DAVID LEWELLEN

Contributor to Health Progress

Illustration by Roy Scott

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit more than a year ago, Keri Rodrigues' kids, like millions of others, did their best to learn through a computer screen. And until this February, that was the best arrangement for them. But as time went on, she could see that her third-grade son was suffering in virtual public school. Every added "day of Zoom in isolation, staring at the same wall," was worsening his mental health, until "my fear of the virus became less than my fear of isolation," she said. "My son was dreading his life, at 9 years old."

Rodrigues, a Boston-area mom who is president of the National Parents' Union, called the local Catholic school where her children had attended two years earlier and arranged for two of her children to start in-person schooling the following week.

The two boys were moving toward a much better end to their school year. After her second grader's first day back, even amidst the masks and plexiglass, he reported when he came home, "I made 10 friends today." Nothing about going to school in 2021 is normal, but the new arrangement felt closer to it. "He felt that the teacher saw him, and he wasn't a box on the screen," Rodrigues said.

More than 50 million children are enrolled in K-12 schools in the United States, and over the past year-plus, every one of them has a story to tell about disrupted education. The stories vary wildly. Some children thrived on learning at home, without bullies, distractions or sensory overload. Some children, cut off from friends, food and security, spiraled downward.

As a general rule, however, America's pre-existing racial and income disparities have gotten worse. Affluent white children made gains or held their ground; low-income children of color fell further behind. It's a sad story, but many observers hope that this is a moment when big changes can be made that will benefit the overlooked, especially when "back to normal" is not acceptable.

"A lot of parents don't want to engage with the school system on a good day, let alone in a pandemic," said Rodrigues, whose organization advocates to improve children's quality of life and educational experience. Parents who were more comfortable sending their children back early "are used to having their needs met, because they don't fear the system." Rodrigues herself bounced between foster homes as a teen and was expelled from school, so she knows that it does not represent a welcoming place for every child. Bullying happens; racism is real.

For some children, "school's not a healthy environment for them. They feel safer at home," said Kenneth Shelton, an education consultant and speaker in southern California. He told the story a parent relayed to him, saying he's hearing more instances like it: A Black child saw a classmate wearing an offensive T-shirt on Zoom — hiding the classmate's image was an easier temporary fix than leaving school or complaining to a principal.

Teaching via Zoom presents other opportunities for thinking creatively. Rather than argue with students over turning cameras on or off, Shelton said, "If I were teaching now, I'd encourage students to change their backgrounds as a component of what they're learning."

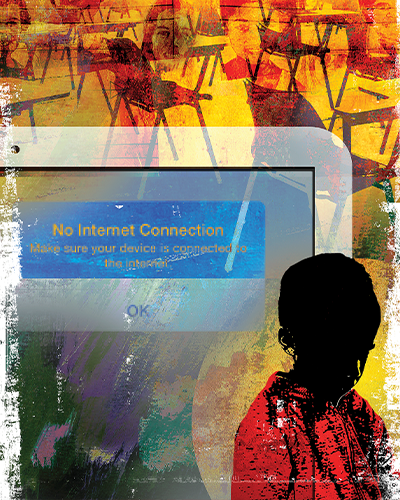

PANDEMIC HIGHLIGHTS EDUCATIONAL DISPARITIES

When Rocketship Public Schools closed in person, "our kids still needed academic support, but we heard about a lot of new needs," said Juan Mateos, Bay Area director for the system, which operates 20 charter elementary schools in four major markets. Most of their students were low-income, and housing, child care and food suddenly became more urgent situations for many families. The system scrambled to find electronic devices for students, but Internet access could not be taken for granted, either. Mateos said that Rocketship paid for some families' Wi-Fi access, and employees had to show grandparents and day-care providers how to log on and join a Zoom session so that the children in their care could attend virtual school.

As time went on, the system began offering in-person school, depending on parent feedback and also on local guidelines; there were times when the three California counties where Rocketship has schools each had different rules.

For many of Rocketship's students, "their parents are working the local grocery store, or they're medical assistants, and they are being recognized for the essential role they do play in society," Mateos said. But recognition of those essential jobs, for the most part, has not translated into better salaries and benefits.

During the mad scramble to shift online, Shelton said, districts were making "stopgap decisions based on the information they had. But once you have more information, an entire year's worth, what are you choosing going forward? What happened before wasn't working, and it was a Band-Aid." It's a much bigger issue than just the school system: "We need to hold a mirror to ourselves and society and ask what kind of America we want." Fair and universal access to high-speed Internet would be a start, he said — and treating big tech companies as public utilities would increase access to education and to many other opportunities.

Shelton also thinks it's significant that across the nation, standardized tests were canceled last spring, even as schools did their best to keep teaching children. If education continues without the standardized tests, "how valuable are they in the first place?" he asked.

Power struggles erupted, too — between teachers and administrators, between parents and districts, and between those who insisted that schools must reopen right now (or yesterday) and those who insisted on keeping everyone home until the last arm is vaccinated. Almost every possible variation of hybrid education was tried somewhere or other — split weeks, split days, split classes.

In delivering education during a pandemic, "everyone is really frustrated," said Curtis Jones, a senior scientist in the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, "but some people are frustrated about different things than other people." One family he interviewed was upset about paying $2,000 a month for a private tutor to keep their child from falling behind; another family was parking next to a McDonald's so their child could have Wi-Fi access.

In the fall of 2020, Jones said that with more time to plan, most districts offered much more robust online programming and satisfied more needs, if not all of them. "The average student got a better experience" than in the spring of that year, he said. "But the negative effects were not randomly distributed across the United States." Just as COVID-19 has hit low-income adults and some communities harder, so have the social and economic impacts. "Every measure you look at, you could say that white middle-class people are doing better than before," Jones said. "The same could be said for education." The achievement gap between white students and everyone else seems to be getting even wider, but it draws attention only when white students fall a few months behind the standard, not when children of color are two years behind.

Districts serving more affluent students were more likely to reopen sooner for in-person learning. Large urban districts, Jones said, tend to have stronger teachers' unions, "and they are understandably cautious about going back." In affluent districts, he said, parents have more power and influence because of the leverage of possibly withdrawing their children and putting them in another district, with a corresponding loss of state funding.

Many people say they want to go back to normal, "but Black or brown or Native American students don't. We need a new normal. We need to re-define what normal is and work toward it. Can we open schools in a way that promotes success more equitably?" Jones asked. On average, "white students are doing really well. We need to help students who rely on school for more things." 1

One of those things, the nation has been forced to realize, is child care. Teachers will reflexively say that it's not their job to babysit kids, but Rodrigues pointed out that if parents leave their children with someone else, essentially schools do function as a child care system, among their other duties. The American economy and workforce has come to depend on it, "and it's the great tradeoff."

Social and emotional learning, a growing buzzword in the last decade or two, was also pushed to the front burner — parents who might not have been aware of it suddenly realized that it was something their children were missing at home. "We've seen a lot of creative and different ways that teachers are trying to teach it," said Justina Schlund, senior director of content and field learning for the Center for Social and Emotional Learning. For instance, the elementary school custom of "morning meeting," where students check in with the teacher and each other, easily moved to an online setting, and kids could talk about how it felt to be in quarantine. "The energy of students is driving the academic part of the day, because students feel more engaged," she said.

CAN EDUCATIONAL ADAPTATIONS IMPROVE HEALTH?

A first change to adapt to the new circumstances we find ourselves in, Rodrigues said, would be a summer catch-up session. The custom of starting a new grade in the fall after three months off is "an arbitrary date set by administrators. The needs of children have nothing to do with it."

Another opportunity to make changes for the better, Shelton said, is with school start times. Data clearly show, he said, that starting at 8:15 or 8:30, instead of the pre-8 a.m. times that are relatively common, reduces traffic accidents, depression, obesity and drug use, and also results in "kids who aren't tired and beaten down at the beginning of the school day."

"Everything that we've been told is impossible is now possible," Rodrigues pointed out. "We're learning a lot about how kids learn better and how we can do better. There are a lot of things to love about this moment. Let's make sure we don't slide back to the familiar status quo that didn't work."

Cynthia Henderson, a senior practitioner for school social work at the National Association of Social Workers, said, "The kids we sent home when we closed schools are not the same kids that came back." Quarantined at home, grieving the loss of loved ones or stable routines, relying for help on parents who themselves might not understand the academic material or the technology, "imagine the level of frustration." In lower-income neighborhoods, sometimes several children had to share one device — assuming a parent didn't need it. And in rural areas, getting access to the internet cannot be taken for granted. "Money is the final connection," Henderson said.

Surveys of school social workers found that a large number had lost contact with "their" kids, and were worried about their food and housing situations, and about increased domestic violence. Henderson said she also knew of cases where students were home alone because their parents had to work, and other cases of older children who dropped out of online school to find jobs to help support their families.

WORKING TOWARD EQUITY

"Our Black, brown and indigenous communities have been hit hard by three pandemics," said Kim Anderson, executive director of the National Education Association — COVID-19, economic disruption and racial reckoning. "Those are all areas of significant trauma to students and educators. This triple crisis has laid bare inequities that have existed for hundreds of years. We have a public education system that was designed inequitably," first and foremost by relying on property taxes for funding. "That's the real conversation. Not about who's to blame, but about how to unravel that system and build an equitable system."

Low-income and minority families have long distrusted the school system, "and for good reason," said Tomeka Davis, an associate professor of sociology at Georgia State University. "They see the pandemic, and they're the ones who are affected the most." The past year-plus has "turned the light on to things we weren't paying attention to. We've been talking about inequality in schools for years. Now we have this accident of history, and we see all the problems of inequality. It should make us change the way we do things, but I don't think anything's going to change. I really hope I'm wrong."

Anderson asked, "How can we take this moment and use it as a catalyst to build the system we need?" This is an exciting moment. There's going to be trauma, but once we recover, why not seize the moment to come together? That's a goal that we've never lived up to as a country."

DAVID LEWELLEN is a freelance writer in Glendale, Wisconsin, and editor of Vision, the newsletter of the National Association of Catholic Chaplains.

NOTE

- Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE), "COVID-19 and the Educational Equity Crisis," Jan. 25, 2021, https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/covid-19-and-educational-equity-crisis.