BY: SR. KATHLEEN POPKO, SP, PhD; SR. JOAN MARIE STEADMAN, CSC, MA; and MELANIE DREHER, RN, PhD

Illustration by: Nancy Stahl

Language is important in how we describe our relationships and our work. The words we use are key to communicating effectively who we are and what we are about. Language has the power to influence and shape our values, attitudes, prejudices and behaviors.

The language of consumerism is now flooding the health care field. This raises questions about its potential to erode in subtle ways the faith-based mission and values that undergird the Catholic health care ministry.

The United States frequently is characterized as a consumer society. Such a society often uses resources without reflection and discernment about the implications of the patterns of consumption.

The current emphasis on consumerism deserves attention, not only because the consumer-focused language is gaining traction within nonprofit health care, but also because there seems to be the growing expectation that the "consumer-focused" model of health care is "the future delivery system." Catholic health care boards and management need to be attentive to this cultural change and reflect on its implications.

The literature is replete with descriptions about tectonic shifts in health care that are driving changes in care delivery:

- Increasing cost pressures on providers

- Increased price sensitivity for patients seeking the best value

- Increased innovator/disruptor impact

- Increased concern about affordability and access

These shifts often are described in terms of consumerism. It's not uncommon to hear phrases like:

- Disruptive innovators are investing as they see opportunity in health care delivery to create value for consumers and earn profit.

- Consumers are seeking providers that offer a new standard of value based on convenience, access and transparency.

- Retail clinics and urgent care sites are said to offer convenience, access and cost transparency to consumers.

Some of us engaged in Catholic health ministry have concerns about the implications of adopting the language of consumerism and the behaviors and decisions that flow from such a consumer-focused approach.

Why would Catholic health ministries' efforts to make treatments easier, less costly and more convenient for those we serve be called consumerism instead of truly person-centered care? For example, the attempt to transfer routine health care from hospitals to less expensive venues and less costly providers is not consumerism. It is what we need to do if our motivations for doing so correspond with our person-centered values. Creating a better experience for our patients and using technological innovation is what we should be doing; and if it provides health care that is more cost-efficient, it is good for society. Similarly, access and transparency always have been important to us, especially for people who are vulnerable.

There are two different but related interpretations of consumerism. The first, which emanates from economic theory, suggests that increasing consumption of goods is economically desirable. This is linked to a preoccupation with and an inclination toward the buying of consumer goods.

Such a definition of consumerism creates a challenge for Catholic health care because our focus is to be a ministry of healing, responding to the health care needs of people and communities, not promoting consumption.

The second interpretation of consumerism centers on promoting and responding to "consumers' interests." Most Catholic health care providers would resonate with such an approach, but use the language of patients' or clients' interests.

DIGNITY OF THE PERSON

The concept of the person as a consumer reflects a broader cultural shift that has the potential to be dehumanizing and to undermine the goal of person-centered care. Consumers are viewed in economic terms related to their ability to purchase a product. Those selling a good or service are challenged to find ever-new ways to entice the consumer to "buy" what they offer and to create the perception that it is better than what a competitor is offering.

The use of the word consumer is inadequate to describe a person seeking health care. Persons in need of health care are seeking not a product to be consumed, but a necessary service, ideally to restore well-being. If we believe that health care is a human right — not a product to be consumed — it is a service to be provided to all without regard to their financial status and the ability to purchase the product/service. Persons who lack financial resources are already at risk of not receiving the necessary health care services they need to thrive. As the concept of the person as a consumer becomes more and more a part of thinking and planning, will this contribute to a further erosion of the delivery of health care services to persons on the margins — to those who cannot participate in this evolving competitive health care marketplace?

Such an approach seems inconsistent with the commitment of nonprofit health care to keep people well and to do everything possible to limit overuse of services, such as emergency rooms, unnecessary diagnostic procedures and medical treatments.

WHY CHANGE LANGUAGE?

A further, basic question asks why Catholic health care may be moving in the direction of adopting the language of consumerism. Interestingly, many other comparable service sectors, like education, religion, law, tourism, finance, police and fire protection, do not define the objects of their enterprises as consumers, although there is nothing to prevent them from doing so. Nor do they use the term consumerism to describe the many disruptive innovations, changes and technological advances that permit them to provide service and generate greater revenue. Despite the profound impact of technology on education, it has not redefined students as consumers; law still views its users as clients; the travel industry still refers to the users of their services as passengers and travelers.

So why is the language of consumerism finding its way into Catholic health care? Perhaps there are a few reasons that collectively are drawing us in this direction:

Insurance: As payers shift financial responsibility to patients through high-deductible plans, patients are behaving more as consumers, i.e., price-conscious buyers who are expecting their experience with health care providers to mirror those in the retail market.

Democratization of medicine: Patients have been empowered through the democratization of medical knowledge. They seek information online and may approach their physicians with detailed information, which changes the typical dynamic with their medical doctor. Patients are seeking more voice and greater involvement in their care. The patient-physician relationship is being redefined.

Increasing outpatient services: There has been a major shift to provide outpatient services in a variety of settings such as urgent care, surgical, birthing and sports medicine centers, where competition is heightened with a myriad of physician and for-profit competitors. New and innovative entrants to health care are disrupting and challenging traditional providers. Adoption of for-profit marketing approaches seems to be part of this disruption.

Catholic health care leaders acknowledge the need for heightened attention to patients/clients' preferences for convenience, access and transparency. However, there is a deeper concern, which relates to the adoption of language and moves the Catholic health care ministry into the realm of retail consumer culture and portrays health care delivery as a transaction between a buyer and seller, as it would treat any commodity.

LANGUAGE REINFORCES VALUES

The mission of Catholic health care is built on the bedrock of the dignity of every person. Healing, and the journey toward wholeness, take place within a trusting relationship and within a community of caring. Focusing on the care of the whole person — mind, body and spirit — challenges everyone serving in the ministry of Catholic health care to provide an integrated, holistic approach to healing.

The influence of a culture that views the person as a consumer in an economic model has the potential to reduce the health care relationship to a transaction, shifting the focus from service to a person to delivery of a commodity. The language of some providers is telling, with talk of the focus on "health care as an easy shopping experience" and reference to "consumption patterns to fit a preferred solution."

In this rapidly changing health care delivery system, focus on convenience, quality and reasonable cost for services demands close attention from all engaged in the ministry of Catholic health care. We must discern ways to bring high quality, accessible and affordable health care to the heart of the communities we serve — communities that span the spectrum of available economic resources and access to health care services. Available to all, our health care settings need to be seen as places of healing, our staffs as part of a community of caring.

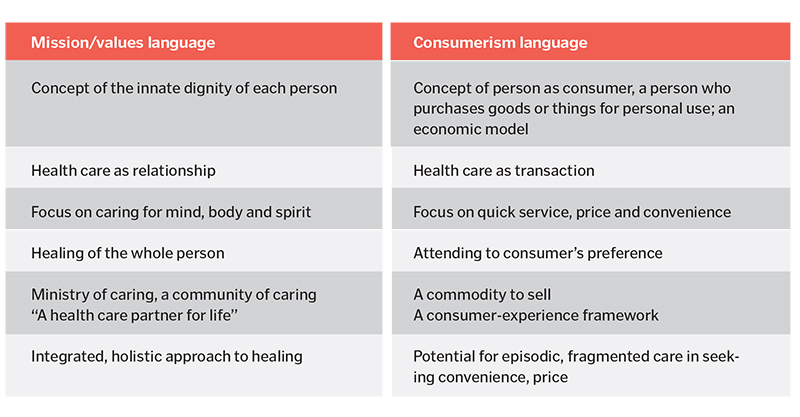

The chart below displays the contrasting tension between the language of mission/values and the language of consumerism.

From a ministry perspective, the language of consumerism could come to undermine our strong conviction that mission-driven health care is a ministry of healing, not simply a business selling a commodity or service. Catholic health care clearly intends to be more. Following Jesus' approach, health care is an encounter with persons at their moments of greatest vulnerability, with life and death, with pain and loss, with recovery and return to health. Decisions made or not made have lifelong consequences, not only for the person, but also for loved ones, family and colleagues. This is a deep level of engagement, based on relationships of trust.

From the perspective of patients, a trusting relationship with the caregivers (far beyond a transactional relationship) is a high priority in whatever the setting. Caregivers guide patients through their journey; they take the time to discover individual patients' needs and goals; and they explain how the course of treatment is consistent with those goals. Members of the care team then communicate with the patient, the patient's family and one another as to how these goals will be integrated into the professionally designed care plans.

Catholic health systems and hospitals have made major commitments and investments integrating Catholic mission and values throughout the ministry. This is critically important because the words we use impact our identity, how we speak about ourselves and, ultimately, our thinking and behaviors. The language of consumerism does not touch our deepest understanding of the mission of Catholic health care -- who we say we are and what we are about.

We strive to keep in the forefront the healing ministry of Jesus, our mission and core values, and our commitment to give new expression to the legacy of the founding religious orders. We create and provide formation experiences for sponsors, trustees, management and all colleagues in every part of the organization. We develop processes and procedures for discernment on issues of business and clinical ethics that are rooted in our mission and core values.

A CALL FOR REFLECTION

Leaders in Catholic health care may wish to pause and to reflect on the influence of the language of consumerism. Here are some timely questions for consideration. They are intended to encourage dialogue between and among board members and management, to raise awareness, explore implications and take appropriate action.

Have we already adopted the language of consumerism? Are we unreflectively or unconsciously shifting our focus from person-centered to consumer-focused language? If so, what are the implications?

Do our presentations, strategic plans, priorities and budgets incorporate this language? If so, what are the implications?

Could the language of consumerism erode our focus on the community, on population health, on addressing pressing needs in the community through building relationships and partnering with other organizations? If so, what are the implications?

How can we avoid the trap of complacency that tells us language does not matter or will not affect the living of our mission and core values?

If we believe that language shapes and expresses our values, attitudes and behaviors, individually and collectively, we must engage the challenge that the language of consumerism presents. Through our reflection and thoughtful actions, we can be countercultural, perhaps even influence the broader culture. In all we do, we will maintain that health care, at its core, is a human encounter, a trust relationship, and not simply a transaction based on convenience and price.

Catholic health care for centuries has centered on the dignity of each person and the compassionate care that each person should receive. In our times, the language we use is a continuing sign of Catholic health care's commitment to be person-centered.

SR. KATHLEEN POPKO, SP, is president of the Sisters of Providence, Holyoke, Massachusetts; previously she was a member of the Catholic Health East senior management team for 12 years. SR. JOAN MARIE STEADMAN, CSC, serves on the National Advisory Council of the Saint John Vianney Center in Downington, Pennsylvania, and also advises the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University in California. MELANIE DREHER is a nurse anthropologist, researcher and educator. All three authors are members of the Trinity Health Board and its ministerial juridic person, Catholic Health Ministries.