Integral human development places corporate profits in subordination to other goods, such as the full flourishing of the common good. As John Paul II writes in "On Human Work," integral human development through work "does not impede but rather promotes the greater productivity and efficiency of work itself."

- Regarding human labor, John Paul II affirms the priority of labor over capital, of persons over profit. The reason is that work is more than wages. Work is the primary activity by which persons move toward their fulfillment and advance toward human flourishing.

- As for structures of sin, John Paul II urges the citizens of rich countries to examine their relationship to world poverty. He points to the "all-consuming desire for profit" as an example of structural sin that misdirects economies in ways that cause or perpetuate poverty. The antidote is solidarity with others and a commitment to the common good.

- Catholic teaching, from the papacy of Leo XIII, has upheld the right to private property. But John Paul II also notes limitations on the right, which concern the universal destination of goods. Since the goods of creation are given by God for all, the right to private property is always qualified by the basic needs of others for material survival and the good of the community.

- In "Charity in Truth," Benedict XVI adds the principle of gratuitousness to Catholic economic thought. Since God's presence and all the goods of creation are freely given to the world, then "economic, social and political development ... needs to make room for the principle of gratuitousness as an expression of fraternity." Benedict challenges the marketplace, especially Catholic institutions, to create space "for economic activity to be carried out by subjects who freely choose to act according to principles other than those of pure profit, without sacrificing the production of economic value in the process. The many economic entities that draw their origin from religious and lay initiatives demonstrate that this is concretely possible." The powerful economic reality of Catholic health care was (and still is) made possible by the logic of gift.

Whereas in unbridled capitalism the human person may be reduced to an instrument of production, in Catholic thought, capitalism is always bridled by the dignity of the human person and the common good of society. John Paul II urges Christians to pursue profit "with a deeper concern for the spread of solidarity and the elimination of the scourge of poverty." Profit cannot be the sole or even primary factor directing corporate life. Instead, John Paul II sees labor and capital as interdependent — a business can be jointly owned, its profits shared with workers, its corporate decisions made with worker input. Benedict proposes the creation of "hybrid forms of commercial enterprises." If the economy is to be "civilized," to aim at a higher goal than mere profit, writes Benedict, there must be room for "commercial entities based on mutualist principles and pursuing social ends to take root and express themselves."

Consider four real-world examples of alternative corporations that put people above profits: the Mondragon Corporation, a major employer in Spain; the Economy of Communion, a worldwide organization begun in Brazil by Chiara Lubich, founder of Focolare; the Grameen Bank, a microlender founded in Bangladesh by Muhammed Yunus; and the "Benefit" corporations or "B-Corps," which seek to influence society and the environment positively in addition to making a profit. These hybrids embody commitments like those of U.S. not-for-profit corporations, particularly community benefit.

Catholic social thought calls us to develop profoundly new ways of understanding the enterprise of Catholic health care. The challenge applies to both not-for-profit corporations and those with for-profit structural elements. Do our corporate structures embody the vision of Catholic social and economic thought beyond charity care, particularly commitments to the dignity of labor, giving workers a real voice in corporate decision-making, the priority of labor over capital, small pay differentials between associates and senior leadership? As a global church, we in the United States can learn much from imaginative examples beyond our borders. Catholic health in the U.S. could become a leader in innovation, modeling biblical priorities in health care delivery. How might hybrid models be made viable for either parent organizations or subsidiaries as we re-envision health care this post-Affordable Care Act period?

To sharpen the discernment process, we identify the following points:

- Structures matter. Business structures embody assumptions about persons and economic goals — integral human development and the priority of labor, for example. Structures can and should be devised to reflect a theologically grounded vision.

- Catholic social tradition provides a both/and approach to economic analysis; it notes the strengths and weaknesses of market economies. While the church does not reject publicly traded, investor-owned or venture capital structures, its theological commitments point in a direction other than maximizing profits for shareholders. For that reason, the bar must be set high when it comes to choosing standard U.S. investor-owned structures for health care over nonprofit or hybrid structures.

- A prior question about health care as a fundamental good deserves consideration. Papal teaching makes clear that basic human needs ought not be commodified and subject to market dynamics. Is health care one of those "human needs"? If so, does it lend itself to investor-owned models?

- Catholic economic thought, built on the doctrine of caritas, rejects any structure that makes shareholder profits the primary goal. Maximizing shareholder profits is a default rule, however, that shareholders can reject. The articles of incorporation for Catholic health care can specify the primacy of some other goal, as well as the specific ways that surplus revenues will serve those goals. Alternative models can build caritas or the principle of gratuitousness into their articles of incorporation and business practice.

This analysis leads us to examine the ways in which various structures do or do not embody the central theological commitments of Catholic thought. For Catholic health care can advance God's Kingdom in many ways, including civilizing the economy by placing the good of the human community as a higher goal than profit. The foundational question is: Which corporate structures, including new hybrids (some yet to be imagined), best enable laypersons to embody the tradition of caritas in communion? In answering this question, the issue of Catholic identity will find resolution.

KAREN SUE SMITH is a freelance writer, formerly editorial director of America, editor of CHURCH magazine, and associate editor of Commonweal.

QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION AND DISCUSSION CATHOLIC IDENTITY

Catholic identity, who we say we are, should be perceptible to others.

- In what visible ways does your system/facility make its Catholic identity "perceptible to others"?

- How is Catholic identity perceptible in the way people relate to one another in your system/facility?

PRINCIPLE OF MORAL COOPERATION

Benedict XVI said that laypersons should be "regarded as people who are really 'co-responsible' for the church's being and acting."

- In your system/facility is there a spirit of "co-responsibility" for the ministry?

- How is it expressed by executive leadership?

- How is it expressed by all associates?

- Is it felt and experienced by those who receive care?

- In considering and negotiating a new relationship and structure with another entity, through what process would you incorporate a spirit of co-responsibility? With a non-Catholic entity? With a for-profit entity?

THE FOR-PROFIT QUESTION

Within the context of Catholic social doctrine, John Paul II affirmed the priority of labor over capital and of persons over profit and that "work is the primary activity by which persons move toward their fulfillment and advance toward human flourishing."

- How would you address negotiations regarding the work force for a Catholic system/facility that is considering entering into partnership with a for-profit entity?

- As a leader in the process, how do you integrate the concepts of the dignity of the human person and the common good of society into the decision-making process?

"Catholic colleges and universities, health care institutions and social services agencies already live with one foot firmly planted in the Catholic Church and the other in our pluralistic society. .... [Thus, they] face a common dilemma. The bishop and diocese at times may consider them too secular, too influenced by government, too involved with business concepts. The public, on the other hand, often considers them too religious, too sectarian, As a result, they find themselves sandwiched between the church and the public, trying to please both groups ... A mixed model of identity will prevail in the future, not a strictly denominational or secular one.

— Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, "Catholic Institutions and Their Identity," Origins 21, no. 2 (May 23, 1991)