BY CHARLES E. BOUCHARD, OP, STD, and ALEC ARNOLD, PhD(c)

Illustration by: Jon Lezinsky

We are in the midst of an unprecedented public health crisis that is changing our personal lives, our economy and our health care system. This is particularly true of elder care, which has been described as "ground zero" for the COVID-19 virus.1 The COVID-19 pandemic did not cause the crisis in long-term care, but it did exacerbate it and expose many of its latent flaws. Society as a whole must face this problem, but we believe that sponsors in Catholic health care should ask themselves whether a crisis of this magnitude is a call to rethink their role and their responsibility.

DECLINING CATHOLIC INVOLVEMENT IN ELDER CARE

Changes in the delivery and funding of elder care have long been in order, but the spotlight recently shone on the vulnerability of so many of our elders underscores the need for radical transformations. Bill Thomas, a famous innovator in long-term care, said in a podcast that "this pandemic will change long-term care forever — inside and outside." He said the consequences are like "flipping the game board," and starting all over.2 If the board is flipped, we want to ask: as the pieces are reassembled, where will the Catholic role in elder care fit?

There are some outstanding Catholic long-term care ministries, including Benedictine Health Service, Carmelite Sisters of the Aged and Infirm, Franciscan Ministries and Trinity Health's extensive PACE program. Their stories show what quality care looks like and also that quality care is achievable, even with our current payer mix. But our presence is much less than it used to be.

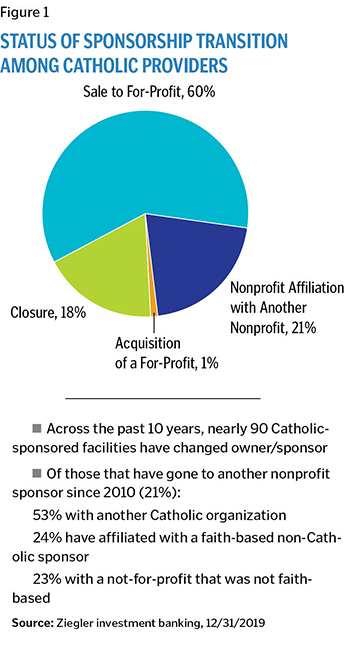

Catholic systems and sponsors have steadily divested themselves of long-term care and continue to do so. According to research conducted by the investment firm Ziegler, over the past decade there have been 90 Catholic-sponsored facilities that have converted, at least 70 of which either sold to a for-profit entity or closed entirely. Of the remaining transitions, only about half (or 11% of the whole) affiliated with another Catholic organization.3 Given the difficulty in tracking every shift of ownership or management across various systems, such data has its limits; and yet public announcements about ministries in transition continue apace. The Little Sisters of the Poor recently initiated plans to phase out of their long-term commitments in Richmond, Virginia, (where they have served since 1874) as well as in San Pedro, California.4

In short, while a number of things contributed to our current situation, the diminishing presence of Catholic elder care is cause for concern (see Figure 1).

FINANCIAL ISSUES AND CARE QUALITY

Long-term care as we know it today started with the establishment of Medicaid and Medicare in the 1960s. For many of the nation's elderly, such programs were an improvement over board and care facilities (residential group homes that often don't have nursing and medical care on site), but they were never intended to support a comprehensive array of elder services nor to provide for impoverished middle-income seniors.

Changes related to Medicaid and Medicare concretized a "nursing home model" of care, defined by institutional provision of skilled nursing alongside long-term residential services in licensed facilities, such that alternative arrangements (such as family-supported, home-based care) fell outside the scope of coverage.5 Nursing home chains soon emerged as the monolithic provider of elder care, with private equity and for-profit investors steadily absorbing most of the market.6

The investor model became predominant because of a strategy that focused more on real estate than health care. This was possible because often the property on which a care facility was located was more valuable than the services taking place therein. One report describes how this worked.

"Investors created new companies to hold the real estate assets because the buildings were more valuable than the businesses themselves, especially with fewer nursing homes being built. Sometimes investors would buy a nursing home from an operator only to lease back the building and charge the operator hefty management and consulting fees. … [They] also pushed nursing homes to buy ambulance transports, drugs, ventilators or other products from other companies they owned."7

This enabled the facility itself to show a respectably thin profit while the parent corporation made money through the management company.

This arrangement is eerily reminiscent of the business model that Ray Kroc developed for McDonald's in the 1950s, portrayed in the movie "The Founder," starring Michael Keaton. There is a scene in which Kroc realized, with the help of a savvy finance guy named Harry Sonneborn, that he could make far more money by leasing than franchising. Sonneborn tells him, "You're not in the burger business, you're in the real estate business. You don't build an empire off a 1.4% cut of a 15-cent hamburger." And the rest is history. Today there are just about as many McDonald's as there are nursing facilities.8

It is not hard to see how some of the same strategies led to the acquisition of so many long-term care facilities and that these acquisitions did not always serve the best interests of residents. Along this line, Charlene Harrington of the University of California San Francisco led a 2011 study examining the quality of care provided by 10 companies responsible for an aging population that amounted to about 14% of all American nursing home residents.9 The study found that for-profit nursing homes were more poorly staffed and had greater deficiencies than other providers.

More recently, researchers examined the question, "Does Private Equity Investment in Healthcare Benefit Patients?"10 Using evidence derived specifically from nursing homes, the short answer was no. When private equity gets involved, care suffers.

The problem is obvious if you observe that most nursing homes operate according to a notoriously problematic business model, which hangs on getting the right mix of private pay, Medicaid and Medicare funders. Medicaid pays facilities much less to attend to their long-term residents than Medicare will pay for short-term rehab patients. Short-term patients with higher billable care are needed to compensate for the less lucrative long-term residents. On average, the mix of long-term residents to short-term patients is in the ballpark of 87% to 13%.11 This means the majority of beds are draining the provider of money, while 13% of the beds — used for those short-term, post-acute patients in rehab or recovering from illness — are responsible for financial viability.

In the past, private payers helped the dynamics of the spreadsheet, but in recent years, many people with the capacity to pay have opted for other arrangements. The longer and healthier lifespan of the boomer generation is inspiring major changes in the way elder care is conceived, arranged and accessed.

For the poor and vulnerable, however, too few options are available. As COVID-19 has made clear, the aging poor are dangerously dependent on a system structured to prioritize its own financial interests over the care of patients.12

CONCEPTUAL PROBLEMS

In addition to these financial issues, there are also conceptual problems. For example, we don't even know what to call whatever is not acute care.

In the past the nursing home (or just "the home") was the place you went when acute care could do no more for you. Many people still see it as the place they never want to be. Yet elder care today encompasses a wide variety of services ranging from true long-term, skilled nursing care, to assisted living, to PACE programs, to "high acuity assisted living" ("aggressive symptom management in patient's preferred setting") to short-term rehab care, which often takes place in the same facility as long-term care.

Nursing homes now exist alongside life plan communities, adult day care, affordable housing options, freestanding memory care centers, and assisted living and home health programs that enable "aging-in-place." Rather than focusing strictly on skilled care at the end of life, many advocates have been working to realize a vision of aging that is sufficiently comprehensive while being driven by deeper values than those of the market alone. As a case in point, LeadingAge has an illustrious history of organizing collaborative relationships among nonprofit elder care providers, for the sake of finding creative solutions to a wide range of problems in the quality and accessibility of care.

Nevertheless, a conceptual distinction persists between the acute care setting and the elder care context—even though, paradoxically, nursing homes are still viewed and often managed as "little hospitals." The president of the Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine recently pointed out that "hospital systems really do not know that much about the nursing environment," and that hospital-based providers "keep on forgetting" that nursing homes are "not mini-hospitals."13

The prevalence of this hospital paradigm has limited the creativity that would lead to truly effective and comprehensive senior care.14

Long-term care also suffers from an image problem, which no doubt contributes to its funding problems. It is easy to celebrate a high-specialty children's hospital where smiling children are discharged after surgery or chemotherapy to treat a brain tumor. Long-term care has less media appeal. Recent deaths arising from the COVID-19 crisis have made things even worse. And yet, would anyone argue that the child is less vulnerable or more valuable than an aging senior?

A number of efforts have already been underway, aiming to reconceive what long-term care can look like in the future. The goal will extend beyond housing and medical care, but will manage what Msgr. Charles Fahey, a pioneer in long-term care, describes as "progressive intermittent frailty," in a variety of settings.

Notable bright spots here include CHA's partnership with The John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Hospital Association and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in the Age-Friendly Health System initiative, geared to improving patient care policies,15 and The Pioneer Network, organized in 1997 to change the culture of aging from a medical, institutional model to a person-centered model. Bill Thomas's work on the Green House Project and the Eden Alternative do the same thing by different building design and a range of educational and training programs to put residents first.

Thomas says that "good health care is necessary, but it is not enough. Long-term care needs to be integrated into the health care system" rather than seen as an auxiliary enterprise.16 Home health care will also play a bigger role. Thomas says that in the future we are going to see "home and health care blended in surprising ways."17

Indeed, we have not yet integrated many elements that are already at hand. Newer specialties, like hospice and palliative care, are still often stand-alone programs that have not been integrated into acute care or long-term care. Spiritual care, which could help bridge the gaps between acute care, palliative care and hospice, is often neglected in favor of medical solutions. As one commentator notes wryly, in addition to providing "real medicine and real nursing, that deal with real problems," we also have to deal with "that other 'squishy stuff' like loneliness, helplessness and boredom."18

POLICY REFORM

COVID-19 poses several immediate challenges. Legislators and policy makers at the federal level must focus on the various problems related to COVID — inadequate testing, lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), medicine and space. These things require funding as well as effective management. Our failure in both areas is painfully obvious right now as seniors and their families suffer anxiety and loss. Those of limited means are at even greater risk.

Reorganizing health care in a way that improves elder care, integrates it with acute care, palliative care and hospice and lowers cost is an enormous long-term policy challenge. In a recent interview with Senior Housing News, Ascension Living CEO Danny Stricker talks about all of these problems and makes some policy recommendations as well. He describes how his organization works with Ascension's acute care and says these partnerships are invaluable. "As long as we keep open the collaboration and communication with those organizations and governing bodies that are supporting us now," he says, "I think we're going to weather the storm just fine."19

A number of constructive proposals have already been made and need to be explored, as to what "solving the nursing home crisis" ought to look like in the aftermath of COVID-19.20 First steps necessarily involve reconfiguring the ways in which Medicare and Medicaid programs invest in elder care across various settings. Some states attempted to allow Medicaid-funded care to be provided at home, for example, but funding has declined overall while a piecemeal approach to coverage has persisted, stymying opportunities for providing comprehensive coverage.

THE ROLE OF SPONSORS

The role of Catholic health care in long-term care is a sponsor question. Sponsors do not set policy or strategy, but they do hold the mission in trust. It is their role to see that it is realized, and maybe even changed.

In CHA's sponsorship formation video, "Go and Do Likewise," Bishop Timothy Doherty refers to sponsors as "sentinels" who must assess their environment and community needs, and determine how the ministry of health care should respond.21

This is part of the prophetic role of the sponsor: to see what others do not see, to discern the spirit in the real situation in which we find ourselves. Sponsorship implies a prophetic function—a capacity to exercise a forward-looking vision for where the health care ministry is being called.

THE MAN FROM MACEDONIA

The book of the Acts of the Apostles describes how the early Christians took up their leader's mission, spreading the good news that God's rule and reign had come in the person of Jesus. All throughout the book of Acts, the narrative shows us how very human God's missional work can be in the concrete: Plans are made; plans are thwarted. Something is tried; it doesn't work. New calls to ministry are made and accepted.

In Acts 16:6-10, a strange event takes place as the apostle Paul is sleeping. He and his team were frustrated because they had been stalled from making any headway into a certain region of Asia Minor. Paul has a vision, in which "a man from Macedonia" stands before him and says: "Come over to Macedonia," the man begs, "and help us." Paul responds to this call and goes to Macedonia where he preaches the Gospel.

IS COVID-19 OUR MACEDONIA MOMENT?

The ministry of health care is a Gospel ministry, a tangible way of preaching the Gospel. Is COVID-19 a call to us to re-assess and re-imagine the future of Catholic involvement in elder care? Can sponsors initiate a conversation about how we should respond and take action?

If a fresh sense of urgency is leading more of us in this direction, we should know by now that we can't do it alone. This is a social issue, and so we will need to widen our conversation to include policy makers, politicians and voters so that our elders have everything they need to age gracefully. Closer to home, we will need to find new ways to collaborate with other ministries—Catholic Charities, education and local parishes—to help ensure that our elders lead not only longer lives, but better lives sustained by community and in a spirit of solidarity, leading ultimately to what we used to call a "happy death," a death relatively free from anxiety and suffering, in the company of family and friends, and above all, enjoying the consolation of faith. All of us should have reason to hope for such an end, and so we all have a share in this mission of care and concern.

FR. CHARLES E. BOUCHARD, OP, is senior director, theology and sponsorship, the Catholic Health Association, St. Louis. ALEC ARNOLD is a doctoral candidate in health care ethics and theology at Saint Louis University and was recently the graduate intern in ethics at the Catholic Health Association, St. Louis.

NOTES

- Michael L. Barnett and David C. Grabowski, "Nursing Homes Are Ground Zero for COVID-19 Pandemic," JAMA, March 24, 2020, https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2763666.

- Valerie Arko, "Transform Podcast #23: Dr. Bill Thomas, Founder of Minka," Senior Housing News, April 8, 2020, https://seniorhousingnews.com/2020/04/08/transform-podcast-23-dr-bill-thomas-founder-of-minka/.

- Figures cited here are drawn from private correspondence between the authors and Susan McDonough, a Catholic eldercare and post-acute specialist, and Lisa McCracken, director of senior living research and development with Ziegler investment banking, through year-end 2019. While the numbers aren't as current, those seeking more information can see "Hot Topics in Catholic Senior Care," a presentation for the Catholic Leaders' Symposium 2019, October 26, 2019, and Susan McDonough, "The 2019 State of Catholic Aging Services," presentation for Catholic Health Assembly 2019, June 9, 2019, https://www.chausa.org/docs/default-source/2019-assembly/2019-Assembly/state-of-catholic-aging-service.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- R.W. Dellinger, "Little Sisters of the Poor Ponder the Future of Home for the Elderly," Angelus News, March 18, 2020, https://angelusnews.com/local/la-catholics/79811-copy/; and Bridget Balch, "Little Sisters of the Poor to Leave Richmond Region–They'd Been Here Since 1874," Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 31, 2019, https://richmond.com/news/local/little-sisters-of-the-poor-to-leave-richmond-region —-theyd-been-here-since/article_a09faffe-be79-512b-bc74-4a8d9c74f4a3.html.

- Rachel M. Werner, Allison K. Hoffman and Norma B. Coe, "Long-Term Care Policy after Covid-19–Solving the Nursing Home Crisis," New England Journal of Medicine, May 27, 2020, https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp2014811?articleTools=true.

- A 1986 study traces the evolution of for-profit elder care and notes that, during the late 1960s, the "Fevered Fifty," corporations owning or planning to own nursing homes, emerged as the "hottest" stocks on the market. In a 1969 article in Barron's, J. Richard Elliott, Jr., explained the phenomenon: "

Of late . . . [a] kind of frenzy seems to grip the stock market at the merest mention of those magic words: 'convalescent care,' 'extended care,' 'continued care.' All euphemisms for the services provided by nursing homes, they stand for the hottest investment around today. Companies never before near a hospital zone — from builders like ITI's Sheraton Corporation, National Environment, and Ramada Inns, to Sayre and Fisher... have been hanging on the industry's door. 'Nobody,' a new-issue underwriter said the other day, 'can lose money in this business. There's just no way.'"

Cited by Catherine Hawes and Charles D. Phillips, "The Changing Structure of the Nursing Home Industry and the Impact of Ownership on Quality, Cost, and Access," in B. H. Gray, ed., For-Profit Enterprise in Health Care (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 1986), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK217907/. - Matthew Goldstein, Jessica Silver-Greenberg and Robert Gebeloff, "Profit Push Takes a Toll in Eldercare," The New York Times, May 8, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/business/coronavirus-nursing-homes.html.

- Howard Gleckman, "Why Are So Many Nursing Homes Shutting Down?" Forbes, March 2, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2020/03/02/why-are-so-many-nursing-homes-shutting-down/#eaf8e6a1712b.

- Charlene Harrington et al., "Nurse Staffing and Deficiencies in the Largest For-Profit Nursing Home Chains and Chains Owned by Private Equity Companies," Health Services Research 47 (2012): 106-28.

- Atul Gupta et al., "Does Private Equity Investment in Healthcare Benefit Patients? Evidence from Nursing Homes," (unpublished paper in progress), SSRN, February, 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3537612. A helpful summary of this article can be found here: https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/benefit-of-private-equity-in-healthcare-lessons-from-nursing-homes.

- See Michael L. Barnett and David C. Grabowski, "Covid-19 Is Ravaging Nursing Homes. We're Getting What We Paid For," The Washington Post, April 16, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/16/covid-19-is-ravaging-nursing-homes-were-getting-what-we-paid/. See also Maria Castellucci, "Nursing Homes Brace for New Medicare Payment System," Modern Healthcare, May 25, 2019, https://www.modernhealthcare.com/post-acute-care/nursing-homes-brace-new-medicare-payment-system.

- Matthew Goldstein, Jessica Silver-Greenberg and Robert Gebeloff, "Push for Profits Left Nursing Homes Struggling to Provide Care," The New York Times, May 7, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/business/nursing-homes-profits-private-coronavirus.html.

- Maggie Flynn, "Multi-State Nursing Home Operators Navigate Conflicting COVID-19 Rules," Skilled Nursing News, April 22, 2020, https://skillednursingnews.com/2020/04/multi-state-nursing-home-operators-navigate-conflicting-covid-19-rules/.

- Concerning the overall need to shift out of a hospital-based paradigm, a commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine by Italian physicians surmised that hospitalized COVID-19 victims there might be facilitating transmission to uninfected patients, and that home care and mobile clinics could help patients with mild symptoms. They drew the following lesson: "Western health care systems have been built around the concept of patient-centered care, but an epidemic requires a change of perspective toward a concept of community-centered care;" Mirco Nacoti et al., "At the Epicenter of the Covid-19 Pandemic and Humanitarian Crises in Italy," NEJM, March 21, 2020, https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0080.

- CHA, "Creating Age-Friendly Health Systems," https://www.chausa.org/eldercare/creating-age-friendly-health-systems.

- Arko, "Transform Podcast #23."

- Arko, "Transform Podcast #23."

- Joyce Famakinwa, "Senior Care Innovator Bill Thomas: COVID-19 Rewriting Health Care Rules, Pushing Home Care into the Spotlight," Home Health Care News, April 20, 2020, https://homehealthcarenews.com/2020/04/senior-care-innovator-bill-thomas-covid-19-rewriting-health-care-rules-pushing-home-care-into-the-spotlight/.

- Tim Regan, "Ascension Living President: Pandemic Proves Value of Health System, Senior Living Integration," Senior Housing News, October 19, 2020, https://seniorhousingnews.com/2020/10/19/ascension-living-president-pandemic-proves-value-of-health-system-senior-living-integration/. The podcast upon which this print piece was based is available at https://seniorhousingnews.com/2020/10/22/transform-podcast-34-danny-stricker-of-ascension-living/.

- Werner, Hoffman and Coe, "Long-Term Care Policy after Covid-19."

- CHA, "Sponsorship Part 7 Formation," at 4:45, part seven of the series, "Go and Do Likewise," YouTube video, uploaded March 4, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgTP7Y2viUk.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSIONFr. Charles Bouchard, OP, and Alec Arnold, PhD (c), are concerned with the role of Catholic health care in long-term care facilities. They explore the mission commitments and financial viability of traditional forms of eldercare and raise important questions about where the ministry should go from here in the care of vulnerable people who are old. - What do you think about the mission vs. margin equation that Catholic ministries have to deal with in evaluating long-term care services and facilities? As difficult decisions have to be made about doing the most good with limited resources who needs to be at the table when discernment takes place?

- In explaining the importance of real estate to the viability of long-term care, Bouchard and Arnold make a surprising comparison to the McDonald's business model. What do you think of the validity of that comparison? Talk about the value of the ministry's holdings vs. the commitment to mission.

- The article leads to the challenging question of what role sponsors may have in shaping the future of long-term care in the Catholic health ministry. Does your ministry use your sponsors as prophets with a forward-looking vision for where the health care ministry is being called? Do you think they have the right relationship with executive leadership? How would you change it if you could?

|