BY: BRIAN YANOFCHICK, M.A., M.B.A.

Are We All on the Same Page?

One of the most important elements defining the mission of Catholic health care is the body of theological reflection we know as Catholic social teaching. We presume thateach leader who becomes a part of this ministry understands and is willing to apply that body of teaching in his or her work. It is foundational for the church's involvement in health care.

It is also important to note that the congruency between foundational values and action on the part of leadership is important to the overall success of an organization.

The Institute for Corporate Productivity research group has identified five "domains" for high-performing business organizations — strategy, leadership, talent, culture and market. In terms of the strategy domain, their research shows that the high-performing organization "is more likely than other companies to say that their philosophies are more consistent with their strategies, and their performance measures mirror their strategies."1

While this organizational research affirms the need for consistency between a company's philosophy and its strategy, CHA research reveals that Catholic health care CEOs, mission leaders and sponsors may hold inconsistent views.

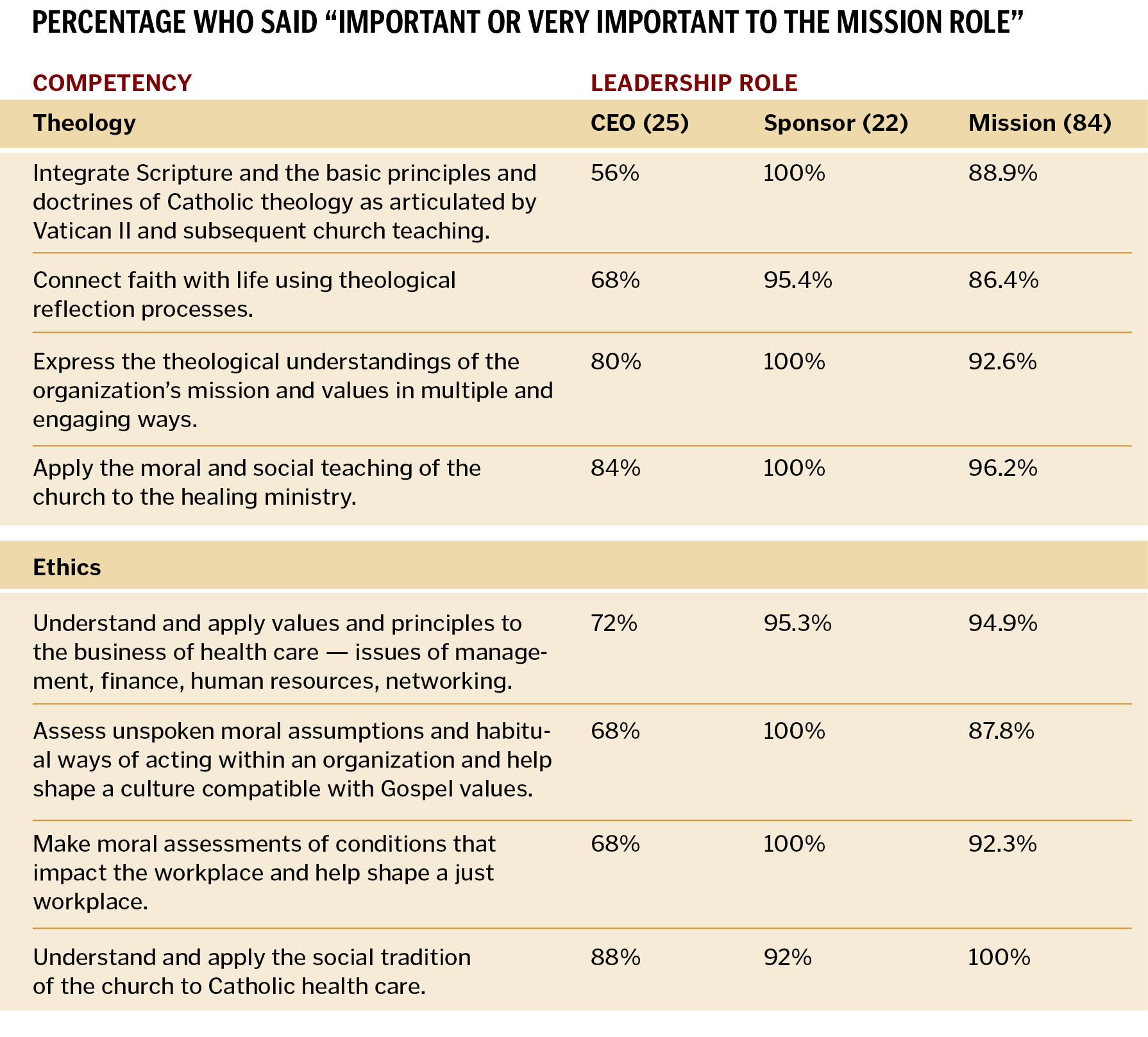

The 2009 CHA survey was part of the revision process for the competency model for mission leadership. It asked leaders to react to specific competencies included in the draft document and to rate them as to their relative importance for an effective mission leader. I was struck by some very important differences in the responses of CEOs compared to those of sponsors and mission leaders, notably in the categories of theology and ethics.

The table on page 79 compares responses from each of these three groups. The numbers in parentheses next to the role indicate the number of respondents. The percentages represent the total of respondents who said a given competency was very important or important.

It is easy to see there are some similarities and some remarkable differences in how these competencies are valued depending on the respondent's role. For example, the responses to "understand and apply the social tradition of the church to Catholic health care" show basic agreement; 88 percent of CEOs, 92 percent of sponsors and 100 percent of mission leaders considered this competency important to the mission role. I interpret these percentages as an indication of "notional" agreement to the importance of Catholic social teaching.

In contrast, responses to "Make moral assessments of conditions that impact the workplace and help shape a just workplace" show only 68 percent of the CEOs saw this as important or very important, versus a range of 92 percent to 100 percent of the sponsors and mission leaders. Do these results mean CEOs generally believe making such moral assessments is not the mission leader's role — in which case, whose role is it? — or do CEOs just consider these assessments unimportant?

This example hints at the possibility of a very real divergence among leadership in the priorities, interpretation and application of Catholic social teaching. Our commitment to the idea of social justice may not carry through to specific applications, even though among the Ethical and Religious Directives, No. 7 outlines some clear expectations regarding the workplace in Catholic health care:

"A Catholic health institution must treat its employees respectfully and justly. This responsibility includes: equal employment opportunities for anyone qualified for the task, irrespective of a person's race, sex, age, national origin, or disability; a workplace that promotes employee participation; a work environment that ensures employee safety and well-being; just compensation and benefits; and recognition of the rights of employees to organize and bargain collectively without prejudice to the common good."2

While the CHA survey results are a bit more than two years old, they are in keeping with what I hear during discussions with many mission leaders. Raising questions about social justice, they indicate, doesn't always receive due attention at the executive or governance table — or it generates resistance.

Some mission leaders attribute this pattern to a lack of in-depth education about Catholic social teaching. Others identify political viewpoints among leaders and board members that sometimes cause them to discount elements of social justice teaching that do not support those viewpoints. Others see evidence that executive leadership and governing boards have not yet acquired the skills needed to wrestle with the very real conflicts that sometimes arise between the values expressed in Catholic social justice teaching and those of the dominant business models that are part of the fabric of our health system operations.

If health care leaders diverge in their level of commitment to Catholic social justice teaching, does it really matter?

It might. Institute for Corporate Productivity research states, "[organizational] culture constitutes the shared values and beliefs that help individuals understand organizational functioning and that provide them with guides for their behavior within the organization. And unless the organization's culture is aligned with its strategy, culture will override all else."3

I don't know of one Catholic health organization that would deny that the values of the Catholic social tradition are part of the philosophy or values of their organization. So, to what extent is this philosophy represented in the organizational strategy? To what extent do our associates see a clear relationship between our stated values and our lived values? To what extent is the culture of our health ministry shaped by the values of the Catholic social tradition and reinforced by behavior modeled by our leaders?

The corporate research suggests that associate engagement and productivity are enhanced when the relationship between culture and strategy is consistent. For Catholic health care, consistency starts with a shared understanding of the key theological and ethical underpinnings of the health ministry, particularly as they are articulated through Catholic social teaching. This requires not only education, but time for reflection to honestly bring to the surface challenges that Catholic social teaching may present to us as individuals and as a group.

To do so generally requires a process of frequent reflection over time, rather than a one-time event. Applying Catholic social teaching in the health ministry is not just about an intellectual understanding of or assent to doctrines. It is about a shared vision for people as part of God's creation and for the communities they form together. It takes time for a group to understand and appropriate something like this.

In his 1991 book, Doing Faithjustice: An Introduction to Catholic Social Thought, Fr. Fred Kammer, SJ, speaks of "graced social structures" that "promote life, enhance human dignity, encourage the development of community, and reinforce caring behavior. Such entities structure or institutionalize good in a way analogous to the good deeds of individuals."4 Sponsors of Catholic health care certainly promote this kind of understanding for their ministries. The collaboration of individuals such as CEOs, mission leaders and others makes it a reality. But a shared understanding and vision must come first. As the book of Proverbs tells us, "without vision, the people perish." (Proverbs 29:18) Perhaps institutional ministries do as well.

CHA has developed resources that may support the efforts of a local health ministry to enter into this important reflection process: "Catholic Social Tradition," a leadership formation module, and "Always With Us: Justice and Catholic Health Care," a new DVD with related print and video material. "Always With Us" is designed to move beyond the basic understanding of the themes of the Catholic social tradition to a deeper application of them in our day-to-day work. Resources such as these could be helpful tools to educate about our justice tradition and address questions that may exist among our leaders.

During an address to Catholic educators during his April 2009 visit to the United States, Pope Benedict XVI said, "A university or school's Catholic identity is not simply a question of the number of Catholic students. It is a question of conviction."

The same insight may be applied to Catholic health care. Our Catholic identity is not measured by the presence of a mission statement on the wall, the number of religious sisters in the system or the number of Catholics on a board or executive team. It is very much defined by the conviction of its leaders and associates that they are called to be one of the "graced social structures" that promotes life and human dignity.

During CHA's annual invitational System Mission Leaders Forum in January 2012, participants will be discussing the challenge of applying Catholic social teaching in a consistent and faithful way within the health care ministry. In preparation for that discussion, I would welcome comments from you on these questions:

- What is your take on the survey responses from CEOs, mission leaders and sponsors?

- What challenges do you experience in your role with regard to the application of Catholic social teaching?

- What approaches have you taken that have allowed for honest dialogue and consensus regarding how this teaching is applied in your setting?

Please send your thoughts to me at [email protected]. I look forward to hearing from you.

BRIAN YANOFCHICK, M.A., M.B.A., is senior director, mission and leadership development, Catholic Health Association, St. Louis.

NOTES

- Institute for Corporate Productivity, "The 2011 Five Domains of High-Performance Organizations" (White Paper, 2011), 2.

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, 5th ed. (Washington, D.C.: 2009).

- Institute for Corporate Productivity, 12.

- Fred Kammer, Doing Faith Justice: An Introduction to Catholic Social Thought, (Paulist Press: New York, 1991): 174.

Copyright © 2011 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.