BY KATHY OKLAND, RN, MPH, EDAC AND ADELEH NEJATI, AIA, PhD, EDAC

Illustration by Cap Pannell

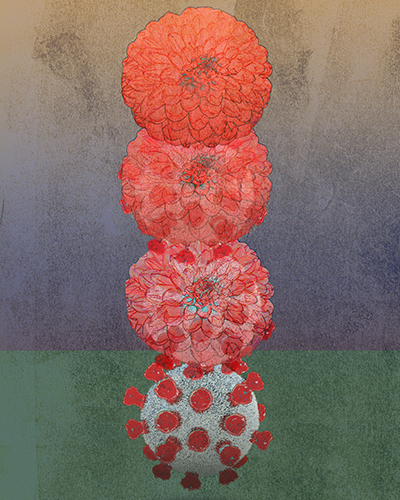

COVID-19 has laid bare the finite capacities of resources to care for our communities and our country, not the least of which is the very capacity to care. Providing care is physically and emotionally demanding, which is why it's essential that health care systems provide staff with places to recharge and find renewed peace for the soul. These spaces are essential for health and the health care workforce.

The pandemic not only exposed but exacerbated many of the vulnerabilities of the health care system and those who deliver its services. Often, nothing has been done about it. As we confront the greatest health care challenge of our time, there's a compelling conversation to be had about how health care systems can create spaces that allow staff to have separation and solitude from stressors. Health care workers have stories of retreating to a corner in the cafeteria, their car or a bathroom stall to gather themselves before resuming the remainder of their shift. This experience is shared by physicians, technicians, therapists and nurses alike.

While any health care worker can experience stressors, the pandemic also has raised the visibility of nurses and their capacity to care for patients in a climate of sustained surge, unprecedented supply shortfalls and immense emotional toll. Nurses make up the largest part of the health care workforce in the U.S. and globally, and it has been recognized that nurses play a vital role in improving health outcomes around the world. What has not been widely addressed is how the design of the work environment can contribute to nurse well-being. It is important to note that pre-pandemic, nurses were already stressed, under-resourced and exhibiting signs of fatigue and distress.

THE DILEMMA

According to nurse leaders, the emotional health and well-being of staff are among the top three challenges of the pandemic.1 Sixty-six percent of nurses worry that their job is affecting their health.2 By some estimates, clinicians account for nearly 20% of the COVID-19-infected cases in the United States.3 In July 2019, the World Health Organization formally designated burnout as an occupational phenomenon, not a medical condition. While awareness of this situation has increased, there has been little done to provide designated areas for retreat and relief for those affected.

There is reason to celebrate the attention given to mindfulness, meditation and massage chairs, yet little consideration is being given to the physical settings for respite and how they are appointed in support of emotional and physical comfort and recovery. The root cause, contributing factors and means to address fatigue and burnout are complex. No single process or design intervention will produce significant, sustained results. Without areas designed and devoted to decompression and rest, individuals caring for others will not have the opportunity to be at their best. It is for that reason we wanted to examine the past and present dilemma, what current research reveals and actionable insights that support places for restoration in health care environments today.

THE DATA

Health care facilities are one the most stressful work environments for their employees, and this is especially true for nurses. Hence, one of the concerns of current health care research is how the needs of nursing staff can be better incorporated into the design of health care environments. Identified as the first controlled study at Legacy Emanuel Medical Center in Portland, Oregon, researchers investigated the influence of taking work breaks in a garden on nurse burnout. The impact of nurses taking daily work breaks in a hospital garden was shown to reduce burnout and feelings of anger and tiredness. The garden outperformed quality interior break rooms, and the study supported taking a break in a hospital-integrated garden as part of a multi-modal approach to reduce burnout for nurses.4

A 2015 study of more than 1,000 medical surgical nurses in the United States showed that the majority (68.1%) of nurses suffer from a stress level of 7 or higher on a scale of 0-10. Taking breaks was mentioned as the main activity nurses did within their work environment to relieve stress. The results indicated that staff break areas are more likely to be used if they are in close proximity to nurses' work areas, offer complete privacy from patients and families, and provide a mixture of opportunities for individual privacy and socialization with co-workers. Having physical access to private outdoor spaces (for example, balconies or porches) was shown to have a significantly greater restorative effect in comparison with window views, artwork or indoor plants.5

In 2020, the coauthors of this article, supported by Chief Nurse Executive, National Patient Care Services, Linda Knodel with Kaiser Permanente, replicated that study of designing staff restorative environments in health care facilities with nurse leaders from the of American Organization for Nursing Leadership (AONL) and the Nursing Institute for Healthcare Design (NIHD).6 Replicating the study provided the opportunity to compare and contrast perspectives of practicing bedside nurses and nurse leaders who manage and provide oversight to care. Results indicated that the majority (63.6%) of nurse leaders also suffer from a stress level of 7 or higher. Taking a walk was the main activity nurse leaders mentioned as a way to relieve stress in their work environments. The main feature of an ideal break room was stated as being "quiet." The nurse leaders requested a high level of privacy (from patients and families) for outdoor break areas in order to have a restorative effect. When asked to identify a single element to improve break room utilization, nurse leaders responded that nurses needed enough time to take breaks. Asked to identify the single greatest barrier preventing break room utilization, their response was the same: not having enough time to take breaks.

Convenience is key to nurses for any spaces they use at work. Whether they visit a conventional break room with lockers, a lunchroom and rest room — or an idealized respite room designed for privacy, views of nature and close to their patient assignment — both require considerations for COVID-19. To protect health care workers from infectious disease transmission, planning for their entry and exit is important. Masks, goggles, gowns and respirators are standard, with some variation based on an organization's specific infection prevention policy. Practical consideration must be given to accessible and individualized storage for personal protective equipment (PPE), both single-use (requiring disposal) and re-use that may require cleaning, disinfecting, drying and hanging. For battery-powered protection devices, power receptacles for recharging and/or battery packs need to be considered. For respirators, canister and filter availability is essential. This suggests that whether retrofitting existing space or designing for new construction, even support spaces for rest and retreat require careful consideration and planning. Astute planners will seek out evidence-based research that supports the complexities inherent in health care planning and design.

The majority of the nurse leaders reported that high-quality break spaces were "fairly" or "very" important for increasing nurses' job satisfaction (85.6%), increasing nurses' job performance (83.5%), and alleviating their work-related health concerns (72.9%). We asked nurse leaders, now with the COVID-19 experience, if the need for break and respite accommodations is more important to them. The great majority of them (80%) reported that the need for a staff restorative environment is even more important than ever before.

Further analyses showed that the perceived level of stress in the work environment was a significant predictor of the importance that nurse leaders assigned to break areas. In addition, when nurse leaders took more restorative breaks themselves, they were more likely to emphasize the importance of high-quality break areas. Nurse leaders who viewed their current break spaces as unsatisfactory strongly believed that improving these areas would be of benefit to nurses' health and well-being, especially given their experience from the pandemic. It is the belief of the researchers (and authors), that raising awareness about spaces for rest for nurses will do the same for other care team disciplines involved in the patient and family experience. Other than the "on call sleep room" or the chapel (if the facility has one), few spaces exist to support quiet and private environments for retreat and renewal.

For the first time, a building standard acknowledges supportive policies and environmental features for staff restoration as part of their rating system. The WELL Building Standard is an evidence-based system for measuring, certifying and monitoring the performance of building features that impact health and well-being. This standard includes restorative opportunities, programs and spaces as part of their "Mind" concept, which aims to promote mental health through policy, program and design strategies to address the diverse factors that influence cognitive and emotional well-being.7

The concept focuses on the connection between the human mind and body, and how to optimize health through design technology and treatment strategies. After reviewing recent empirical evidence and its incorporation in leading industry guidelines and standards, it is time to put research-informed ideas into action and integrate innovations into the design of staff restorative environments.

DEMONSTRATING THE DATA

Preventing nurse burnout and recovering from workplace stress requires supportive policies and programs to ensure that nurses have appropriate breaks, as well as health-promoting respite areas to make sure those breaks are restorative and refreshing. The critical factor is having an integrated platform of policies, programs and environmental design interventions. Without doubt, health care providers have been experiencing incredible burdens due to COVID-19. However, there are stories from the pandemic of places that have created spaces to reduce stress and burnout among health care professionals.

To promote the well-being of health care staff, Kaiser Permanente proposed relaxation areas in their medical centers. Executives were asked to identify available spaces including family/visitor waiting areas that were not being used during the pandemic. They were also asked to furnish these areas with dimmed lighting, calming music, aromatherapy, healthy snacks and massage chairs.8

When COVID-19 hit New York City, David Putrino, director of the Rehabilitation Innovation Lab at the Mount Sinai Health System, converted his lab into recharge rooms for front-line health care workers. His focus is how technology can help human health and well-being. In these recharge rooms, he started by adding artificial plants that create a cocoon-like natural surrounding for a person. Beautiful images of natural scenes were projected on the walls with added music and aromatherapy. A survey revealed that 15 minutes in a recharge space across 146 visits resulted in, on average, 65% reduction in stress.9

At Dignity Health Marian Regional Medical Center in Santa Maria, California, clinical educator Sarah Phillips created two relaxation rooms for fellow staff to have spaces of respite and quiet during these stressful times. The spaces are filled with items from Sarah's home and community donations. Located directly across from critical care, they are quiet with low light and include greenery, aromatherapy, relaxing white noise, massage chairs and inspirational reading materials. The rooms have had significant use by staff since being created. 10

Armed with the awareness that human behaviors are influenced by the physical environment, that rest equals restoration, and that research supports both, what are the next steps to create the climate and conditions for rest?

- First, observation and evaluation. Tour the areas deemed for break and respite in their current state. Ask staff where they go to decompress and/or make sense of difficult days. Pause and consider the characteristics of those environments. Do they align with the research findings that call for quiet, private areas with natural light? If so, listen and challenge any assumption that locations for renewal require significant renovation, reconstruction or even its own room. Rethink real estate, then innovate.

- Second, a perfect place for health care workers to rest without policies, programs and a philosophy behind it is doomed to fail. Leadership advocacy and support is as essential as the need is to destress itself.

- Finally, who is supporting the needs of caregivers? If spaces for rest were conceived of as an intervention for them, would they be supported and designed differently? Further, this work is more than solving a problem. What if instead, it is viewed as serving people's souls? Would design decisions for these spaces be philosophically and financially supported?

For health care professionals to be at their best, there must be available resources for their rest and recovery — that which supports caregivers supports patient outcomes. Creating healing environments and places for respite are critical preconditions to providing healing for patients and families and for those who care for them.

KATHY OKLAND is a nurse and health care consultant interested in the influence of the environment on patient and caregiver experience. She lives on Spirit Lake, Minnesota. ADELEH NEJATI is an associate principal, health care planner and researcher with HMC Architects in San Francisco.

NOTES

- American Organization of Nursing Leadership and Joslin Marketing, "Nursing Leadership COVID-19 Survey Key Findings," August 4, 2020.

- AMN Healthcare, "2019 Survey of Registered Nurses: A Challenging Decade Ahead," November 12, 2019.

- Tinglong Dai, Ge Bai and Gerard F. Anderson, "PPE Supply Chain Needs Data Transparency and Stress Testing," Journal of General Internal Medicine 35, no. 9 (2020): 2748-49.

- American Hospital Association, "Hospitals and Health Systems Continue to Face Unprecedented Financial Challenges Due to COVID-19," June 2020.

- Makayla Cordoza et al., "Impact of Nurses Taking Daily Work Breaks in a Hospital Garden on Burnout," American Journal of Critical Care 7, no. 6 (2018): 508-12.

- Adeleh Nejati et al., "Restorative Design Features for Hospital Staff Break Areas: A Multi-Method Study," HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 9, no. 2 (2016): 16-35.

- International WELL Building Institute, "WELL Building Standard v2," last modified 2020, https://v2.wellcertified.com/wellv2/en/overview.

- Kaiser Permanente, Care for the Caregivers' Relaxation Rooms, 2020 Draft Proposal.

- Minyvonne Burke, "Coronavirus Stress Among Hospital Workers Leads to Creation of 'Recharge Rooms'" NBC News, July 22, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/coronavirus-stress-among-hospital-workers-leads-creation-recharge-rooms-n1234607.

- Dignity Health, "Dignity Health Central Coast Nurse Creates 'Relaxation Rooms' to Offer Respite to Health Care Staff," April 9, 2020, https://www.dignityhealth.org/central-coast/locations/frenchhospital/about-us/press-center/2020-04-09-relaxation-rooms.