BY: FR. FRED KAMMER, SJ, M.DIV., J.D.

This is the text of a talk Fr. Kammer presented on Feb. 12, 2012, in Washington, D.C. during CHA's Physician Leader Forum. It has been edited to conform to Health Progress style.

It isn't easy to deal with the concept of the "common good," and there are a variety of ways of applying it to the subject of health care and health care reform. I am not promising to make the underlying concept clearer, in the sense of offering a better definition than the classical ones. But I am going to try to frame its underpinnings — look at its "innards," we might say — and suggest some lines of their application to health care and health care reform.

Fr. Charles Bouchard has explained that the roots of the common good lie in Greek and Roman philosophy — common good as the goal of political life, the good of the city and the task entrusted to civic leaders.1 In the medieval period, the common good was seen to be the good of any person, the good of any community and finally the good of God's own self, to whom all creation tends. Lastly, we arrive at the Catechism of the Catholic Church's definition, which is taken from the Second Vatican Council and, ultimately, from Pope John XXIII in his encyclical, Mater et Magistra. According to its primary and broadly accepted sense, the common good indicates the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily.

Again, deferring to the catechism, Fr. Bouchard notes the three essential elements of the common good: Respect for the individual; the social well-being and development of the group; and peace which results from the stability of a just society.

Nevertheless, Fr. Bouchard and several other authors note that the concept of the common good "often remains an abstraction" or lacks realism,2 or is used by the church "as a mantra rather than as a strong analytic tool."3

SEVEN FOUNDATIONAL IDEAS

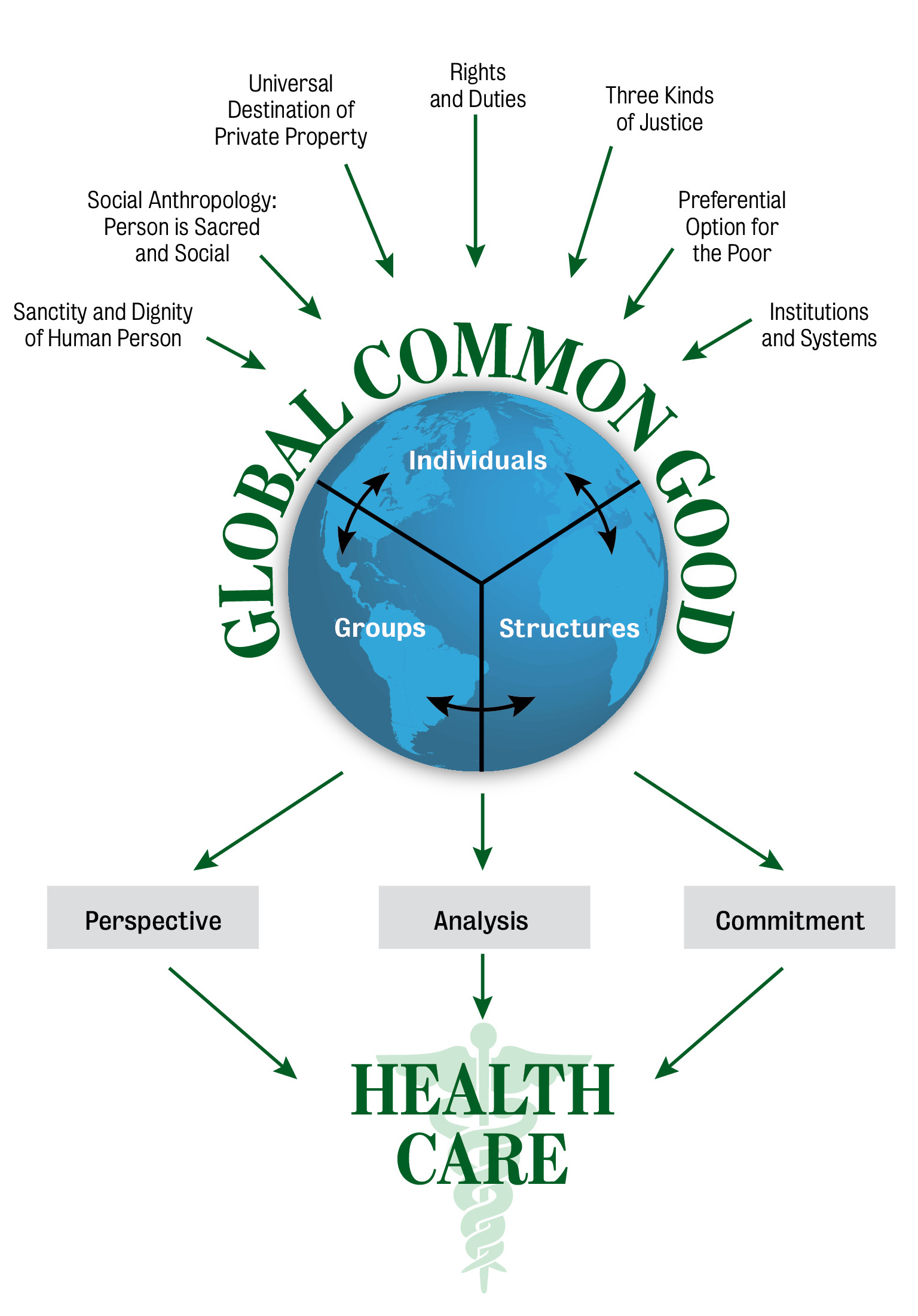

To make matters more confusing, I would like to enumerate seven foundational ideas from Catholic social thought that both help to explain the common good and that give muscle and sinew to the overall skeletal concept. Later, I will enlist Pope Benedict XVI and his very recent discussion of common good to spell out the implications of this understanding of common good. Then I will try to offer three angles on the common good on health care and reform in terms of perspective, analysis, and commitment. The diagram [on page 65] is an outline:

THE SANCTITY AND DIGNITY OF THE HUMAN PERSON

Everything starts here with the creation of the human person in the words of Genesis in the "image and likeness of God" — the foundational concept that underlies all of Catholic social thought. It involves the dignity of the human person that might be found in various secular philosophies or political theories but raised to an incredible level in the belief that the human person is capable of intimate relationship with God and made holy by the grace won by the salvation of Jesus Christ. The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church puts it this way:

A just society can become a reality only when it is based on respect of the transcendent dignity of the human person. … "Hence, the social order and its development must invariably work to the benefit of the human person, since the order of things is to be subordinate to the order of persons, not the other way around."4

This dignity and transcendence does not depend on any accomplishment, any level of education or wealth or membership in any group, race or nation. Likewise, it is not taken away by any birth defect, any disease, any crime or membership in any suspect group. It simply is.

Growing out of the concept of human dignity is an important principle which the tradition calls "subsidiarity," first articulated in 1931 by Pope Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno. It has implications for both the importance of participation and for pluralism. The Compendium puts it this way:

The principle of subsidiarity protects people from abuses by higher-level social authority and calls on these same authorities to help individuals and intermediate groups [families, cultural, recreational and professional associations, unions, political bodies, neighborhood groups] to fulfill their duties. This principle is imperative because every person, family and intermediate group has something original to offer to the community.5

Pope Benedict XVI said in Caritas in Veritate:

Subsidiarity is first and foremost a form of assistance to the human person via the autonomy of intermediate bodies. Such assistance is offered when individuals or groups are unable to accomplish something on their own, and it is always designed to achieve their emancipation, because it fosters freedom and participation through assumption of responsibility. Subsidiarity respects personal dignity by recognizing in the person a subject who is always capable of giving something to others. By considering reciprocity as the heart of what it is to be a human being, subsidiarity is the most effective antidote against any form of all-encompassing welfare state.

Instead of being for or against "big government," Catholic social theory has stressed through subsidiarity that larger political entities should not absorb the effective functions of smaller and more local ones. This was in part a reaction against the centralizing tendencies of socialism and fascism. At the same time, if smaller and more localized entities were not able to cope adequately with a problem or need, then larger entities — the state, for example — have a responsibility to act. Circumstances then determine the appropriateness of "big" or "small" government.

The U.S. bishops later related subsidiarity to "institutional pluralism," such as the role of Catholic health care in the larger world of health care. It provides space, they say, "for freedom, initiative and creativity on the part of many social agents."6 Subsidiarity insists that all parties work in ways that build up society, and that each one does so in ways expressive of their distinctive capacities. This underscores the importance of families, neighborhood groups, small businesses, professional associations, community organizations and local, state, and national government. It also underscores the importance of international organizations to respond to needs and concerns of international scope.

Ultimately, the principle of subsidiarity is rooted in human dignity, in the sense that we are most human and expressive of our humanity in making decisions and solving problems as close to those affected by them as possible. Subsidiarity implies something, as well, about "small is beautiful," environments where persons matter, and participative decision-making.7 As Pope Benedict has made clear in Caritas in Veritate:

… subsidiarity must remain closely linked to the principle of solidarity and vice versa, since the former without the latter gives way to social privatism … .

SACRED AND SOCIAL

Repeatedly the church has emphasized that, in addition to the dignity and transcendence of the human person, that individual person is essentially social in nature. Vatican II put it this way:

Man's social nature makes it evident that the progress of the human person and the advance of society itself hinge on each other. For the beginning, the subject, and the goal of all social institutions is and must be the human person, which for its part and by its very nature stands completely in need of social life. This social life is not something added on to man. Hence, through his dealings with others, through reciprocal duties, and through fraternal dialogue he develops all his gifts and is able to rise to his destiny.8

We all have heard of the need of babies and small children to be held and fondled, that, without such personal attention, touching and care, even the provision of food, shelter, clothing and other essentials still will leave a child severely impaired. The New York Times columnist David Brooks, after extensive time spent with doctors, scientists and others, commented last year on their findings about the human person in these words: "Finally, we are not individuals who form relationships. We are social animals, deeply interpenetrated with one another, who emerge out of relationships."9

In this way, the more recent work of scientists and doctors is deeply consistent with the faith tradition found in the Scriptures.

UNIVERSAL DESTINATION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY10

The church's stance toward private property and, importantly, its concept of the nature of property evolves across the modern tradition. Initially, the popes were strong in their support for the right of private property, though they call upon owners to exercise their own social responsibility in sharing especially surplus property with those in need around them. Gradually, the church stresses a social mortgage on private property. Individual property rights are then conceptualized and affirmed in a socialized context where property must serve the common good and where the state has a duty to insist that it does, even to appropriate it to its common purposes. The right of private property, however, remains intact, especially seen as a way for the poor themselves to acquire and exercise economic rights, freedoms and human dignity.

In keeping with the tradition, Pope John Paul II in Centesimus Annus affirms the importance of the right to private property and the understanding that these rights were not absolute, modified by complementary principles such as the universal destination of all goods. In his own treatment, he roots the common destination of goods in creation and in the Gospel of Jesus and clarifies its meaning:

Ownership of the means of production, whether in industry or agriculture, is just and legitimate if it serves useful work. It becomes illegitimate, however, when it is not utilized or when it serves to impede the work of others in an effort to gain a profit which is not the result of the overall expansion of work and the wealth of society, but rather is the result of curbing them or of illicit exploitation, speculation or the breaking of solidarity among working people. Ownership of this kind has no justification and represents an abuse in the sight of God and man.

Pope John Paul further explains that "ownership morally justifies itself in the creation ... of opportunities for work and human growth for all."

The pope also notes an important development in the nature of property — the "what" — in Catholic social teaching, shifting over the past century from land to capital to know-how, technology and skill. This insight into the nature of property in a highly technical and organized economic society prompts Pope John Paul to a deeper insight into the nature of poverty and marginalization within this same national or international society.

The fact is that many people, perhaps the majority today, do not have the means which would enable them to take their place in an effective and humanly dignified way within a productive system in which work is truly central. They have no possibility of acquiring the basic knowledge which would enable them to express their creativity and develop their potential. They have no way of entering the network of knowledge and intercommunication which would enable them to see their qualities appreciated and utilized. Thus, if not actually exploited, they are to a great extent marginalized; economic development takes place over their heads, so to speak, when it does not actually reduce the already narrow scope of their old subsistence economies.

These people are thus unable to compete effectively or to meet needs formerly satisfied by traditional means of production. Intensification of their poverty, powerlessness and marginalization then results. In his words, "In fact, for the poor, to the lack of material goods has been added a lack of knowledge and training which prevents them from escaping their state of humiliating subjection."

RIGHTS AND DUTIES

In 1891, in Rerum Novarum, Pope Leo XIII built upon the foundational concept of human dignity and the related belief that work is not just a commodity to be bought and sold. From these he developed specific rights belonging to workers: freedom to receive and spend wages as they see fit; to integrity of family life, including provision of necessities to children; a wage sufficient to support a worker who is "thrifty and upright" and, by implication, his or her family. This concept of a family wage was clarified and grew across the 120-year tradition, but its roots are clearly here in Pope Leo's writing and, before him, in centuries of Catholic philosophy and theology.

In a new industrial age, Pope Leo upheld rights to reasonable hours, rest periods, health safeguards and working conditions and special provisions for women and children, including minimum age requirements; freedom to attend to religious obligations; no work on Sundays or holy days; and the right to form workers' associations. Workers also were bound to work well and conscientiously, not to injure the property or person of employers, to refrain from violence or rioting, and to be thrifty and prudent.

Pacem in Terris, written by Pope John XXIII in 1963, was considered to be a kind of human rights manifesto.11 Pope John used reason and natural law to set out rights and duties of persons, public authorities and the world community. He included economic, political and religious rights, immigration rights and the mutual responsibilities of citizens. Pope John introduced the concept of economic rights, drawn from a logical analysis of human dignity. He included the opportunity to work and to do so without coercion, a just wage for the worker and family to live dignified lives, and private property, even a share of productive goods. Pope John's related treatment of the right to life specifically included adequate food, clothing, shelter, rest, medical care, necessary social services and, in the case of sickness, inability to work, widowhood, or unemployment, some form of "security."

This economic rights concept was carried forward by Pope John Paul II in his 1981 encyclical, Laborem Exercens and by the U.S. bishops in their 1986 pastoral letter, "Economic Justice for All." It was also contained in the United Nations' 1948 "Universal Declaration of Human Rights." It implied, as Pope John XXVIII indicated, duties of the state, not just to promote economic well-being, but to engage in positive steps such as providing essential services and insurance systems to guarantee these rights.

In Laborem Exercens, Pope John Paul developed or strengthened a wide range of specific rights drawn from Catholic social teaching. The first was "suitable employment for all who are capable of it," and, when unavailable, the provision of unemployment benefits by employers or, upon their failure, by the state. Just remuneration for work by a head of family must "suffice for establishing and properly maintaining a family and for providing security for its future." This would mean a family wage or other social measures such as family allowances for child-raising mothers.

Pope John Paul taught that there must also be provision of social benefits such as health care, coverage of work accidents, inexpensive or free medical assistance for workers and families, old age pensions and insurance and appropriate vacations and holidays. Trade and professional unions are needed, and the workers retain the right to organize, act politically and to strike "within just limits." The pope affirmed the dignity of agricultural labor, rights of disabled persons to appropriate training and work and the right to emigrate to find work.

The tradition has always combined its assertion of human rights with a correlative set of duties to exercise and/or protect those rights. The Second Vatican Council put it well in its discussion of religious freedom:

In the use of all freedoms, the moral principle of personal and social responsibility is to be observed. In the exercise of their rights, individual men and social groups are bound by the moral law to have respect both for the rights of others and for their own duties towards others and for the common welfare of all.12

For example, I have the right to have a family — then I have a duty to care for them. I have a right to vote — then I have a duty to do it. I have a right to work for a family wage — I then have a duty to do so. I have a right to health care and a duty to care for my health and to make the effort to provide health care for myself and my family, and so forth. And I have a duty to respect and promote those rights that all others have as well.

THREE KINDS OF JUSTICE

Out of our medieval philosophical and theological tradition, the U.S. bishops noted in their 1986 pastoral letter on economic justice the development of three dimensions of basic justice which state "the minimum levels of mutual care and respect that all persons owe to each other in an imperfect world":

Commutative justice calls for fundamental fairness in all agreements and exchanges between individuals or private social groups. It demands respect for the equal dignity of all persons in economic transactions, contracts or promises ...

Distributive justice requires that the allocation of income, wealth and power in society be evaluated in light of its effects on persons whose basic material needs are unmet. The Second Vatican Council stated: "The right to have a share of earthly goods sufficient for oneself and one's family belongs to everyone. The fathers and doctors of the church held this view, teaching that we are obliged to come to the relief of the poor and to do so not merely out of our superfluous goods." Minimum material resources are an absolute necessity for human life ...

Justice also has implications for the way the larger social, economic and political institutions of society are organized. Social justice implies that persons have an obligation to be active and productive participants in the life of society and that society has a duty to enable them to participate in this way. This form of justice can also be called "contributive," for it stresses the duty of all who are able to help create the goods, services and other non-material or spiritual values necessary for the welfare of the whole community. 13, 14

Even these three dimensions of basic justice, the bishops noted, fall short of the goal of biblical justice which portrays a society "marked by the fullness of love, compassion, holiness and peace."15 These aspects of justice, however, are foundational to the common good of any society.

OPTION FOR THE POOR

Our sixth foundational idea is what the church has called the option for the poor, the preferential option for the poor and sometimes a preferential love of the poor. It is a controversial phrase with its roots in the Medellin Conference of Latin American bishops in 1968.16

For some people, the option for the poor is a strong phrase "which has become a powerful summary and symbol of the new approach"17 of the church to the social question. The option for the poor actually reflects Pope John's emphasis one month before the Vatican Council that the church present herself to the underdeveloped world as it is, "the Church of all, and especially the Church of the poor."18

His point has been emphasized again and again by Pope Paul VI, Pope John Paul, and now Pope Benedict. Pope John Paul also used an apparent alternative "a preferential love of the poor." Pope John Paul further restated it as, "preferential yet not exclusive love of the poor," apparently to correct whatever he thought was misleading about the uses of the phrase. Even in doing so, however, Pope John Paul took pains to make it clear that he did not retreat from the point of the preference.19

He himself preached most strongly on this in his travels, including frequent use of Pope John XXIII's phrase "the Church of the poor." In Ecclesia in Asia, Pope John Paul again affirmed this preference and explained it this way:

In seeking to promote human dignity, the Church shows a preferential love of the poor and the voiceless, because the Lord has identified himself with them in a special way (Mt. 25:40). This love excludes no one, but simply embodies a priority of service to which the whole Christian tradition bears witness.

The appropriateness and tenacity of this concept in Catholic social teaching in the past half-century invite us to understand more deeply the concept and its application.

Pope John Paul continued the reflection of the church community on the preferential option for the poor, but with a decided emphasis on the international dimensions of the concern, especially in his 1989 letter, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis:

... the option or love of preference for the poor. This is an option or a special form of primacy in the exercise of Christian charity to which the whole tradition of the Church bears witness. It affects the life of each Christian inasmuch as he or she seeks to imitate the life of Christ, but it applies equally to our social responsibilities and hence to our manner of living, and to the logical decisions to be made concerning the ownership and use of goods.

Today, furthermore, given the worldwide dimension which the social question has assumed, this love of preference for the poor, and the decisions which it inspires in us, cannot but embrace the immense multitudes of the hungry, the needy, the homeless, those without medical care and, above all, those without hope of a better future. It is impossible not to take account of the existence of these realities. To ignore them would mean becoming like the "rich man" who pretended not to know the beggar Lazarus lying at his gate (Luke 16:19-31). ...

The motivating concern for the poor — who are, in the very meaningful term, "the Lord's poor" — must be translated at all levels into concrete actions, until it decisively attains a series of necessary reforms. Each local situation will show what reforms are most urgent and how they can be achieved. But those demanded by the situation of international imbalance, as already described, must not be forgotten.

Pope John Paul makes it clear that the preferential love of the poor has worldwide dimensions and yet touches our most personal decisions. It is rooted deeply in the tradition of the Church, and yet demands contemporary political and economic action.

An interesting formulation of the preferential option was made by the U.S. Bishops in their 1986 pastoral on economic justice: "The fundamental moral criterion for all economic decisions, policies, and institutions is this: They must be at the service of all people, especially the poor."20

INSTITUTIONS AND SYSTEMS

The seventh foundational theme around which revolves the church's reflection in the late 20th century is captured in the following, frequently quoted declaration of the 1971 Synod of Bishops:

Action for justice and participation in the transformation of the world fully appear to us as a constitutive dimension of the preaching of the Gospel, or, in other words, of the Church's mission for the redemption of the human race and its liberation from every oppressive situation.21

Action for justice, then, constitutes part of the preaching of the Gospel. Preaching of the Gospel must give rise to action for justice, or it is simply not a credible Christian gospel. There are two elements here: justice as a part, an expression, of gospel love; and action for justice as a part of our preaching.22

Now here, we encounter another understanding of justice, distinguished from the three kinds of justice that came out of the medieval synthesis and discussed earlier. Justice, however, as used since the 1960s in contemporary church teaching, focuses primarily on economic, social, cultural and political structures. Justice, or the lack of it, manifests itself in the ways in which societies have patterned themselves in institutions, power arrangements, systems of finance and marketing, relationships between classes, ownership of goods and technology and the distribution of costs and benefits among groups of persons. Systemic or structural justice is about those arrangements, patterns, systems and the "ways we do things here."

Not only are these structures real, but in a profound number of powerful ways they shape who we are — shape our living, our loving and our faith. In their pastoral on economic justice, the U.S. bishops stated quite simply: "People shape the economy and in turn are shaped by it."23 Simply stated, this insight reveals that social structures interact with individuals in at least three ways: First, we as social beings structure our lives, usually for good purposes; then, these structures take on a force, power and existence of their own, comparable to ours in many senses; and finally, we are shaped by their existence and power.

Theologians now speak of graced social structures as those which promote life, enhance human dignity, encourage the development of community and reinforce caring behavior. Such entities structure or institutionalize goodness in a way analogous to the good deeds of individuals. Sinful social structures destroy life, violate human dignity, facilitate selfishness and greed, perpetuate inequality and fragment the human community. As such they embody evil in the way sinful deeds do.24

What does this mean? In simple form:

- We have schools that do not teach

- Prisons that do not rehabilitate

- Cities that do not work

- Governments and political parties that are unresponsive to people's real needs

- A food and agriculture system that pays farmers not to grow while many people go hungry

- A health care system that leaves 45-50 million people out, makes some people very rich and often is out of focus in its approaches to human life, happiness, health and dying

- An economic system in the United States and worldwide that is making some people very, very rich and billions of other people poorer and poorer

Not only are the macro-systems not working well, but they are creating extensive injustice, poverty and human suffering across the world. In addition, the repeated and more insistent message of the bishops and popes in modern times is that the situation is getting worse, not better. In fact, the social, economic and political systems are working so badly in many areas that church leaders, such as the bishops gathered at Medellin, have felt compelled to speak of "institutionalized violence" as the end-product of the status quo.25

In Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, Pope John Paul seems at first to accept the analysis of sinful social structures which I have sketched out. His term is the "structures of sin," but his analysis ties these structures much more acutely to the acts of individuals.

...it is not out of place to speak of "structures of sin" which, as I stated in my apostolic exhortation "Reconciliatio et Paenitentia," are rooted in personal sin and thus always linked to the concrete acts of individuals who introduce these structures, consolidate them and make them difficult to remove. And thus they grow stronger, spread and become the source of other sins, and so influence people's behavior.

In footnote no. 65, the Pope lays out four ways in which individuals are responsible for sinful social structures, quoting his earlier apostolic exhortation. (I have inserted the numbers in parentheses for clarity):

Whenever the church speaks of situations of sin or when she condemns as social sins certain situations or the collective behavior of certain social groups, big or small, or even of whole nations and blocs of nations, she knows and she proclaims that such cases of social sin are the result of the accumulation and concentration of many personal sins. It is a case of (1) the very personal sins of those who cause or support evil or who exploit it; (2) of those who are in a position to avoid, eliminate or at least limit certain social evils but who fail to do so out of laziness, fear or the conspiracy of silence, through secret complicity or indifference; (3) of those who take refuge in the supposed impossibility of changing the world and (4) also of those who sidestep the effort and sacrifice required, producing specious reasons of a higher order. The real responsibility, then, lies with individuals. A situation — or likewise an institution, a structure, society itself — is not in itself the subject of moral acts. Hence a situation cannot in itself be good or bad."

Human responsibility is thus retained in Pope John Paul's analysis of social structures. We human persons are still related to all institutions and systems as: (1) creators, supporters, or exploiters; (2) accessories through complicity or indifference; (3) accessories through fatalistic avoidance; and (4) accessories through consecration of the status quo.

If the systems are not working, then our faith response has to be systemic and structural as well as personal. We must do justice as well as charity. It is not enough just to engage in a commendable service that reaches out to help individuals whose lives touch our own, not in the face of massive structural evil that makes these people needy. The faith of those who follow Christ must deal with social, economic, cultural and political structures as well. We must love persons so much that we change the structures that affect their dignity.

Looking at the broader economic scene in Economic Justice for All, for example, the U.S. bishops put it this way:

Whether the problem is preventing war and building peace or addressing the needs of the poor, Catholic teaching emphasizes not only the individual conscience, but also the political, legal and economic structures through which policy is determined and issues are adjudicated.26

Pope John Paul underscores the urgency of connecting action for justice to faith in a term clearly reflecting his Polish background, the duty of solidarity. While not originating with Pope John Paul,27 solidarity includes the structural response demanded by Gospel love. Solidarity involves fundamental economic and social changes.28 In an almost shocking assertion in Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, he says, "Solidarity is undoubtedly a Christian virtue."

Solidarity therefore must play its part in the realization of this divine plan, both on the level of individuals and on the level of national and international society. The "evil mechanisms" and "structures of sin" of which we have spoken can be overcome only through the exercise of the human and Christian solidarity to which the Church calls us and which she tirelessly promotes. Only in this way can such positive energies be fully released for the benefit of development and peace.

This solidarity takes concrete form, the pontiff says, in personal decisions, in "decisions of government", in economic decisions, in public demonstrations by the poor themselves, in sacrifice of all forms of economic, military or political imperialism, and in a variety of other concrete actions, both personal and structural. Solidarity, we are told by the Vatican, will require developing new forms of collaboration among the poor themselves, between the poor and the rich, among and between groups of workers and between private and public institutions.29

GLOBAL COMMON GOOD

This then brings me — "at last," you might say — back to the common good. Only now I want to call it the global common good, in the sense that the common good spans societies from local communities to the so-called "community of nations." I want to start this part with the most recent authoritative church statement on the common good, from Pope Benedict XVI in 2009 in the encyclical Caritas in Veritate. As I do so, I want to highlight what I think are themes or elements of the common good explicit or implied in his text. I have inserted lettered sub-paragraphs in the text for ease of analysis. Otherwise, the text in the original is a continuous paragraph, no. 7. My own explanatory comments are in brackets and italics.

7. Another important consideration is the common good. To love someone is to desire that person's good and to take effective steps to secure it.

[a] Besides the good of the individual, there is a good that is linked to living in society: the common good. It is the good of "all of us," made up of individuals, families and intermediate groups who together constitute society. It is a good that is sought not for its own sake, but for the people who belong to the social community and who can only really and effectively pursue their good within it. [Here Pope Benedict is making the link between individuals, groups and the larger society — which I try to reflect in the diagram in the interconnection of individuals, groups, and structures or systems, my position being that a clearer picture of reality is to see individuals, groups, and larger systems and structures of society.]

[b] To desire the common good and strive towards it is a requirement of justice and charity. [These two foundational virtues lead us to desire the common good.]

[c] To take a stand for the common good is on the one hand to be solicitous for, and on the other hand to avail oneself of, that complex of institutions that give structure to the life of society, juridically, civilly, politically and culturally, making it the pólis, or "city". [Here Pope Benedict is clearly emphasizing the importance of institutions and systems of various kinds in working for the common good.]

[d] The more we strive to secure a common good corresponding to the real needs of our neighbours, the more effectively we love them. Every Christian is called to practise this charity, in a manner corresponding to his vocation and according to the degree of influence he wields in the pólis. [Here again, Pope Benedict emphasizes the roots in charity and also, as in the sentence above, our role as "citizen" — going back to classical thought.]

[e] This is the institutional path — we might also call it the political path — of charity, no less excellent and effective than the kind of charity which encounters the neighbour directly, outside the institutional mediation of the pólis. [The pope's reference to institutions here underscores the three dimensions indicated above.]

[f] When animated by charity, commitment to the common good has greater worth than a merely secular and political stand would have. Like all commitment to justice, it has a place within the testimony of divine charity that paves the way for eternity through temporal action. Man's earthly activity, when inspired and sustained by charity, contributes to the building of the universal city of God, which is the goal of the history of the human family. [This picks up the concept that working for the common good contributes to building what our theology traditionally has called the city of God.]

[g] In an increasingly globalized society, the common good and the effort to obtain it cannot fail to assume the dimensions of the whole human family, that is to say, the community of peoples and nations, in such a way as to shape the earthly city in unity and peace, rendering it to some degree an anticipation and a prefiguration of the undivided city of God. [Here, Pope Benedict makes the point of the importance of the universal or global common good.]

IMPLICATIONS OF THE COMMON GOOD FOR HEALTH CARE AND REFORM

Understanding common good and the seven fundamental themes from Catholic social thought, then, gives more specific content to common good which manifests itself in three "modalities": perspective, analysis and commitment.

- Perspective: I was very taken with the approach of Ron Hamel, Ph.D., in his article entitled, "Of What Good is the 'Common Good'?" There, he took the approach of treating common good as a "lens through which we look at our various worlds." If we do so, he argued, "the concept shapes our worlds, ultimately affecting how and what we see." Hamel called this a perspective, "part of the fabric of our being. Having been internalized, it is simply part of the way we see and approach things."30 Using this approach, Hamel raised several of what he termed "suggestive, not exhaustive" points that such a perspective would have on health care and reform:

Were I a leader in Catholic health care, a concern for the common good would likely direct my attention to the wages and benefits of the organization's employees, to the environment in which and the conditions under which they carry out their responsibilities, and to the degree to which they are able to participate in the decision making and successes of the organization. I might wonder how well my organization not only respects basic rights, but also how well its practices and policies foster an environment in which all employees are respected, valued and affirmed and, ultimately, are able to flourish. Personnel practices and policies would be important in this regard; so would professional development programs.

Looking at patients or residents from the perspective of the common good might lead me to ascertain that all interactions with them respect their dignity, that they receive high-quality care and that they are treated not as isolated individuals but as members of families and other communities. This perspective might also generate concerns regarding an individualistic approach to advance directives, to treatment decisions and to the use of resources.

Finally, a common good outlook would also sensitize me to the local community and its members, to how well their basic needs are being met, to the community and/or societal structures responsible for meeting or not meeting those needs, to how members of the community participate in its goods and life and to how my organization might contribute to the enhancement of the community and its members.31

What Hamel has done in this important interpretation is to alert us to what we might call the instinctual reactions or perceptions of a person who has imbibed the sense of the common good and made it part of their total world view.

- Analysis: I want to suggest now that such a person, under the influence of this ancient and contemporary set of common good values and insights, would want to ask a series of analytic questions that really arise out of the seven foundational insights that have given shape to our understanding of the common good. Using the seven foundational insights, we then might ask the following types of questions about health care and reform:

Re: Sanctity and Dignity: Are the dignity of the people involved — patients, family members, staff, doctors, etc. — respected in the shape and delivery of health care services and care? In keeping with subsidiarity, is individual decision-making respected and encouraged? Are individuals and families educated to deal with their own health needs and growth?

Re: Social Anthropology: Are the relationships of people with one another — in families, work units, laboratories, unions, etc. — respected and encouraged? As Hamel indicated, what is the impact of health care delivery systems and services on the health and well-being of local communities?

Re: Universal destination: To what extent do the health care system and reform plans recognize that the common destination of all goods — including medical care and services, technology, natural resources, the ability to pay and even the human body and its parts — takes precedence over any private claim to ownership?

Re: Rights and duties: Are the individual rights of all those involved respected in the context of their responsibilities for their own care, for others and for the larger common good? Are the rights of employees in health care encouraged, especially the right of participation? Is there a duty of the larger citizenry to sacrifice to insure that everyone can exercise their right to health care?

Re: Three Kinds of Justice: Is there commutative justice in the agreements between payer and payee, workers and management and in the quality of care provided to those seeking medical services? Is there distributive justice in the service of all people, regardless of income and ability to pay? … Is there social justice in the contribution of the entire populace to the health care system and in the respect for the scarcity of health care resources locally and globally?

Re: Preferential Option: Are the poor, the chronically ill, those with disabilities, the frail elderly, those with mental and emotional ills and members of racial and ethnic minorities given special attention in individual care and in the design of the health care system and reform plans?

Re: Institutions, Structures and Solidarity: Do we challenge the systemic aspects of current and planned health systems in ways that speak truth and compassion to entrenched power and greed? Can we contribute to major paradigm shifts in health care services that will encourage preventive health progress, community health benefit, cost restraint, improved quality and access for all? Does the overall design of the health system protect and enhance all seven themes and do so consistent with the global dimension of the common good?

COMMITMENT

Here, I want to return to the concept of solidarity which we discussed under the heading of institutions and systems. What are the implications of that concept, that virtue, in terms of human reaction to injustices of various kinds? Pope John Paul, the foremost exponent of solidarity, ties that theme to action for justice in Sollicitudo Rei Socialis:

It is above all a question of interdependence, sensed as a system determining relationships in the contemporary world in its economic, cultural, political and religious elements, and accepted as a moral category. When interdependence becomes recognized in this way, the correlative response as a moral and social attitude, as a "virtue," is solidarity. This then is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good, that is to say, to the good of all and of each individual because we are all really responsible for all.

In the very next sentences, Pope John Paul underscores the power of sinful social structures as the reason he gives for juxtaposing the powerful virtue of solidarity:

This determination is based on the solid conviction that what is hindering full development is that desire for profit and that thirst for power already mentioned. These attitudes and "structures of sin" are only conquered — presupposing the help of divine grace — by a diametrically opposed attitude: a commitment to the good of one's neighbor with the readiness, in the Gospel sense, to "lose oneself" for the sake of the other instead of exploiting him, and to "serve him" instead of oppressing him for one's own advantage (Matt. 10:40-42; 20:25; Mark 10:42-45; Luke 22:25-27).

When we look at health care in this country (and around the world), as I said earlier, we see a system that now leaves 45-50 million people out, makes some people and organizations very rich and often is out of focus in its approaches to human life, happiness, health and dying. Taking the view of this health care world from those least served and most in need, Christians, in John Paul's view, are then bound to commit themselves to effective action to change the economic, social, cultural and political "ways of doing things" that create and enhance health care injustice. In their place, those who stand with the poor are to erect structures of social, economic and health care justice.

One final word: As we look at the often heated context of the health care reform issues, it is good to be rooted in the virtue of hope — foundational to our religious commitments and often underestimated and misunderstood. It is important to remember the Gospel — that building the Reign of God is about planting small seeds from which great harvests grow and trusting the power of God to turn crucifixion into Easter. My favorite description of such hope came from the Czech poet Vaclav Havel, hero in the struggle against communism in his homeland and later Czech president. In 1986, while his country was still in the grip of communism, he had this to say about hope during a visit to Liberty Hall in Philadelphia:

Either we have hope within us or we don't; it is a dimension of the soul, and it's not essentially dependent on some particular observation of the world or estimate of the situation. Hope is not prognostication. It is an orientation of the spirit, an orientation of the heart …

Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously headed for early success, but rather, an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed.

Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out … It is this hope, above all, which gives us the strength to live and continually try new things, even in conditions that seem as hopeless as ours do, here and now.

— Vaclav Havel, 1986

Fr. FRED KAMMER, SJ, is director of the Jesuit Social Research Institute at Loyola University of New Orleans. An author and an attorney, Fr. Kammer is the former president/CEO of Catholic Charities USA and former provincial superior of the New Orleans Province of the Society of Jesus.

PAPAL ENCYCLICALS CITED IN THIS ARTICLE

Pope Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno (On Reconstruction of the Social Order), 1931.

Pope John XXIII, Mater et Magistra (On Christianity and Social Progress), 1961.

Pope John XXIII, Pacem in Terris (On Establishing Universal Peace), 1963.

Pope John Paul II, Laborem Exercens (On Human Work), 1981.

Pope John Paul II, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (On Social Concerns), 1987.

Pope John Paul II, Centesimus Annus (On the Hundredth Anniversary of Rerum Novarem), 1991.

OTHER PAPAL DOCUMENTS CITED

Pope John Paul II, "Ecclesia in Asia," 1999, apostolic exhortation.

NOTES

- Charles E. Bouchard, "Catholic Healthcare and the Common Good," Health Progress, May-June (1999): 34.

- Lisa Sowle Cahill, "Good News and Bad: As a Source of Inspiration for Healthcare Reform, the Catholic Tradition Has Both Strengths and Weaknesses," Health Progress, July-August (1999): 18.

- Clarke E. Cochran, "The Common and Healthcare Policy," Health Progress, May-June (1999): 41.

- Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Compendium of Social Doctrine of the Church, (2005).

- Compendium of Social Doctrine.

- United States Catholic Bishops, "Economic Justice for All," (1986).

- Philip S. Land, Shaping Welfare Consensus: U.S. Bishops' Contribution (Washington, D.C.: Center of Concern, 1988): 174-177, quoting and responding to Andrew Greeley.

- Vatican Council II, Gaudium et Spes (1965).

- David Brooks, "The New Humanism," Times Picayune (New Orleans), March 12, 2011, B-5.

- Section adapted from Kammer, Doing Faithjustice: An Introduction to Catholic Social Thought (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1991, 2004), 131-134.

- "While it is true that human rights had been defended in previous documents, they had never received such a systemic and thorough treatment. The encyclical was heralded, not for its continuity, but as a breakthrough." Philip S. Land, S.J., Catholic Social Teaching (Chicago: Loyola Press, 1995), 106.

- Gaudium et Spes.

- Excerpted from Doing Faithjustice: An Introduction to Catholic Social Thought, Fred Kammer, SJ (Paulist Press, 1991, 1992, 2004), 78.

- Economic Justice for All.

- Economic Justice for All.

- "Though the precise expression cannot be found in the documents of the 1968 Medellin Conference, there is no doubt that — as the Latin American Bishops stated 10 years later at Puebla — it adopted a clear and prophetic option expressing preference for and solidarity with the poor," Henry Volken, "Preferential Option for the Poor," Promotio Justitiae, 29 (January 1984): 15.

- "For those in favour of the term its main value is that it expresses succinctly and uncompromisingly the practical implication for the Church of committing itself firmly to the promotion of social justice," Donal Dorr, Option for the Poor: A Hundred Years of Vatican Social Teaching (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1983), 209.

- " ... the pope, in a whole series of addresses in 1984-85, was rather chagrined that he could have given the impression of not believing in the preferential option for the poor, or of not believing in it very strongly. To a group of cardinals in Rome, Dec. 21, 1984, he protested:

'This option which is emphasized today with particular force by the episcopacy of Latin America, I have confirmed repeatedly ... I gladly seize this occasion to repeat that engagement with the poor constitutes a dominant motif of my pastoral activity, a concern which is daily and ceaselessly part of my service of the people of God. I have made and I do make this option. I identify myself with it. I feel it could not be otherwise, since it is the eternal message of the Gospel. This is the option Christ made, the option made by the apostles, the option of the Church throughout its two thousand years of history.'

"On October 4 of the same year, he had said to the Peruvian bishops:

'Without doubt, you and your priests know, at first hand, the tragedy of the citizen of the countryside and of the towns of Peru: his very life threatened every day, crushed by wretchedness, hunger, sickness, unemployment; that unhappy citizen who, so often, merely survives rather than lives, in conditions which are subhuman. Certainly such situations respect neither justice nor the minimum dignity corresponding to the rights of man. Reassure fully the members of your dioceses who work for the poor in an ecclesial and evangelical spirit, that the Church intends to maintain its preferential love for the poor and encourages the engagement of those who, faithful to the directives of the hierarchy, devote themselves selflessly to those most in need. That is an integral part of their mission.'

"A few weeks earlier still the Holy Father had affirmed a similar position to the bishops of Paraguay: 'It is true that the precept to love all men and women admits no exclusion, but it does admit a privileged engagement in favor of the poorest.'"

Jean-Yves Calvez, "The Preferential Option for the Poor: Where Does It Come for Us?" in Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits, vol. 21, no. 2, (March 1989): 23-24.

- Calvez, citing a 1980 address of Pope John Paul to the dwellers in the favela of Vidigal in Rio de Janeiro.

- Economic Justice for All.

- Synod of Bishops, "Introduction," Justice in the World, (Rome 1971). This widely quoted section of the document has stirred a lively debate focusing on the word "constitutive." Those not happy with the essential and central nature of justice being asserted for the church have argued that the word "integral" should replace "constitutive" and thus action for justice could take a second place in the church's evangelizing mission to more spiritual or religious matters. See Dorr, Option for the Poor, 187-189 and later. The statement has also been played down by those who hold that the Synods of Bishops are merely advisory to the Pope. Its widespread usage however evokes a power and credence among contemporary Catholic Christians reflecting a kind of sensus fidelium building among both laity and clergy.

- This emphasis is akin to that contained in liberation theology as presented by Gustavo Gutierrez:

"Much more could be said about the theology of liberation as presented by Gutierrez, but it should be clear by now that this is a theology directed toward action in the political, economic, and social spheres. Gutierrez says in his concluding remarks: 'if theological reflection does not vitalize the action of the Christian community in the world by making its commitment to charity fuller and more radical ..., then this theological reflection will have been of little value,' and '... all the political theologies, the theologies of hope, of revolution, and of liberation, are not worth one act of genuine solidarity with exploited social classes.'"

- Economic Justice for All.

- Wesley Theological Seminary professor of biblical theology Joseph Weber describes this reality in these terms:

"The demonic is not an abstract force that can be separated from human existence or from the social and political structures of the world. The demonic forces exist in and through structures. They enter human existence in such a way as to be inherent in human existence." Weber argues that, while a variety of names are used for the demonic forces — principalities, lords, gods, angels, demons, spirits, elements, Satan, and the devil — the terminology all expresses the power of Satan.

- The Latin American bishops: "He [the Christian] recognizes that in many instances Latin America finds itself faced with a situation of injustice that can be called institutionalized violence, when, because of a structural deficiency of industry and agriculture, of national and international economy, of cultural and political life, 'whole towns lack necessities, live in such dependence as hinders all initiative and responsibility as well as every possibility for cultural promotion and participation in social and political life,' thus violating fundamental rights." Second General Conference of Latin American Bishops, The Church in the Present-Day Transformation of Latin America in the Light of the Council (Washington, D.C.: United States Catholic Conference, 1973), section 2.16, 61.

- Economic Justice for All.

- About solidarity: "Solidarity, of course, is not new in the thinking of John Paul II. His 1981 On Human Work used the word frequently enough to cause comment about his explicit support for the Polish workers' movement. But the theme if not always the word is also not new in the previous social teaching of the Church. John XXIII in his 1963 Pacem in Terris spoke of the 'active solidarity' which benefits relations between states, promoting the 'common good of the entire human family.'" Peter J. Henriot, "The Politics of Solidarity: John Paul II's Analysis and Response," in Promotio Justitiae, no. 39, (October 1988): 6.

- Economic Justice for All: "The principle of social solidarity suggests that alleviating poverty will require fundamental changes in social and economic structures that perpetuate glaring inequalities and cut off millions of citizens from full participation in the economic and social life of the nation. The process of change should be one that draws together all citizens, whatever their economic status, into one community."

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Instruction on Christian Freedom and Liberation (1986).

- Ron Hamel, "Of What Good is the 'Common Good?'" in Health Progress, (May-June, 1999): 45.

- Hamel, 46-47.

Copyright © 2012 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.