BY: SANJAY B. SAXENA, M.D., MBA, and TERRY G. WILLIAMS, MBA

For more than 150 years, St. Vincent's Hospital was an important part of New York's Greenwich Village — a place the city's underprivileged knew they could count on for care. St. Vincent's grew into a respected teaching and medical research institution, but financial pressures grew at the same time. In 2010, St. Vincent's survival depended on an investor or a takeover by another New York hospital system. When no suitors emerged, St. Vincent's closed — and New York, a city of more than eight million people, lost its last Catholic hospital.

St. Vincent's problems were unique in the amount of media attention they received, but they were not surprising to other Catholic health system leaders. Catholic health systems are facing challenges all over the United States: Cleveland, for instance, which once had almost a dozen Catholic hospitals, now has only one, and its survival is in question. In Illinois, a number of leading Catholic health systems have undergone significant reinvention.

For Catholic health systems of all sorts, the writing is on the wall. They need to think strategically about their options — and most immediately, about the way partnerships with other organizations, including other than Catholic and non-hospital organizations, can help them recover and thrive.

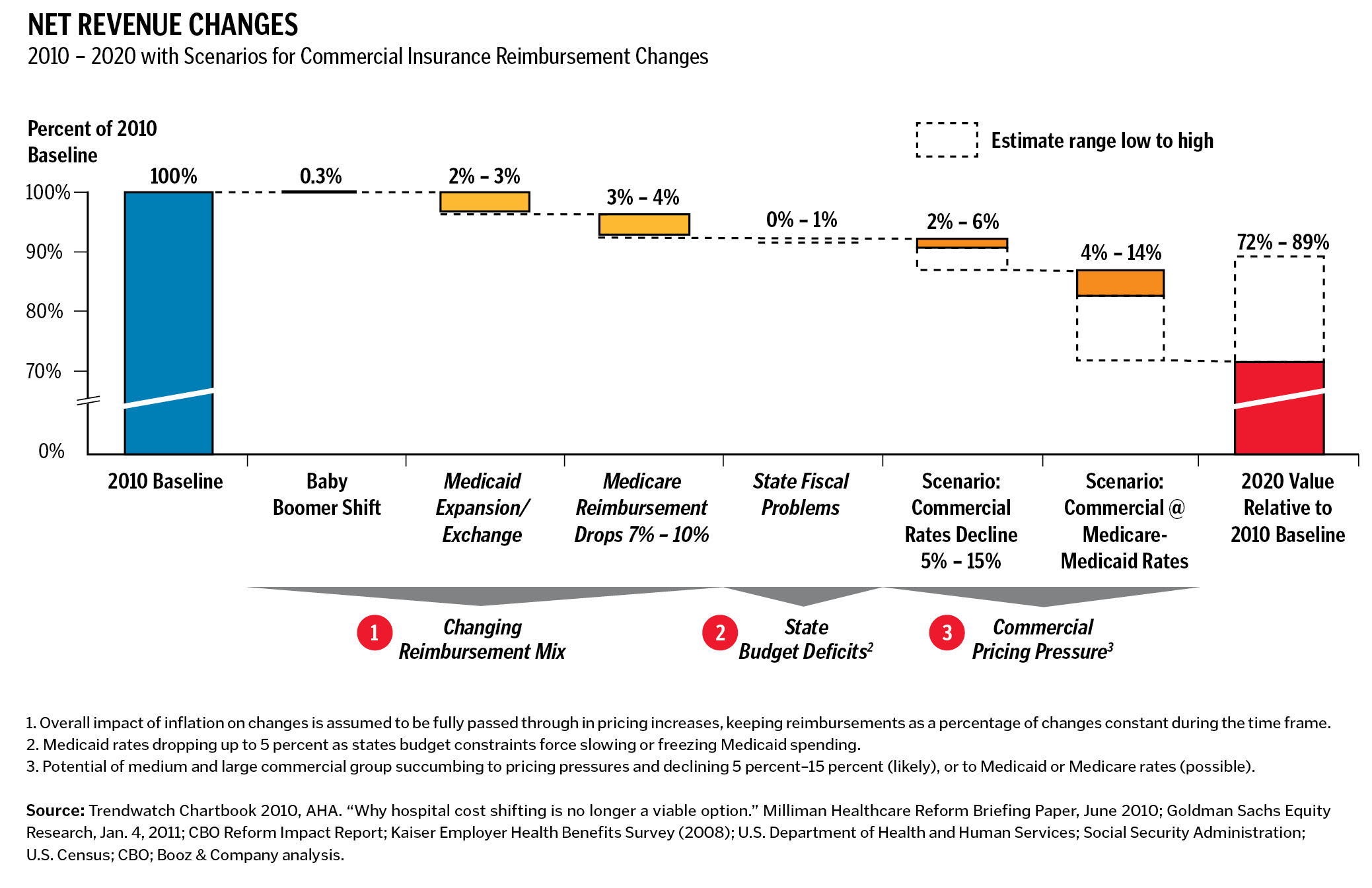

To be sure, Catholic health systems aren't alone in facing headwinds. In May 2012, Moody's Investors Service, citing tightened government requirements and falling reimbursement rates, said it had adopted a negative outlook on the whole nonprofit U.S. hospital sector. A separate analysis by Booz & Company suggests that by 2020, hospital reimbursement rates nationally will decline by as many as 28 percentage points versus 2010 levels. Moreover, with some states facing severe fiscal problems, it's hard to see how any hospital, in any geography, will avoid the pinch.

But Catholic hospitals face special challenges because of the number of poor and uninsured patients they serve. Their mission leads Catholic hospitals to stay in many geographic areas that other hospitals have fled since the 2008-2009 recession. This leaves Catholic hospitals bearing a disproportionate share of the burden from states' fiscal problems and the associated cuts in Medicaid and social services. And then there are the additional financial pressures brought about by meaningful use requirements and by the shift to population management and accountable care organizations (ACOs). While these new models of health care may well end up being more efficient, they have near-term uncertainties and investment requirements that many Catholic systems can't readily handle.

Given the pressures, it's no wonder that so many Catholic health systems have sought scale by merging with other hospital systems. The mergers generally fall into three categories: within-faith mergers of equals; within-faith acquisitions of local health systems by regional or national ones; and the increasingly common mergers with other than Catholic health systems. Illinois, where we happen to spend a good deal of our work lives, furnished examples of all three last year in the Chicago area. Presence Health itself (which resulted from the union of Provena Health and Resurrection Health Care) is an example of two locals merging to form a super-regional across the state, and Ascension Health's acquisition of Alexian Brothers Health System is an example of a national Catholic system buying a local one. As we write this, the third type of merger is also in the works, with Chicago's Holy Cross Hospital negotiating to become part of Sinai Health, a Jewish hospital system across town. Elsewhere, the challenges of Catholic hospitals have started to capture the interest of private equity investors, as was evident in 2010 when Cerberus Capital Management bought Caritas Christi Health Care, a hospital system in Massachusetts.

These mergers face challenges that go beyond the inevitable post-merger integration issues — like the need to standardize around one health system's technology, and the possible loss of local control. Certainly with the other than Catholic mergers, an additional question is the fate of the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (ERDs) that have traditionally shaped Catholic systems. For example, the recent would-be merger between Catholic Health Initiatives (CHI) and publicly funded University Hospital in Louisville was blocked by Kentucky Gov. Steve Beshear, who said it would keep women from getting contraceptive services. Indeed, conflicts relating to the ERDs have created challenges for Catholic health systems outside of merger situations. As a result, some players, such as Catholic Healthcare West (CHW) of San Francisco, have decided to alter their organizational structure to more readily accommodate other than Catholics, as signified by CHW's 2012 renaming to Dignity Health.

That so many Catholic systems remain in the hunt for a merger partner, despite the difficulties, is a sign of how critical the situation has become. Mergers can create more attractive networks and scale with payers and more access to capital. In some cases, they are a necessary condition for survival. We're just not sure they are sufficient anymore.

NEW PARTNERSHIP PARADIGMS

All hospitals and health systems, Catholic ones included, are at a stage where they should be thinking about new kinds of partnerships besides mergers. What's important is that the new partnerships give Catholic health systems access to capabilities that are going to be critical to the future of health care. Here's a look at the who, what and why of five new partnership types, starting with the most straightforward to implement.

- Shared services partnerships. These partnerships provide scale and capabilities without the loss of local control. The capabilities can be ones the hospital hasn't developed on its own, such as population analytics, certain types of specialized care or back-office functionality. A number of such partnerships are already underway. This spring, for instance, CHI, a faith-based system based in Englewood, Colo., with a presence in 19 states, entered into a revenue management deal with Conifer Health Solutions of Dallas for 56 CHI hospitals. Conifer, a unit of for-profit Tenet Healthcare Corp., also headquartered in Dallas, will help CHI off-load revenue management at a time when the changing health care and reimbursement landscape is making that task increasingly complex. Another example of a shared service partnership is Aetna's plan to implement health information exchanges for Banner Health. Hartford, Conn.-based Aetna had previously formed an ACO with Banner, a hospital system headquartered in Phoenix that Aetna is paying based on how healthy it keeps its patients.

- Partnerships with physicians. This is another type of partnership that will likely require big adjustments in order to achieve the promise. Traditional physician relationships have not given physicians much incentive to help hospitals succeed in the areas of value-based purchasing, shared savings programs and bundling of services. For example, physicians often demand that hospitals buy the newest and most expensive equipment, even when there is no conclusive evidence that the technology improves patient outcomes or is cost-effective. In an era of ACOs and bundled payments, physicians need to become a partner in the development of higher-quality, lower-cost medical care options. The challenge is figuring out how to structure the partnerships so that physician and health system incentives are in alignment. Physicians need not be employed by the health system partner in order for these arrangements to work; legal options such as co-management and clinical integration offer viable alternatives. In particular, successful clinical integration may require other types of partnership to provide access to aggregated patient data, clinical best practices, population management analysis and care management capabilities.

- Partnerships that expand community access. Health systems have alternatives for accessing patients and managing population health that fall outside the traditional model of physician-patient care in a doctor's office or clinic (and the even more costly practice of patients using the emergency department for non-emergent care). For instance, hospitals in a number of states, including Georgia and Tennessee, have partnered with CVS Pharmacy MinuteClinics, staffed with nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Likewise, hospitals in other states such as Louisiana and Florida have formed relationships with Walgreens' Take Care Clinics, which offer many basic medical services and have the potential of improving population health. With other major retailers like Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Target increasing their presence in the convenience-care market, the role of retail clinics will continue to expand as awareness and use among consumers accelerates.

As for Catholic hospitals, they have another ready-made community access point — houses of faith themselves. We have seen health care organizations use church facilities to conduct screening and training to improve population health (sometimes right after Sunday services). In Detroit, for instance, which has one of the highest poverty rates among big U.S. cities, the Henry Ford Health System has installed interactive kiosks from which church congregations can get information about medical topics and healthy living. Another community health organization in Detroit, the Joy-Southfield Health and Education Center, grew out of a mini-clinic for uninsured residents in the basement of a Methodist church and now partners with educational institutions and other experts to deliver health education classes and disease management programs.

- Partnerships with government entities. This type of partnership has particular relevance to Catholic health systems because of the help such partnerships could offer the poor, including Medicaid patients. By partnering with the government, Catholic hospital systems could get access to population patient data — often hard to come by, with patients who may have no consistent home address or job but who generally turn to the government for food subsidies, unemployment checks and Medicaid cards. When they have access information, health care systems have a better chance of contacting patients and of getting them to follow preventive health protocols. A partnership with the government may also lead to an exclusive territory, allowing Catholic hospitals to recover in volume some of what they may be losing because of rate decreases.

Partnerships might also be put in place to cut the costs of treating Medicaid patients (who come with all sorts of burdensome restrictions), or to allow a Catholic health care organization to manage a portion of a state's Medicaid requirements. Effective strategies for dealing with the potential "church and state" issues — as well as women's health requirements — need to be developed in advance of any such partnerships.

- Partnerships with payers. This is one of the most crucial types of partnerships to explore — and the trickiest. Traditionally, there has not been a lot of trust between hospital systems and insurance companies. The business model around population management — in which a portion of the savings achieved in treating a population flows back to the hospital system and payer — offers the hope of changing this dynamic. Hospital-payer partnerships make particular sense in situations where the payer has experience with, and data on, a population — such as people over age 70, people with diabetes or people who work for a specific organization.

Indeed, one attractive characteristic of payers — from the perspective of Catholic health systems — is their ability to provide capital for the development of new services. Areas of possible joint investment include virtual technologies (to reach areas underserved by physicians), health information exchanges (to allow different electronic medical record systems to talk to each other) and co-development of community access points (to address areas of unmet need).

A big question in Catholic health systems' ability to move toward these types of relationships is the readiness of payers. Some payers, it's true, have demonstrated the right DNA for a progressive partnership. Others are tethered to the typical negotiated fee, whether for a population or a discrete medical procedure; these payers tend to prefer an assured outcome to shared risk and the possibility of a shared upside. In these situations, it's hard for a different kind of partnership to take root.

Of course, the reluctance is not always on the side of the payer; there are some Catholic health care systems that aren't yet comfortable with the idea of anything other than traditional negotiated fee-for-service relationship. And then it is the payer, not the health care system, that is likely to be stymied in its quest for something new.

WHAT CATHOLIC HEALTH LEADERS MUST DO

The mission of Catholic health systems — including delivering care to the needy —remains vital. To fulfill it, however, Catholic health system leaders are going to have to be smart and creative about the next phase of their organizations' lives. The imperatives for Catholic health care systems in the next few years should be to:

- Tally the health and health-related services that are available in each community served, clearly defining the community's needs while avoiding unnecessary duplication of efforts

- Take a hard look at the full spectrum of services they provide, to be sure they have an effective and economical solution

- Get comfortable with the idea that reform requires new domains of expertise and that forging new relationships, and soon, may be required to remain competitive

- Focus on relationships which enable a more seamless, less siloed, more consumer-centric system

- Avoid partnerships in which being Catholic will create obstacles that are difficult or expensive to overcome

- Consider early the governance and sponsorship implications of the new relationships they do choose to forge.

SANJAY B. SAXENA is a San Francisco-based partner with the global management consulting firm Booz & Company and co-leader of its North American Hospital & Health Systems practice.

TERRY G. WILLIAMS is chief strategy and growth officer at Provena Health-Resurrection Health Care, now called Presence Health, in Chicago and Mokena, Ill. Presence Health is Illinois' largest Catholic health system.

FAITH NOT A FACTOR IN HOSPITAL SELECTION — BUT VALUES ARE, PATIENTS SAY

Contributing to the challenges faced by faith-based hospitals is the fact that relatively few people cite a hospital's religious affiliation as a reason to go to it.

Consistent with prior CHA studies, market research by Presence Health revealed that only 10 percent to 15 percent of individuals chose their health system because of particular religious affiliation. Insurance coverage, reputation and the recommendation of a medical professional were all more important.

On the other hand, the values of Catholic health care, including treating people with compassion and respect, caring for families as well as focusing on the whole person, not just the disease, are values that patients frequently cite as important to them.

Copyright © 2012 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.