BY: ANDREA BRASSARD, RN, D.Nsc., M.P.H., F.N.P.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is expected to provide health insurance to up to 32 million previously uninsured Americans, primarily through expanded Medicaid coverage. Their numbers will swell a health care system already ill-equipped to cope with the demographic bulge labeled "baby boomers," that is, the approximately 76 million people born in the U.S. between 1946 and 1964 and now reaching retirement age.1

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Institute of Medicine launched a study of the nursing workforce's ability to meet the challenges of Medicaid expansion at the same time the U.S. health care system is being redesigned. Health care's new emphasis: primary care, that is, integrated, accessible health care services provided by clinicians who are accountable for preventing illness, treating disease in early stages and avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations and emergency-room visits.

The 2011 Institute of Medicine consensus report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health2 is a blueprint for how nurses can fill new and expanded roles in a health care system that focuses on primary, patient-centered care and wellness over the acute-care model. Notably, as more and more patients become Medicaid-eligible, registered nurses (RNs) and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) can deliver cost-effective care in inpatient and outpatient settings, the report says.

However, state and federal laws and other barriers have limited the ability of nurses to practice to the full extent of their education, training and competence. The Center to Champion Nursing in America is an initiative of AARP, the AARP Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to increase the nation's capacity to educate and retain nurses. Its national Campaign for Action is working to eliminate outdated laws and practices that get in the way of nursing's role in the new model of health care.

In primary care settings, RNs can provide preventive measures such as screening and immunizations and can help manage chronic conditions by educating and counseling patients and their family caregivers in the provider's office or by telephone or telehealth.3

In hospital settings, RNs have implemented innovative quality programs such as Transforming Care at the Bedside. Under the program, teams generate innovative ideas to improve the safety and reliability of care, increase the patient-centeredness of care, focus on building effective care teams and develop systems that enhance the timeliness, reliability and efficiency of delivering quality care. These teams are a cost-effective way to improve patient outcomes such as decreased falls and other complications.4

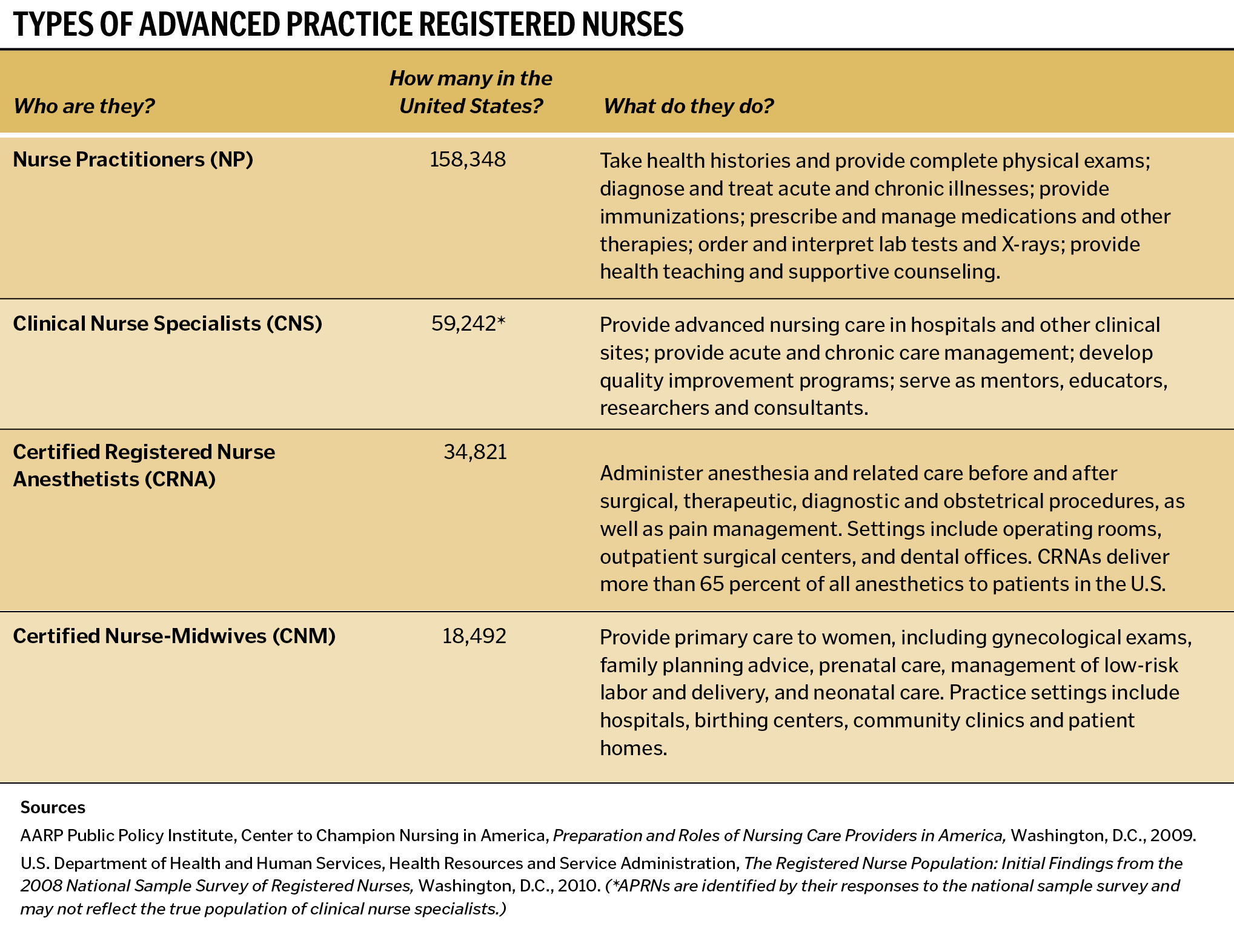

Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) are RNs with additional education and training. APRNs provide high quality primary care, preventive care, transitional care, chronic care management and other services particularly necessary for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Nurse practitioners and certified nurse-midwives are two types of APRNs that provide primary care. They take health histories, provide complete physical exams, diagnoses and treat many common acute and chronic problems, interpret lab results and other diagnostic tests, prescribe medications and teach and counsel patients and their families about health and illness. Certified nurse-midwives care for women before, during and after childbirth and also provide primary care services to women from adolescence to late life. Women receiving care from certified nurse midwives have shorter labors, fewer Caesarean births, less perineal trauma, higher breastfeeding rates and lower infant and maternal mortality rates.5

For example, the Family Health and Birth Center (www.yourfhbc.org) is a Medicaid provider in northeast Washington, D.C. staffed by certified nurse-midwives and serving primarily African American women. The center estimates that its lower rates of Caesarean sections, premature deliveries and low-birth-weight infants add up to more than $1 million dollars in annual savings.6

Patients receiving primary care from nurse practitioners report high satisfaction with their provider of choice. Research shows no difference in outcomes of primary care delivered by a nurse practitioner or a physician, including health status, number of prescriptions written, return visits requested or referrals to other providers.7 Additionally, outcomes of care for chronically ill patients, such as blood pressure control, lipid control and glucose control, were equivalent whether the provider was a nurse practitioner or a physician.8 Care from a nurse practitioner is also equivalent to physician care in terms of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, duration of ventilation and mortality.9

Nurse practitioners are an important provider for Medicaid beneficiaries. According to the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 87 percent of nurse practitioners see patients covered by Medicaid.10 About 20 percent of nurse practitioners practice in rural settings,11 double the estimated number of rural physicians.12

Bambi McQuade-Jones, family nurse practitioner, is the executive director of Boone County Community Clinic in Lebanon, Ind. McQuade-Jones and Georgia Steiman, women's health nurse practitioner, provide primary care to patients with Medicaid, Healthy Indiana Plan (a state plan offering coverage to uninsured adults ages 19-64) or no insurance (sliding fee scale). Services include preventive care, acute care and sick visits and chronic disease care as well as lab tests, referrals and care coordination. The clinic provides prenatal care to women referred from the local pregnancy crisis center. Although these women are usually Medicaid eligible, it takes up to six months for their Medicaid coverage to begin. The clinic also has created an innovative health and wellness program called "H.E.R.S. for Her," offering health education resources and services for uninsured and economically vulnerable Boone County women ages 14 to 44. The program includes a free YMCA membership and referrals to a range of community-based services.13

In rural Iowa, Cheryll Jones, pediatric nurse practitioner, runs a child health specialty clinic. Funded by Title V block grants and Medicaid, the clinic serves children with special needs including autism, behavioral problems and chronic illness. The clinic providers include a nurse practitioner, a registered nurse, a family navigator (who is the parent of a special needs child) and an administrative assistant. The clinic has low rates of rehospitalizations and emergency department visits, which Jones attributes to their emphasis on case management, collaboration with medical home providers and advocacy.

Jones says, "Nurse practitioners excel at care coordination because we were trained as nurses first. We have a holistic approach to health care, partnering with public health providers and advocating for community resources."14 The clinic engages with scarce specialist providers through telehealth. Telehealth providers include a child psychiatrist, dietitian and, most recently, a behavioral health specialist.

Expansion of these kinds of nurse-practitioner-led clinics is limited by restrictions in some to physician-nurse practitioner collaboration. Also, in states where physician oversight is required for nurse practitioners to practice, additional fees are engendered for medical direction, even for services within the APRN's scope of practice.

Advanced practice registered nurses deliver health care services in more than half of U.S. community hospitals,15 and 43 percent of nurse practitioners hold hospital privileges.16 The three other APRN categories — certified nurse-midwives, certified registered nurse anesthetists and17clinical nurse specialists — typically practice in hospitals and other acute-care settings.18 Most certified nurse-midwives attend live births in hospitals or in hospital-based birthing centers.19

Certified registered nurse anesthetists provide anesthesia and pain management services, particularly in rural and underserved communities. Research on their services reveals safe, quality patient care with or without physician supervision.20 When they practice independently, CRNAs can provide anesthesia services at 25 percent lower costs, since anesthesiologists are not charging supervision fees.21

Clinical nurse specialists provide expert consultation and care coordination, and they implement quality improvement programs in hospitals and other health care settings. Outcomes of CNS care include reduced hospital costs and length of stay, reduced frequency of emergency department visits, fewer medical complications in hospitalized patients and increased patient satisfaction with nursing care.22

Mental health services are going to require special consideration as more Americans gain Medicaid coverage. In a national survey, 1 in 4 Americans reported a clinically significant mental health problem in the preceding 12 months.23 APRNs can help meet this need. Two categories of APRNs have specialty training in psychiatric mental health and addictions — psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists. These APRNs can provide a full spectrum of integrated health care, including assessment and diagnosis, psychotherapeutic interventions, writing prescriptions and managing medication regimens, as well as providing care coordination. Patient outcomes are at least as good as and often better than other mental health specialists, because psychiatric mental health APRNs focus on the quality of the relationship as central to the healing process while integrating the use of medicine, therapy and complementary treatments.24, 25

THE FUTURE OF NURSING

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing is working to reduce the state-by-state variation in how advance practice registered nurses are regulated in licensure, education and practice for all four APRN categories.26 The group believes that because of their advanced education, training and skills, ARPNs should have statutory autonomy — the ability to prescribe medications, order tests and sign treatment forms — without restrictive physician oversight and its accompanying cost. Statutory autonomy does not mean that APRNs will practice independently; like all health professionals, they will refer and consult with physicians and other providers.

On the federal level, APRNs are not permitted to certify patients for home health and hospice services. By requiring physician sign-off, patient access to needed care can be delayed with resultant possible rehospitalizations or emergency department visits.27 Similarly, in many hospitals, organizational barriers prevent registered nurses from referring patients to home health and hospital services. Hospital policies that require a physician's order for a patient to be referred for post-acute care services add delays and unnecessary bureaucracy.

In addition to being able to make post-acute care referrals, registered nurses should be able to make changes to their patients' care within the realm of nursing care. For instance, RNs should be able to discontinue indwelling catheters and order pressure-reducing equipment based on the patient's condition and standard guidelines, rather than wait for a physician order. Removing such organizational barriers to RN care in inpatient settings can reduce hospital-acquired urinary tract infections and pressure ulcers. RNs should also be able to administer routine vaccines in both inpatient and outpatient settings based on standard guidelines.

The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health should be required reading for hospital executives who are seeking to transform health care through nursing. For a summary of how nurses are solving some of primary care care's most pressing problems, refer to the most recent Robert Wood Johnson Foundation issue brief, Implementing the IOM Future of Nursing — Part III.28

This short article has highlighted models for expanding RN and APRN care to meet the challenges of an expanded Medicaid population. For more information on how to transform health care through nursing, visit www.campaignforaction.org

ANDREA BRASSARD is senior strategic policy adviser, Center to Champion Nursing in America, an initiative of AARP, the AARP Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. She is based in Washington, D.C.

NOTES

- American Association of Medical Colleges, "Why Is There a Shortage of Primary Care Doctors?" https://www.aamc.org/download/70310/data/primarycarefs.pdf.

- Institute of Medicine, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011).

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, "Use Exemplary Nursing Initiatives to Expand Access, Improve Quality, Reduce Costs, and Promote Prevention," Charting Nursing's Future, issue 9 (March 2009): www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=41388.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The Business Case for TCAB: A Cost-Benefit Analysis, www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/21843.pdf.

- Jeanne Raisler, "Midwifery Care Research: What Questions Are Being Asked? What Lessons Have Been Learned?" Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 45, no. 1 (2000): 20-36.

- Institute of Medicine, "Case Study: Nurse Midwives and Birth Centers," in The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2011).

- Sue Horricks, Elizabeth Anderson and Chris Salisbury, "Systematic Review of Whether Nurse Practitioners Working in Primary Care Can Provide Equivalent Care to Doctors," British Medical Journal, 324 (2002): 819-823.

- Robin P. Newhouse et al., "Advanced Practice Nurse Outcomes 1990-2008: A Systematic Review," Nursing Economic$ 29, no. 5 (2011). www.nursingeconomics.net/ce/2013/article3001021.pdf.

- Newhouse.

- American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, AANP Clinical Survey 2009-2012 (Austin, Texas: American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 2011).

- AANP Clinical Survey 2009-2012.

- United Health Group, Modernizing Rural Health Care, Working Paper 6 (July 2011) www.unitedhealthgroup.com/hrm/unh_workingpaper6.pdf.

- Boone County Community Clinic www.boonecountyclinic.org/Site/_H.E.R.S._for_HER_.html, accessed Aug. 17, 2012.

- Cheryll Jones, pediatric nurse practitioner, Ottumwa, Iowa, personal communication, Aug. 14, 2012.

- American Hospital Association, "Dashboard," Trustee Magazine (March 2012): 36.

- AANP Clinical Survey 2009-2011.

- Andrea Brassard and Mary Smolenski, Removing Barriers to Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Care: Hospital Privileges (Washington, D.C.: AARP Public Policy Institute, September 2011).

- Kerri D. Schuiling, Theresa A. Sipe and Judith Fullerton, "Findings from the Analysis of the American College of Nurse-Midwives' Membership Surveys: 2006-2008," Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health 55, no. 4 (July/August 2010): 299-307.

- American Association of Nurse Anesthetists, "Research Topics and Articles," accessed August 20, 2012, www.aana.com/resources2/research/Pages/Research-Topics.aspx.

- Lorraine Jordan, "Studies Support Removing CRNA Supervision Rule to Maximize Anesthesia Workforce and Ensure Patient Access to Care," AANA Journal 79, no. 2 (April 2011): 101-104.

- National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists, www.nacns.org/docs/NACNS-Brochure.pdf.

- Benjamin G. Druss et al., "Understanding Mental Health Treatment in Persons Without Mental Diagnoses: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication," Archives of General Psychiatry 64, 10 (2007):1196-203.

- Nancy P. Hanrahan, Kathleen Delaney and Elizabeth Merwin, "Health Care Reform and the Federal Transformation Initiatives: Capitalizing on the Potential of Advanced Practice Psychiatric Nurses," Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice 11, no. 3 (2010): 235-44.

- Nancy P. Hanrahan et al., "Randomized Clinical Trial of the Effectiveness of Home-Based Advanced Practice Nursing on Outcomes for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness and HIV," Nursing Research and Practice ,vol. 2011.

- Nancy P. Hanrahan and David Hartley, "Employment of Advanced-Practice Psychiatric Nurses to Stem Rural Mental Health Workforce Shortages," Psychiatric Services 59, 1 (2008):109-11.

- www.campaignforaction.org.

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing, "Campaign for APRN Consensus," https://www.ncsbn.org/aprn.htm.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Implementing the IOM Future of Nursing — Part III, July 2012, www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=74721.

WHO ARE ADVANCED PRACTICE REGISTERED NURSES?

Advanced practice registered nurses:

- Are registered nurses with master's, post-master's or doctoral degrees

- Pass national certification exams

- Teach and counsel patients to understand their health problems and what they can do to get better

- Coordinate care and advocate for patients in the complex health system

- Refer patients to physicians and other health care providers

Copyright © 2012 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.